Six weeks before his fatal motorcycle accident, I saw my ex-boyfriend Jason for the last time. He visited me in Brooklyn and slept in my bed. We drank too much wine and blew pot smoke out my bedroom window, like teenagers. We talked about the life we’d lived together in New Mexico, a few years before, while I wrote my first novel.

“I think about moving back there all the time,” he told me. “We could live in the desert again.”

But I didn’t want to move back with him. For years I’d been hooked on Jason like I was an addict and he was my drug, but when I saw him that summer he was so manic and volatile that I decided it was finally time to move on with my life, and let him move on with his. At the end of the week, Jason flew home to Arkansas and I stopped answering his texts and calls. When the frequency of the calls increased in late July, I reluctantly answered: It was Jason’s brother, informing me of the accident.

His funeral was in Little Rock. Once there, I became “the New Mexico girlfriend.”

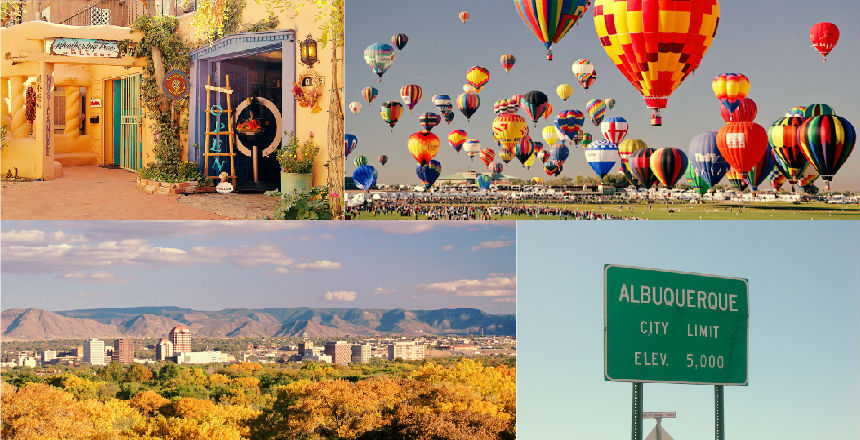

A TV mounted to the wall of the funeral parlor played a slideshow of photos, including one I’d taken of Jason giving me the thumbs up at the Albuquerque hot air balloon festival. Every time it appeared in the rotation, I remembered sitting in the damp dawn grass, how we’d watched the balloons launch and he’d said, “Someday I’m going to marry you to death.” Part joke, part threat, part promise. I preferred watching the slideshow on repeat to looking at his body laid out in the coffin.

Related

In the months that followed his death, I became obsessed with going back to New Mexico, and spent insomnia-fueled nights browsing Craigslist ads for property listings. I found a miner’s cabin for sale on the Turquoise Trail, a 1991 Spirit Mobile Home in Pojoaque, a three-bedroom in Moriarty for less than $50,000. My favorite part of each listing was always the property photos because they showed the high blue sky. When I dreamed of leaving, I never thought about quitting my job or what I’d tell my family. I thought of the sky alone and it made me break out in yearning like a rash.

For years I imagined what it would be like to go back but fear prevented me from making a move. I was afraid of the strength of my own desire. What if I got all the way out there, stood under the banner of that sky, and felt nothing? What if that land was, just as my relationship with Jason had been, more beautiful in memory than in real life?

New Mexico’s state nickname is the Land of Enchantment. The one-bedroom apartment Jason and I shared in Albuquerque had a view of the Sandia Mountains, which glowed pink at dawn and dusk. We rode his motorcycle late at night up Tramway to see the lights from the big houses in the foothills sparkle. We stood in petrified lava fields and rolled down white sand dunes and tore hot sopaipillas open with our bare hands before dipping them in honey.

We also fought. More than once, Jason pulled over to the side of the highway and threatened to leave me there. He slapped me in Wal-Mart, and told me we could only be together if I took anti-depressants to stabilize my moods. Why did I stay with him? The easiest answer is: I was bewitched. His charm cast a spell. The land was enchanted.

When Jason died, I found myself in another enchanted land. Grief made the ordinary breadcrumbs of my days seem like signs I could follow, along a trail leading me back to him. I listened to music played in coffee houses and sometimes felt certain he was curating the songs. He met me in my dreams, but the clasp of our hands never held. Outside a bar in Key West, I stopped on the sidewalk and listened to a band play the bluegrass song I’d last heard at his funeral. What did it signify?

With Jason there had always been signs: Signs that we should be together, signs that we should stay apart, signs that staying apart would never work and that in the end I would always be tied to him, for better or worse. When I finally flew back to Albuquerque last April, three years after his death, I anticipated these signs might come in the form of dreams, or billboards, or feelings I got in the places we used to visit together. I thought I would feel him with me.

But there were no signs of Jason in New Mexico.

There were no feelings I hadn’t felt before, no landmarks I hadn’t already revisited a thousand times in my mind. The scraggly brush and dry arroyos along I-25 were exactly where I left them. The casinos with their adobe façades—still there. And the sopaipillas at the Plaza Café were just as hot and chewy as I remembered. I had been afraid of not feeling enough, but really, what better place to be unleashed from my grief? I didn’t need to drive by our old apartment, or any other place that memorialized what was over and gone. No one was watching, to see if I was sufficiently moved by the experience of my return. I felt like the land had welcomed me back, no questions asked.

In my rental car with the windows rolled down, sun on my arms, I stopped haunting myself. I didn’t need to search for signs that would tell me what I already knew: New Mexico had once been ours; now it was mine.

Leigh Stein is the author of the novel “The Fallback Plan,” a book of poems, “Dispatch from the Future,” and “Land of Enchantment,” a memoir forthcoming from Blue Rider Press in 2016. She is also the creator of BinderCon, a professional development conference for women and gender non-conforming writers. Follow her @rhymeswithbee.