I would tell her I’m dating the “Man of My Dreams,” then laugh at myself right along with her for sounding so damn cheesy.

I would smell her.

I would organize a movie marathon featuring “Adventures In Babysitting,” “Groundhog Day,” “The Lion King,” “A Far Off Place,” and “The Man In The Moon.”

I would cook steak au poivre and a quatre quarts, then indulge with her until painfully stuffed.

I would use the “good” silverware every day.

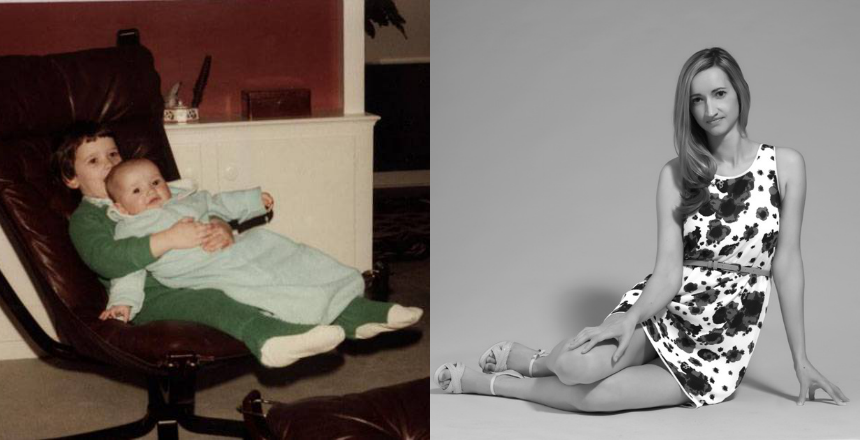

I would remind her about the time, shortly after moving from Illinois to Connecticut, when we decided to stop fighting and start being friends.

I would ask her how cold she really was on the December days she insisted on wearing shorts to school in defiance of being uprooted from Illinois, where the winters were (relatively, I suppose) much harsher.

I would reminisce with her about Fred, her barely-operative gray Toyota Tercel, and how we used to blast Cat Stevens from within it.

I would express gratitude for all the grammar nagging, now that I’m a writer.

I would make jokes about our parents only she and I could appreciate.

I would tell her how sad it makes me that Dad no longer mistakes me for her over the phone, because process of elimination isn’t necessary to determine which daughter’s calling.

I would refrain from sneering at her bubblegum nail polish and mostly pink wardrobe.

I would apologize for screaming in her ears on every occasion they were infected while we were little.

I would emphasize that I’m aware of my capacity to be an asshole, and that I don’t consider her weaker for being more sensitive.

I would confess that her hypochondria upset me more than I ever let on — especially the time she convinced our little brother that she was HIV-positive (she wasn’t) over the course of a three-hour phone call.

I would forgive her cokehead ex-boyfriend, Max, for lying about losing his train ticket so I would loan him twenty bucks, which he most certainly spent on crack.

I would remind her that the kids she babysat and the students she taught throughout her life adored her.

I would mention that even the friends and colleagues she’d alienated showed up to her funeral.

I would tell her how close our little brother and I have become since her alcoholism first took root, because nobody else could possibly understand what she put us through.

I would report how both he and I experienced an overwhelming, albeit temporary, sense of spirituality just as she passed, on Sunday, April 5, 2009.

I would tell her I found the one journal entry she penned during a psych ward stay while rummaging through her effects on the day after her death.

I would describe the weird, out-of-body type dreams I’ve had since she left us.

I would explain that people are remarkably nice to you right after your sister dies, but that the special treatment eventually dwindles — because life goes on.

I would describe the awkward, nervous way I laugh whenever I feel obligated to explain that my older sister succumbed to cirrhosis at age 30 a few years back.

I would hug her tightly, without wondering why.

I would shout, “I love you” without a shred of embarrassment, at any and all times.

I would laugh.

I would cry.

I would start believing in God, because reincarnation requires a miracle.

Mélanie Berliet, a New York City-based writer, is the author of “Surviving In Spirit: A Memoir about Sisterhood and Addiction.” Her work has appeared in Vanity Fair, Elle, Cosmopolitan, The Atlantic, New York Magazine, New York Observer, Esquire and McSweeney’s, among other publications. She likes knee-high tube socks, acrostic poetry, her brother, and the color navy blue.