I’m in an armchair in my dorm’s the sixth floor lounge when I get the call. My mother is dying in her hospital bed in Los Angeles. She’s terminally agitated, trying to stand up and pulling at her IVs. It means her organs are shutting down. Come home, come home now, they say, we’ll try to keep her alive till you get here.

An old friend rushes with me to the airport. On speakerphone in the backseat of a cab — an unusual luxury that I can’t really appreciate at the time — I listen to Zelda,an Episcopal priest at a large, hyper-liberal congregation in Los Angeles, perform last rites. She blesses my mother’s hands, blesses her feet, her wispy hair, her scars, her morphine drip.

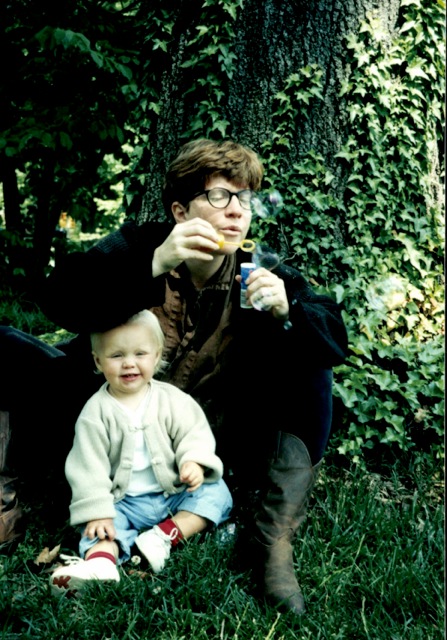

Ruby and her mom

Depart, O soul, out of this world;

In the Name of God the Father Almighty who created you;

In the Name of Jesus Christ who redeemed you;

In the Name of the Holy Spirit who sanctifies you.

May your rest be this day in peace,

and your dwelling place in the Paradise of God.

I love Zelda. I do. Her voice is rich, deep, and unquestionably holy. The prayers she says over my mother are overwhelmingly kind, intelligent, and personal, and I absolutely cannot stand them.

Why the fuck are we talking about Jesus?

I’m pretty sure my mother didn’t believe in God. I’m also pretty sure it’s a sin to swear at a priest, but Zelda just laughs. Thank fucking God for Zelda.

On the five-hour journey westward, I’m pretty terminally agitated myself. I’ve ceded control to this Almighty Passenger Plane and it’s terrifying. I pace the aisle, I loiter with flight attendants who try to be kind but really just want to sit and finish their crosswords. I bother them anyway. I can’t help it.

I’m not ready for this, I tell them. I’m 19, I’m only 19.

This is probably why they stop giving me drinks. I spend the sober leg of the plane ride feeling like some bizarre, reverse version of Schrödinger’s cat — trapped in a box, waiting to see whether or not the world has collapsed around me. I can’t make myself turn on my phone when the plane lands. I don’t want to know if I’ve made it.

Technically, I do make it. She’s alive when I get to the hospital, but sedated. Unconscious. Her face is changeless as I say goodbye, and I know she can’t hear me. Un-reciprocated, my goodbye feels selfish, a polystyrene decoration put up for my own benefit.

We wait. The vigil is longer and duller than I expected. It stretches past midnight, and I change into sweatpants. I buy an overpriced Diet Dr. Pepper and drink it in the hallway underneath a cheerful plastic ficus tree. My little sister falls asleep in the reclining visitor’s chair, which is identical to the one in the next room, and we listen to my mother’s raspy breaths get further and further apart under her oxygen mask. It’s the opposite of counting contractions.

Related

A good 20 minutes pass between my mother’s last breath and the official “time of death” — or better, “time the night nurse came in to turn off the monitors.” Death is fuzzier than any time stamp can capture, and a clock couldn’t have helped me pin down the transition. There is no moment when 21.3 grams of soul pick up and leave the body. So is life over when your heart stops? When you stop breathing? When your brain goes dark? I have no idea how long my mother was aware of her surroundings before the night nurse came in, but I do know she was in the hospital for two and half weeks before she died. I couldn’t talk to her that whole time. I left her for school in August. She was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2009. She was born in 1961. How far back can we stretch that time of death?

Either way, there’s no stretching it forward. After the night nurse leaves, we linger, but eventually we have to start packing up. It’s the only thing to do. We fold the blankets that covered her legs, we pack away the change of clothes she meant to wear home. I Vaseline her wedding ring off her finger, change out of my sweatpants, and pay $6 to leave the hospital parking lot. We strip her and the room of everything personal and abandon them both.

A week later, I’m back at school. It’s the only thing to do. The problem is — as a friend points out, “You’re not crying, I thought there would be more crying” — I’m not a sobbing wreck. I’m not crying at all, and it throws people off. Hell, it throws me off. I’m doing this wrong. I’m not sad, I’ve just become … worse. At everything. School is harder than ever, and all social interaction is fraught. Does this person know? Should they? What do I say on dates? Should I put this on my résumé? Should I wear a sign? Am I overanalyzing? Why is it impossible to grieve here?

There is a grouchy line from the nonbiblical “Book of Daniel” that touches on this problem with grieving too perfectly to pass up: “There are no decent settings for joy or suffering. All our environments are wrong. They embarrass our emotions. They make our emotions into the plastic tiger lilies in the window boxes of Howard Johnson’s restaurants.”

I think some of the modern difficulty with death and grieving comes from impersonal dwelling places, from this Howard Johnson’s sanitized sameness. How can I miss my mother in a room she never walked in? In a space that won’t be mine in a few months? In a community where only one or two people even know her name?

A college dorm room is an embarrassing place for grief. In the same way, the sixth-floor lounge was the wrong place to find out that my mother was dying; the back of a New York cab was the wrong place to hear her final blessings; and that hospital room, with its ersatz ficus and requisite faux-leather recliner, was the wrong place for her to die. Hell, the computer lab I’m sitting in is the wrong place to be writing this. None of these spaces are emotionally big enough to hold the full impact of loss. They make you feel false and silly right along with the plants.

In mid-winter, I’m tramping across Central Park, late to something or other. I’m freezing, stomping on ice, and massively angry — when something in my brain flips. I’m no longer angry, I’m tearing up — and being able to walk and cry quietly, even in this very public place — is perfect.

The raw, communal anonymity of New York streets is perfect for grief. I’ve cried on the subway, in airport security, in line at the post office, in churches, in elevators, and in my car headed north on the Hollywood 101 freeway. None of these are really “places,” and that’s the trick. They’re waiting places. They’re inter-places. When I’m in transit, when I’ve ceded control of my time, when I’m moving from one wrong environment to the next, I’m able to experience a piece of this loss that is just too large to feel anywhere else.

Grief is a kind of inter-space too — an unsettling state of transition between presence and un-presence, between being a have and being a have-not. Transition is hard. It’s stressful. It’s uncertain.

Still, it feels so good to be moving.

Ruby a student at Barnard College studying American Studies. If you want to hire her or have any good book recommendations, you can reach her at rdd2122@barnard.edu.

A version of this article was originally published in The Eye magazine of the Columbia Daily Spectator.