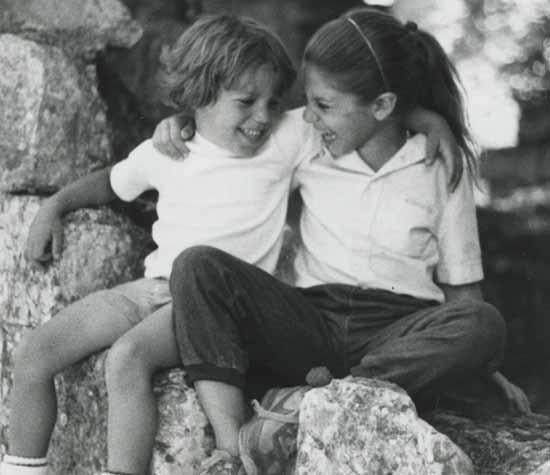

I sometimes think about the last time that I saw my brother Jed alive. He had just dropped me off at my apartment on West 110th Street, and was pulling away in his truck, waving a hand out the window as The Dave Mathews Band blasted from the CD player. (It was 1998.)

The memory is of sunshine and warmth, although that couldn’t be true, since it was December in New York City. I remember standing outside of my building for a moment, happy that we had run into one another.

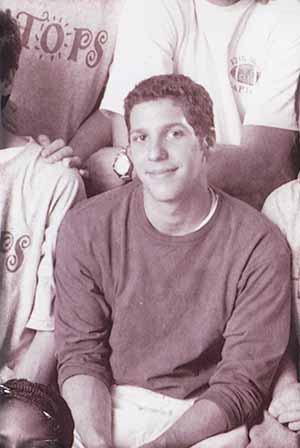

It was such a classic scene — the music, the cigarette stubs in the ashtray, his embarrassingly huge Range Rover. He was the epitome of a coddled, carefree college kid home for winter break, joyriding around the city.

One week later, I was again standing outside my apartment building. This time, everyone in my family was there, except for Jed. That day we were driving — hurtling, really — toward the place where the police had said (quite casually, to my mother, on the telephone), that Jed had hanged himself. And I don’t recall it being warm.

Ostensibly, he did it because of his girlfriend. I know that sounds almost comically typical. You wouldn’t even write that into a movie plot, it is so overplayed. Yet it’s the truth. At 20 years old, Jed was impulsive, dramatic and too young to understand the permanence of his decision. Probably ill, although he was never diagnosed, he was unable to see past his driving necessity to prove his love for her.

Of course there was the utter confusion and shock following his death. My parents retreated into a secret world, which they kept secret even from each other. But while they dealt with the horror individually, when needed, they had one another to reach for in the darkness.

My older brother was married with a baby son. My nephew, whose first birthday was four days after Jed’s death, is the only person, aside from Jed’s girlfriend, who was mentioned in the suicide note. (“Tell Max I love him. And to all, a good night!”) My surviving brother barely had time to sleep, let alone grieve. But while I can only fathom how he balanced the enormity of new fatherhood with his despair over the tragedy, he too had a partner to help him see it through.

I, on the other hand, was a month shy of my 25th birthday — wedged between childhood and adulthood. I was consumed with figuring myself out: what kind of person I wanted to be, who I would fall in love with, what I would do professionally.

At the time, I was living with a boyfriend, but the relationship wasn’t built to navigate this kind of storm. We soon disintegrated, although I was too stunned and he felt too guilty to end it. I was, for all intents and purposes, alone. Jed had also been alone; it had been a bond between us. We were teammates in our shared youth and confusion. With Jed gone, I was the only loose end left.

To survive the loss, my parents were propelled to do something. They threw themselves headlong into trying to fix a problem, as they saw it, on college campuses. Why hadn’t the school understood Jed’s state of mind better? Should they have? Why did nobody know that Jed had kept a gun in his dorm room?

It became my parents’ mission to identify, and if they could, fix, these problems. I have no doubt that the creation of the Jed Foundation, which they founded in 2000 to promote the emotional health and prevent the suicides of college students, made it possible for them to brave the loss. For my surviving brother, he couldn’t allow my parents to embark on that journey without having some control and involvement in what became of their efforts.

But for me, the Jed Foundation seemed like an attempt to intellectualize something that was fundamentally emotional. It was too adult an exercise, too complicated to boil Jed — the breathing, living person I knew — into a cause. It was exhausting just to contemplate. And it was simply too intense. The Jed Foundation was the burden of my parent’s grief, made real — a fine laser point for what was otherwise an amorphous, unnameable dread. I bristled against the rest of my family’s efforts to create the foundation and at the first opportunity I asked to be freed from any involvement.

I needed to live my life, as best I could, clear and free of his death. And I did. For years. Until now.

Last year, I began to campaign to re-join the board. For more than a dozen years, the Jed Foundation has been working to create better mental health care for young adults, with partners like the Clinton Foundation and Facebook. It is no longer just my family’s mission; it has taken on a life of its own, with many people working tirelessly to achieve its success.

Asking to once again be a part of an organization that I left years ago is a tall order. And maybe some would say it isn’t right that I glom onto the success of others who have made it what it is. But I’m no longer alone, I am blessed with two small children and a supportive husband, and I finally feel mature enough to handle what the rest of my family instinctually understood. That doing something is healing.

Earlier this month was the Jed Foundation’s first gala fundraiser since I joined the board. And it was a wonder. With speeches from the likes of writers Andrew Solomon and Scott Stossel, and unbelievably, the pop star Demi Lovato, I did not have as terrible a time as I typically do.

Rather than feel alternatively guilty at not having helped create this legacy for Jed, or angry at having to be an unwilling part of it, I felt grateful. Grateful that really, maybe, it is making just the smallest difference to some kid. That some other Jed out there won’t go to the hardware store and buy rope and manage to tie a noose. That instead, that kid will find someone online, or a friend, or a professional, who is equipped to help.

Just like we change as we age, so too does our grief change with us. And because I’ve somehow, miraculously, made it out of the shadowy woods that is post-college anomie and into the comparatively sunny meadow of adulthood, I can finally give something to my brother who wasn’t lucky enough to see his way through.

Julie Satow is a freelance journalist who writes primarily for the Real Estate, Business and Metropolitan sections of The New York Times. Her work can be seen at juliesatow.com and on Twitter @juliesatow.