I was the late bloomer in my friend group in many respects: protective and cautious immigrant parents meant that I had the earliest high school curfew (by a couple of hours) of all of my friends, and the amount of time it took for me to come out to myself meant that I was the last to have a first kiss and romantic relationship. But among that very same group of friends, I was first in line for the life experience no one anticipates having at 23 – losing a parent.

The summer between my two years of graduate school, my father went from being in seemingly perfect health to dead in the course of two-and-a-half weeks. When my father entered the hospital, my mother and I thought that we were dealing with a chronic illness or long-term hospital stay — never dreaming (or reading between the doctors’ lines) that the end was so near. But it turned out that a form of pulmonary fibrosis, most likely due to asbestos exposure in childhood, had ravaged his lungs, remaining hidden until it was too late for any treatment or intervention to make a difference.

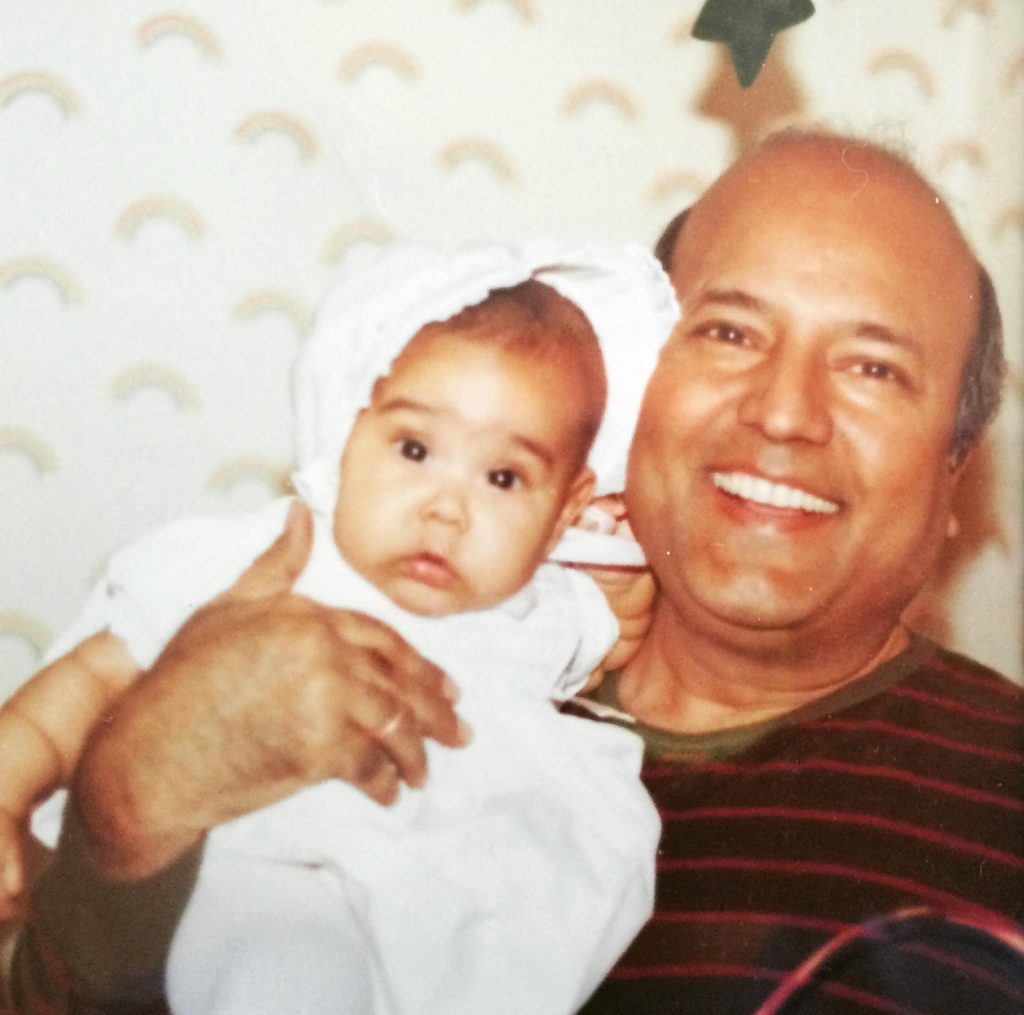

Baby Nishta with her dad (Courtesy of Nishta J. Mehra)

And so I was the first one: the first to place a DNR, to watch my parent die, to drive my other parent home afterward, to plan a funeral, to write my father’s obituary, to deliver a eulogy, to pick an urn. To help my mom navigate the maze of phone calls and paperwork that followed, to learn that she and I would grieve the very same person in very different ways — so different, in fact, that it complicated and permanently changed our dynamic. I was the first to figure out that most people had no idea what to do with or for me in the face of my grief.

I was lucky at that time to have access to affordable counseling services through my student health center, and the counselor I saw there connected me with a young woman named Annie who had started a group for students who had recently lost a parent. Each Sunday, Annie invited us into her home for a potluck brunch, gently guiding us into a conversation where we could say the things we couldn’t say to anyone else in our lives. We shared the strange coping mechanisms we were cycling through. (Mine at the time involved popcorn, M&Ms, and binge-watching episodes of “Sex & the City” on DVD.) We admitted our frustration, despair, and blind anger when faced with the outside world, and offered each other witness. Occasionally Annie read a poem or quotation to close the meeting.

Those meetings walked me safely through those earliest, most treacherous months of fresh grief; they allowed me to finish out the year and earn my masters. I don’t remember much else about that time period, but I’ll never forget Annie.

‘As my grief moves through its teenage years … to be trip-wired back into the space of fresh loss feels like a gift, a reminder of grief’s power.’

At 36, I am nearly 13 years away from my father’s death, but the grief of others is much closer inside my own experience: Rebecca and Courtney, whose mothers died from cancer; Dave, whose sister died in the earthquake in Haiti in 2010, and several students and colleagues with parents or spouses gone. Welcome to the club no one wants to join, I find myself saying time and again, writing long emails, copying out poems, showing up at funerals, and making myself available for empathizing and advice. You may want to stay off of social media on Mother’s/Father’s Day; buy cheap plates at Goodwill and find a safe place to throw them; ask your best friend to serve as information hub so that people go through them instead of you; don’t skip your flu shot this year, because your immune system is going to be run down for a while.

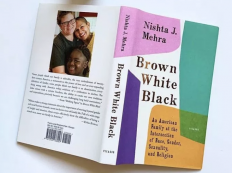

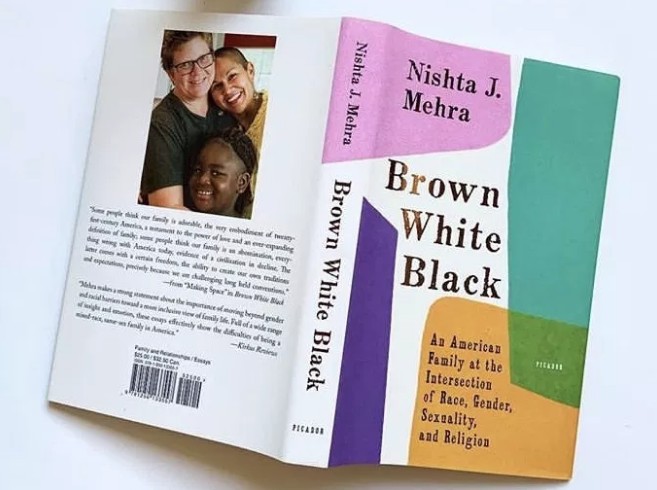

The author is out with the new memoir “Brown White Black.” (Courtesy of nishtajmehra.com)

As my unwitting expertise becomes more and more relevant — none of our parents, after all, are getting any younger — my friend Courtney has dubbed me the “grief doula.” A doula is, of course, a woman trained to assist another woman during childbirth; she is not physically involved in the delivery, but instead stands with and advises the woman giving birth, advocating for her and serving as her spokesperson when necessary. She stands in service of the one doing the physical and emotional labor of birthing since she cannot, even if she wanted to, take on the work of delivery herself.

Birth and death are the bookending parentheses of our human experience, imbued with an overarching sense of the sacred, rendering us physically exhausted and emotionally vulnerable. As a culture, we pay more attention to the beginning of life than to its end, but losing someone changes you in equally dramatic ways as welcoming someone into the world. The work of offering to walk with others through the strange minefield of grief is work I never anticipated doing, an expertise I unwittingly acquired, but it is work I feel viscerally called to do.

Though I never would have chosen the term “doula” for myself, I find it fitting. Not every grieving person needs the same set of things; they may not even know what they need until someone else suggests it for them. As a grief doula, I stand at the ready: ready to interpret complicated paperwork, to advise the spouse and friends of the griever, to give the griever permission to draw boundaries as needed, to pay attention to their grief when most everyone else’s attention and concern has trailed off already.

Due to the nature of the work, doulas are granted audience to some of the most beautiful and wrenching moments imaginable; I hold mine like treasure. Watching others walk through grief sometimes triggers intense deja vu, but I have learned to embrace this experience instead of resisting it. As my grief moves through its teenage years, I see the ways I have managed to contain and limit it; to be trip-wired back into the space of fresh loss feels like a gift, a reminder of grief’s power.

Almost everyone who loses someone reports feeling a sense of urgency in the wake of that loss, a kind of clarity regarding what ultimately matters, and desire to hold onto this new way of seeing. Standing inside the grief of others has had the unanticipated impact of allowing me to keep this promise to myself, to push past the daily to-do list and small talk and peel back the layers of acceptable public persona and offer myself in earnest service to another.

Nishta J. Mehra was raised among a tight-knit network of Indian immigrants in Memphis, Tennessee. An English teacher with over a decade of experience in middle and high school classrooms, she lives with her wife, Jill, and their six-year-old, Shiv, in Phoenix. She is the author of two essay collections: “The Pomegranate King,” published in 2013, and “Brown White Black,” now out from Picador; connect with her via her website, nishtajmehra.com, or on Twitter and Instagram @nishtajmehra.