About a year and a half ago, my friend Ned left me. It was for the best, a sensible decision based on needs more than wants, safety rather than preference.

Ned’s health was declining; he was 87, living alone in a cottage on a small island Maine that, during cold months, and among other things, required him to stack firewood and haul it up a great flight of steps to feed the stove to heat his house. When it snowed, he shoveled his own driveway. And when he got sick that one week last summer, Ned’s only daughter Amie was in Arizona, caring for an injured husband, so I jumped in as much as I could. And when he recovered, she couldn’t possibly come as often as to Maine as she’d like and as often as Ned needed her, and he needed someone. I’m a working mother with two kids of my own. Neither Amie nor I could find a reliable or affordable caregiver. So the decision was made: Ned would go to an assisted living community. And so, just like that, after nearly thirty years of living on Peaks Island, Ned was gone.

When he moved away, I cried like crazy. Not just because my friend was moving away, and not just because, while standing on my front porch that August afternoon, I watched an ambulance zoom by to take him to the ferry dock to the fire boat to the mainland to the hospital after he’d fallen for the first time that week. No. I cried because I thought that big lurking moment of which I’d feared and anticipated had finally arrived. That his fall was the first tremor of that big and final earthquake, which, in the years since we’d first met, I’d done a pretty good job theoretically confronting and accepting the inevitability of. That moment in which my best bud, a person more than twice my age, would die.

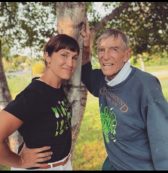

Mira and Ned

But Ned didn’t die. In fact, his hospital stay was quite brief and Ned sprung back into health. But instead of coming back home, he moved about across the bay and about forty minutes away to an apartment in a senior living facility called River’s Edge. It took some adjustments, but things between Ned and me also reverted back to something of a regular pulse, too. Rather than meeting spontaneously at at Peak’s Cafe on the island, we instead established weekly “Chowder Mondays” at a local fisherman’s joint in the old port on the mainland every Friday, right after I finished teaching at a women’s prison and just before I boarded a boat to go home to pick up my kids from school.

When I visited Ned at River’s Edge for the first time, Ned was a bit gruff and grumpy in showing me around his new environment. He seemed to drag his feet a bit down the beige carpeted corridor during my tour, and I heard him muttering Goddamnit while we waited for the elevator. In the dining room, we squirted coffee out from the sterling carafes then sat down at his regular table. In between sips and looking down, Ned skipped the small talk and instead questioned his most recent and big decision aloud. “I’m just not sure I did the right thing,” he kept saying, over and over. Then he said that it was difficult to make friends, and the coffee wasn’t strong enough. That everyone was too Republican. Too old.

Here’s what I find fascinating about Ned: He worked side-by-side with Jaques Cousteau in an underwater submersible. He lived in Greenland, studied climate change and slept on polar ice sheets. He sat in the bombardier seat of a WWII B17 Flying Fortress Bomber completely surrounded by a see-thru plastic nose piece, just to see what it felt like to fly. Ned has traveled around the world plenty of times, married thrice, is a Christian Scientist, never takes drugs or medicine, and still sleeps in the back of his Subaru when he goes on road trips. He worked at a newspaper back when he was 15 years old, back when they still used hand set type, and had to read their compositions backwards. Ned knows Ernest Hemingway’s son, and is a current member of the Explorer’s Club, is an avid sailor, and has a cat named Gilbert, whom he regularly walks on a leash.

I have done none of these things. I do other things, but here is one big difference between me and Ned: I’m forty-one and he’s more than twice my age. Here are a few things that we do have in common: Ned and I love reading old books. We love discussing all things Maine. We love the topic of doomsday prepping, survival-at-sea stories. We’ve had lengthy discussions on the subject of cannibalism. We have attended countless rallies, book launches, country fairs, and climate change discussions together, all this and more because of our fateful happenstance meeting at the cafe on Peaks Island, which sparked our friendship (I saw him reading a book and asked which one it was.) As with warriors in a brigade or kindergarten classmates, our bond was born through our shared circumstance, ours being simply of living on a small, isolated location: a small rock in the Atlantic Ocean.

“Do you think we would have met had it not been for Peaks Island?” I asked him not long before I began writing this essay.

“Probably not,” said Ned. “But I’m glad we did.”

And then coronavirus hit, and everything changed. First, as a trickle: a couple of cases popping up around Maine. Then a direct hit: an outbreak just outside of Portland, in a senior living facility. River’s Edge. Ned’s building took a big blow. Ned was quarantined, called me from his room, and told me the news. If everyone at his dining table got the virus, it was only a matter of days before Ned got sick, too. What if he dies? I worried. And what if he dies all alone?

Ned was quarantined, called me from his room, and told me the news. If everyone at his dining table got the virus, it was only a matter of days before Ned got sick, too. What if he dies? I worried. And what if he dies all alone?

I panicked and began calling him multiple times a day. Not long after River’s Edge’s quarantine, the entire state of Maine was put on lockdown as well. My son’s school was canceled for the rest of the year, as was my daughter’s daycare. Like the rest of the country, we were told to stay put, not leave our homes. Work from home. Overnight, I became a full time homeschooler with a simultaneous career. My kid’s school assignments kept coming, as did my work assignments. As the laundry piled up, my house turned into a kindergarten classroom/garage/muddy doormat.

I began burning out fast, and for the most part, the only time I had to myself was when I was sleeping (if that). Each day, the entire day, closely resembled the first five minutes of Saving Private Ryan. And then I’d get a text from Ned, wondering if I could chat. I wanted to respond by telling him that I couldn’t steal time to take a shower, let alone arrange a quiet space of peace and quiet to FaceTime with him (or really, a close up of his eyebrows), but instead I said, “maybe this evening” and then didn’t get around to it. As my husband, two kids, two dogs and I were all bungling around in our small home in those first few weeks of the pandemic, I didn’t even have a moment to go to the bathroom by myself, let alone maintain a friendship. Could it be that the distance in miles, rather than the distance in years, was going to put an end to my friendship with Ned?

This last year have caused the lines within life to blur together. We wear pajamas during work calls, our kids burst in during Zoom calls, wailing, and want to sit on our lap. We’ve been forced to adapt, and in turn, to reexamine our principals. What do we hold onto and what do well drop off? And just like with my need for time to write, I want my children to respectfully observe, not bogart, the time I reserve for Ned. If I can’t have a quiet conversation on the phone with Ned, then I’m going to have a loud, uproarious, chaotic chat with my kids clawing at me. Because this is not a part of my life I’m going to let drop off. I was raised in a home—and am raising my children in a home—where respect is aimed upward. Where the younger generation had a reverent respect of its elders, learned from them, spent time with them. I’ve learned that from these kinds of relationships, I’m handed one end of a golden thread. A thread that passes down wisdom, lessons learned from mistakes, secret stories and oral histories that, unless they’re passed on, and retold, will be lost. This is held sacred.

I recently saw Ned in person for the first time in months. He drove down from River’s Edge to the ferry landing in Portland, where I met him, both of us masked and both of us on opposite ends of a bench, our bodies one horse length apart. From behind his face mask, I could see his eyes swell with tears. “You have no idea how important you are in my life,” he told me. “You have no idea how much I depend on you.”

One thing about Ned is that he is one tough son of a bitch. During that meeting, he told me that not only had the virus gotten into his facility, but it infected everyone at the table he sat at, and killed at least one person. And yet, after 20 days alone (with Gilbert) in his room in quarantine, Ned never got sick. But when it comes to the impact of long periods of solitude, just like every person on earth, Ned is fragile. Sensitive. How important you are in my life. No one ever really wants to be alone.

From the bench, I slid I tossed a bag of homemade biscuits towards Ned, we walked towards his car, he got in. He turned on the engine to his car and, just before pulling away, called my name. “Hey Mira,” said Ned. “Have you ever heard this phrase, What’s worse than solitude is returning to solitude.’?” Then he drove away.

Often, I think about this: If I were Ned, or when I am Ned. Who will care for me when I am 90? Will I be alone? Am I prepared to be alone? Also, I think about my place in the universe. What is my role here? But I know the answer to this one completely: To give love and receive it. Ned is not an obligation. He is my kin. It’s a win-win. I keep him alive, and he reminds me of death, which really means, he shows me the beauty we have in this gift called life. Yes, there is isolation but there doesn’t have to be loneliness. Yes, there is death but there doesn’t have to be fear or sorrow. Outside, there birds are singing and have always been. The skies are clearing. Soon, there will be so many little green buds on the trees. Life is always here.

What is death but the soul leaving the body? And what is love? As the great poet Rilke puts it, love consists in this: that two solitudes protect and border and greet each other. Yes, Ned and I may be staring at each other through a computer screen, me mostly seeing a close-up view of his nose hairs, but in our connection, we are creating a sacred space. A space of “no matter where we are, we are in this together.” A space of understanding, of “you are me and I am you.”

Mira Ptacin is the author of the memoir Poor Your Soul as well as The In-Betweens: The Spiritualists, Mediums, and Legends of Camp Etna. She lives in Maine.