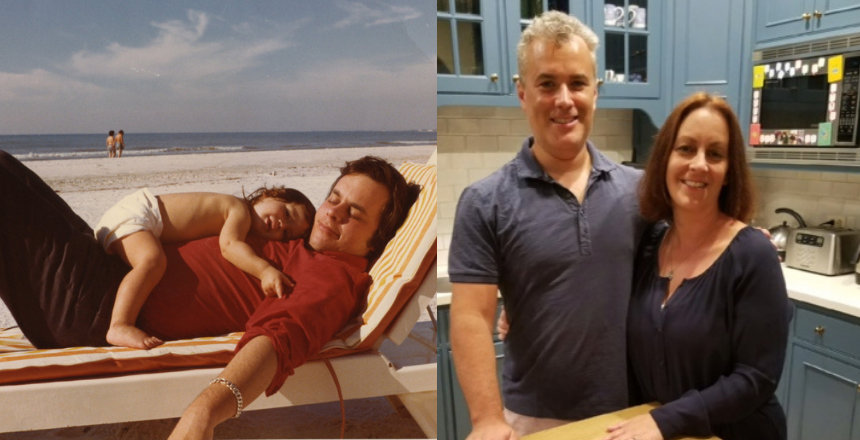

Rachel with her dad, Jeff Zients, on the beach; Rachel and her cousin, Jeff Zients, in 2016

Jeff Zients is the new White House Coronavirus Response Coordinator under President Biden. Jeff Zients was also my father.

Not this Jeff Zients. My Jeff Zients died in 1975 when I was four. This Jeff Zients is my second cousin, one who admittedly I don’t know that well. In fact, I didn’t even know there was another Jeff Zients until I was an adult. He has always been kind to me the few times we have met. A brunch here. A visit there. Our grandparents were siblings, but we didn’t grow up together. To me, the name Jeff Zients has always meant loss and sadness, a what could have been. And now his name is everywhere, redefining that meaning. It’s been — a bit weird.

Zients supposedly means rabbit in Russian. Trying to avoid conscription in the Czar’s army, a false name was given when authorities knocked at the door because a rabbit hopped by at the same moment. This simple cleverness gave them time to escape. I have no idea if this tale is true and the spelling of our name has been changed over the years so it is hard to check. I choose to believe it because I love the image of a rabbit hopping away towards something safer and better.

But when I married I took my husband’s name, mostly because I wanted to be a single unit referred to all together as a family. But I just couldn’t shake Zients. And so it became my second middle name. I gave the name to my sons as well. This name, in lieu of years of memories, connects me to my father, grief and all. I couldn’t let it go.

It doesn’t escape me how strange it is that the same name that brought me so much pain is now leading the charge to try to stem off more pain for us as a nation under the direction of a president who has never shied away from his own grief. It is not for me to cast President Biden as the grief president, but as someone whose life has been dominated by grief, I now see myself in his own experience.

It doesn’t escape me how strange it is that the same name that brought me so much pain is now leading the charge to try to stem off more pain for us as a nation under the direction of a president who has never shied away from his own grief.

When my father died in 1975, grief was something people didn’t talk about very openly. Add that it was a suicide, and the barriers went up even more. But I have always led with my grief. I didn’t know grief wasn’t to be shared or shown. I credit my mother with that. She even wrote a children’s book about parent loss with me as the main character, the literal poster child for grief. I am Rachel. My dad died when I was four. That’s what you need to know about me and I need to get that information out to you quickly so you can understand me and not judge me for my apparent wounds, perhaps get to know the whole me. The whole me includes the missing parts of me.

President Biden has also led with his grief. His early loss of his wife and infant daughter and his recent loss of his adult son have guided how he operates in this world. We are being led now by a man who understands that we want to be asked about those we are missing; who recognizes it is something that stays with you, shapes you, changes you. He is setting a tone for healing and simultaneously acknowledging how hard life can be sometimes.

As he said at the inauguration, “Because here’s the thing about life, there’s no accounting for what fate will deal you.”

Whatever side of the political aisle we are on, we have all had loss this year. We are all grieving — a sense of normalcy for our children, community, friends.

Half a million fellow citizens.

For me, President Biden is establishing an environment where loss and grief are not to be mocked or swept under the rug, as if to mourn openly is to admit some kind of weakness, when rather it signifies strength.

As a writer, I am always looking for story or connections, something to tie everything together and to provide meaning. It would be too easy to say my father is no longer alive but his name lives on in the work this president is doing. But that isn’t it, because my father isn’t alive and this Jeff Zients is his own person. And this is bigger than the small coincidence of two men from the same family with the same name.

This is grief taking center stage.

This is now a memorial on the National Mall for all.

This is now a president who isn’t afraid to show his emotions and his complexities in managing them.

This is now permission for feeling our collective losses.

This past year was filled with so much loss, I almost couldn’t confront it. And now I feel not only that I can, but that I should. I mean one day in March last year, we just all went inside and had to adapt to a brand new way to make our way through.

At times throughout my life, I fear I made people uncomfortable with my remembering, a walking embodiment of what you don’t talk about. It was hard not to have my identity wrapped up in that pain. But I had to do all of that, wear it around for awhile, so that I could put it away eventually. And I feel that is what this administration is allowing us as a nation to do now. Permission to grieve.

As Biden said, “To heal we must remember.”

I can now talk about my father without it being all of who I am. I can now see my cousin’s name in the paper without my stomach dropping. In fact, I actually see the beauty in the coincidence and the gift of the grief that has colored my life. I find it comforting, like a wink from the universe, carrying me along with a little nudge of “look how far you’ve come.”

It is so ridiculously on the nose, how can I not try to make meaning out of it? I mean once upon a time my family came to America to escape conscription in the Czar’s army and now a Zients is being referred to as the Covid Czar trying to help save America. It’s kind of an epic tale. So let’s talk about what we have lost. Let’s remember. Let’s stop pretending this hasn’t been a painful time for so many. That is what the grieving process can give us – a reminder of our own survival as we carry on.

Rachel Zients Schinderman‘s work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, The Manifest Station, and Shondaland, among other publications.