Peruvian football players (Wikimedia Commons)

Peru is known for Machu Picchu and, especially in recent years, for its astonishingly good food. What it’s not known for, though, is soccer. In a region of soccer powerhouses like Brazil and Argentina, Peru has for decades been one of the worst teams in Latin America.

Our home team hadn’t played in a World Cup in 36 years. But this year, miracle of miracles, it’s back in the game —competing in the global once-every-four-year soccer tournament.

I grew up inheriting the love for the game from my mother, especially for the national team, despite its failings. In Peru, gender roles in sports are clearly defined: Girls play volleyball, boys soccer. When I was about 11 years old, after much nagging, my mom took me to the mall and bought me a pair of soccer cleats. “I want her to be able to do what I wasn’t allowed,” she responded to those who asked if she was ok with me becoming a soccer fan, and even, gasp, playing the game. While she was growing up, she had dreamed of going to the stadium to watch either the national team play or Universitario de Deportes, another team she rooted for. “It’s no place for girls,” her brother would say. It wasn’t until 2003, when she was 45 years old, that she went to a stadium for the first time, to see Peru play against Brazil. She knew every chant by heart.

Her support for the national team, affectionately known as la Blanquirroja, would at times seem like an obsession. She’d arrange her schedule around for game days, careful not miss a minute of play.

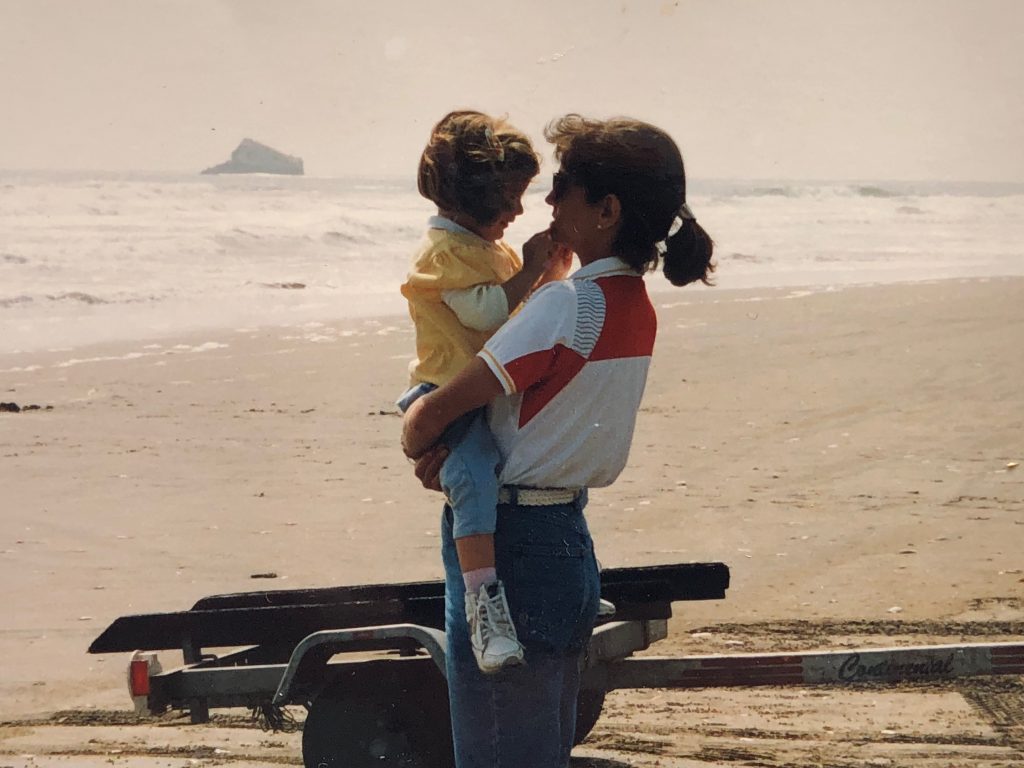

Fe and her mom (Courtesy of Fe Martinez)

After I moved to New York for grad school, we would FaceTime during halftime and after the game to cheer or commiserate. We loved other things, too, other sports. But nothing surpassed the love for soccer. So it’s not surprising that la Blanquirroja was with us when my mother moved to New York to fight a very rare and aggressive form of lung cancer. What was different is that, for the first time in my life, our team was actually playing well! The possibility of playing in the World Cup was no longer “mathematically impossible.” It was real. As real as the possibility of losing my best game-mate.

In early September, Peru beat Ecuador in Quito, for the first time in our soccer history. It was also the same week my mother was urgently admitted to the hospital after the cancer spread to her spine, rendering her unable to walk. A few weeks later, in October, Peru tied against Colombia, leaving us two games away from the coveted spot. My mother and I were at a physical rehab facility in New Jersey, both of us in her bed watching the game on my phone. The nurses came to check if we were ok when we started screaming after Guerrero, our team captain, whose name in English very aptly means “fighter,” scored with a few minutes left. For the game that would decide our World Cup fate, the moment we’d been waiting and hoping for, forever, she was back at the hospital.

As we waited for the game we’d never imagined would come, the doctors had already given us the final verdict. The day of the match, on November 16, mom was somewhat lucid and even aware of its importance. I saw her, bundled up in a cold hospital room, a shell of herself. She looked like someone else but there were these sudden and small glints of happiness in her eyes, even some excitement about the upcoming game. She tried to stay up, but couldn’t. I stayed by her side, naively waiting for her to wake up, wanting to shake her up to watch the game together.

A young Fe with her mom (Courtesy of Fe Martinez)

I walked into her room the next day, relieved to see she was still with us. I told her, barely able to breathe, “Ma, we did it. We’re going to the World Cup.” “I knew my cholitos* would make it,” she said with a big smile, using a popular Peruvian term of endearment. I was even able to show her the goal that clinched their spot. She passed away a week later

A few months later, on a rollercoaster of grief, I found myself in New Jersey again wearing the Peruvian team jersey. This time I wasn’t headed to a rehab facility. I was rushing to get to the stadium where Peru was playing Iceland in a friendly match — one of our last games before the World Cup. En route, I had a moment of sensory overload, I was transported back home; Peruvian flags everywhere, the faint sizzle of anticuchos being grilled, and never-ending lines of Inca Kolas (Peru’s famous neon yellow soda) everywhere I looked.

Inside the stadium, I reached for my phone and start typing, “Ma, I got last-minute tickets!” Her phone number, of course, had been disconnected for weeks. It was one of the many things that ended up on my list of to-dos after she died. I froze on the spot as my throat choked up and everything became blurry. I was ready to leave and take the next train home. But, this was bigger than me.

I knew my mom would want me there cheering, not hurrying back home crying in a train full of strangers. Soccer, for us, was so much more than the game; it was a forever promise, an unspoken agreement of spending time together, sharing dreams, cursing disappointments and screaming with joy. It was something through which my mom showed me I could do what I set my mind to, regardless of what others said. With the World Cup underway and levels of excitement through the roof, it’s impossible not to feel a pang of sadness and longing. But also hope. Hope that somewhere, my mom is watching and cheering along with me.

Fe Martinez studied media and communications in Lima, Peru and New York, and is passionate about exploring different storytelling mediums. She lives in New York, where she watches more TV shows than she should and spends an embarrassing amount of time chasing after her dog in the park. You can follow her on Twitter at @mfmartinez.

Listen to Fe share her story in Spanish on NPR’s Radio Ambulante. An English translation of the transcript is here.