When Samuel G. Freedman’s book Who She Was: My Search for My Mother’s Life was published 20 years ago, it got lost during the literary season that also included the family dramas authored by Joan Didion, Joseph Lelyveld, and Stephen V. Roberts. Over the intervening decades, Who She Was languished in relative obscurity before going out of print.

But Freedman had always felt that Who She Was was not only his most personal book but his most artfully written. And so on the 20th anniversary of its publication — and not long after the centennial of his mother’s birth — the book has been re-issued by The Sager Group with a new introduction by Kelly McMasters. Here is an excerpt, drawn from the book’s prologue.

On a windswept, darkening afternoon in December 2000, I brushed the snow away from the marker of my mother’s grave. With each sweep of my gloved hand, the raised lettering of the simple plaque gradually became visible, showing her name, ELEANOR FREEDMAN, and the inscription our family had chosen: A SPECIAL PERSON. It had taken me some time to find the marker, even with a map from the cemetery office and a computer printout designating the exact location like the block-and- lot number in a suburban subdivision. I had not visited the grave in twenty-six years, since another December afternoon, when my family buried her.

I could still see, after so many years, the tears sliding out of my father’s unblinking eyes. I could still hear my sister’s howls of grief. But my memories of my mother herself had grown vaguer and less distinct over time. I could not remember the timbre of her voice or the pattern of her inflections. I could not summon her face without a photograph. What I did recall in all its shameful detail was the only visit she made to me at college, and my command that she sit rows apart from me in my classes, that we pretend to be strangers until we were safely blocks away from the classroom building. I was just eighteen then, two months into my freshman year a thousand miles from home, and in the full thrall of this new independence. She was already dying of cancer, pulling me back in love and obligation to the excruciating spectacle of her demise. From that day until this one, my memory of her illness, of our family’s deathwatch, had eclipsed all the other memories of her existence.

Now I was forty-five, the same age my mother had been when a doctor found that first lump in her breast. I was only five years younger than she had been at her death. I was more than a decade into my marriage, as she had been in hers. I was the father of two children who looked at me, as I had looked at her, only as a parent, not someone with a whole autonomous life, most of which had preceded their arrival. And, as if my own wish during college were taking revenge on me, I had discovered that my mother was more and more a stranger to me. Besides having been my mother, besides having been my father’s wife, besides having been someone who died miserably and died young, I did not know who she was.

In the quarter century since our family had interred her ashes, I had become my father’s son, by choice and by default. My stepmother had been part of our family, and my life, for more years than my mother was. I had not even gone to the cemetery this bleak afternoon with the intent of visiting her grave. I was there instead for the burial of my father’s sister Clara, a devoted anarchist from childhood until her dying day. On her part of the family tree, the Freedman part, lives were lived in bold political engagement. My grandfather and namesake had been sentenced to death as a teenaged radical in Poland; he fled from prison to England during a workers’ uprising and bought a steerage ticket to America on a ship called the Titanic before deciding to sell it to a friend. Out in the Jersey farmlands, he raised his children in an anarchist colony with its own experimental school, and every year I attended the reunion, soaking up the tales of strikes, May Day parades, and Woody Guthrie concerts. That my grandfather Samuel died fourteen years before my own birth made him only more vivid, nearly mythological, in my imagination.

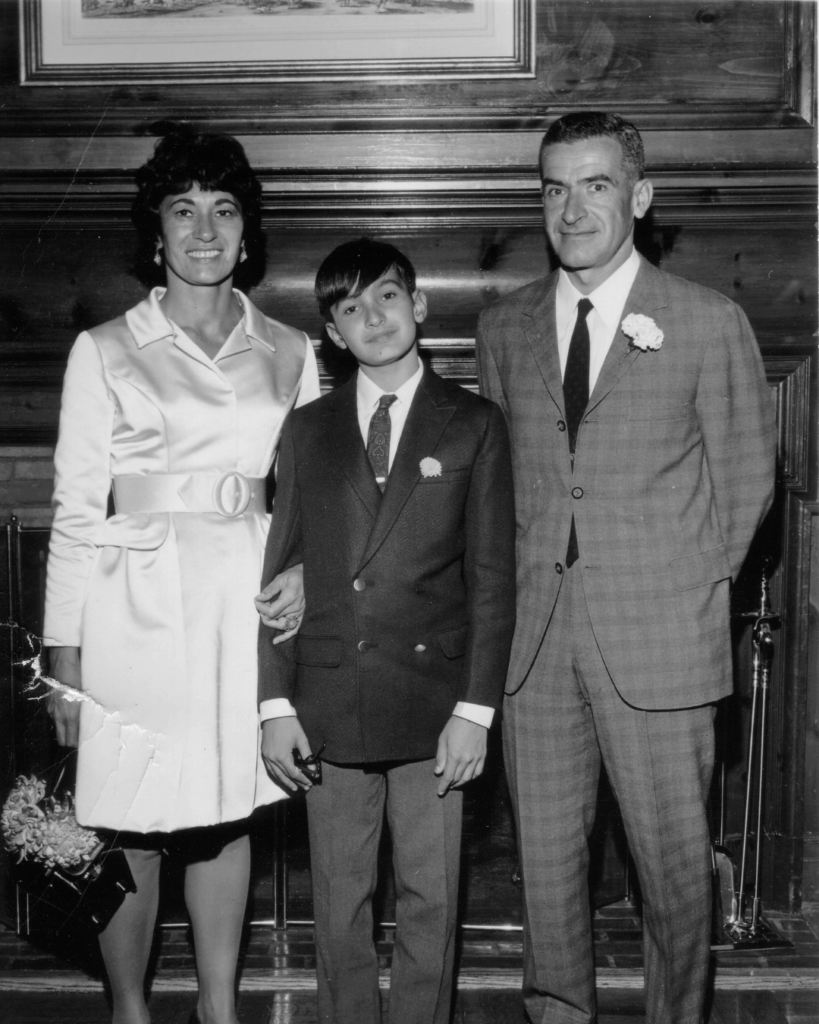

The author with his parents at his bar mitzvah (October, 1968)

My mother’s people, the Hatkins, formed the conventional part of the family tree, the scufflers and schleppers in an East Bronx walk-up, relieved to make the rent every month. Fluent only in Yiddish, and disinclined to wear her hearing aid, my grandmother Rose had proven an impenetrable figure during my childhood. Sol, my grandfather, fussed and doted too much; my strongest memory of him was a day when I was eight or nine and he took me sledding, and kept insisting I rest between plunges down the hill. Years later, as a journalist, I had chanced upon a word to describe the whole clan, a bit of black slang, of all things. Drylongso was the term, meaning something that has been left dry for so long it is now ordinary as dust.

An odd thing had happened, though, during the previous few months. In conversations and occasional speeches, I found myself mentioning stray details from my mother’s life—her pride when Bess Myerson was the first Jew chosen as Miss America, her dancing in the streets when the United Nations voted statehood for Israel. I wasn’t even aware at first of how often I was telling these stories until an old friend pointed it out. “I’ve known you twenty years,” he said one night. “This is the first time I’ve ever heard you talk about your mother.” His words jolted me. I had to ponder what my reflex to speak of her meant. I carried that mystery with me from place to place over the weeks, and eventually I came to an answer. I realized that, at last, I wanted to discover my mother’s life. I wanted, almost literally, to claw at that frozen cemetery ground, to exhume the soil flecked with her residue, and from it to conjure the past.

The only way I could rationalize my mother’s death at fifty, the only way I could make it bearable, was to transform it into some kind of precondition for my own adulthood, as if her coffin were my chrysalis.

She and I had been complicit in the sin of forgetting. For my part, I had built an identity on the rejection of my mother, on the imperative of denying all the softness in myself. On my first day of kindergarten, a block short of the schoolyard, I had ordered my mother to turn around and let me arrive alone. I spent an hour getting home that day, crossing the same few streets again and again, delirious in my show of autonomy. A straight line ran from that day to the day at college. The same straight line ran through every day when I so easily could have visited the grave and never did. The only way I could rationalize my mother’s death at fifty, the only way I could make it bearable, was to transform it into some kind of precondition for my own adulthood, as if her coffin were my chrysalis.

My mother died three weeks before I was hired for my first job as a professional journalist, interning on a small daily newspaper. In what would become my career, I learned first how to report events I had witnessed or that had occurred only hours or days before, the robberies and ball games and Board of Ed meetings. Gradually, over decades, I taught myself the kind of research a historian practices, the method of recapturing vanished times and remote lives. I had utilized those skills to write about other families in other books. Now, shivering in the cemetery’s December twilight, fingers and toes going numb, I decided to apply them to my own flesh and blood.

As I beheld her grave in December 2000, I wanted so fiercely to know who else she had been. I wanted to know about the family and the home and the neighborhood and the world in which she had grown. What did it mean to have come of age during the Depression, World War II, the Holocaust? I no longer could settle for the routine answers — We were poor, but everybody was poor. … Bubbe lost her whole family. What did those giant forces, forces that shook a planet, mean to my own mother? How did they shape her, or misshape her? I harbored no desire for cheap sentimentality or easy solace, but neither did I seek a bill of indictment, a lurid litany of dysfunction. The questions that seized me were of a more quotidian sort. Who was my mother before she became my mother? Whom did she love? Who broke her heart? What lifted her dreams? What crushed her spirit? What did she want to be? And did she ever get to be it in her brief time on earth?

My mother should have lived long enough to write her own story, the story she was groping toward in those yellowing pages I had discovered in the storage area. She was smart enough. She was skilled enough. She was young enough, young enough that she still should have been alive now, a graying grandmother in her late seventies, taking literature courses at Elderhostel. The duty never should have fallen to me, and yet I welcomed it, having failed in so many other filial duties. After all my years of rejecting her in life, after all my years of posthumous neglect, I finally had found the means of penance.

As dusk settled over the cemetery, I picked my way between the headstones and back toward the mourners still at Aunt Clara’s grave. It was time to leave. It was time to pick up the tools of my craft, the pens and notebooks, the telephone and computer. I thought of them now as an archaeologist’s instruments, as if I were scraping up the dirt of antiquity one spoonful at a time and sifting it through wire mesh to find what chip of pottery or fragment of bone might remain. As I collected the pieces and tried to assemble the skeleton, I told myself I wanted only one thing: to see my mother clear and true.

Samuel G. Freedman is an award-winning author, former columnist for The New York Times, and professor at Columbia Journalism School.