Lauren and Sydney (Courtesy of Lauren DePino)

By the orange gleam of the basketball-shaped nightlight, my ex-boyfriend’s 4-year-old son, Kellan, and I watched my iPhone timer count down. “Free maw minutes until bed,” he said. Earlier that afternoon, I heard him trail his father in the kitchen, coaxing him to count up. “Five-hundred-and-firty-faw,” he chanted.

“Five-hundred-and thirty-five,” his dad answered.

They kept going. But on the last night of my most recent trip to Philadelphia to say goodbye to the old, infirm dog I share with my ex, Kellan forsook his fascination with numbers for a question.

“Why do you love Sydney so much? Is it because she’s dying soon?”

Dying soon. I had tried to let it in, to breathe it in. But I couldn’t. Downstairs, I heard Kellan’s mother talking softly on a work call and the cling-clang of his father washing pots from dinner. On the living room coffee table was a copy of “When a Pet Dies” by Fred Rogers. I had spotted it earlier that week. When no one was home, except for the dog and me, I read it silently and cried.

Lauren and Sydney (Courtesy of Lauren DePino)

Now, here, on Kellan’s bed, Sydney, the nearly 15-year-old Australian shepherd my ex had brought me for my 24th birthday — the year we’d later break up — lay at my feet, breathing heavily. She was in renal failure, but that did not deter her from observing her evening routine: migrating from bedroom to bedroom, staying put until each pack member settled into rest.

I considered Kellan’s query. Do we love our loved ones more when they’re leaving us? When our shared hours become countdownable? Or does all the love we’ve felt over the course of someone’s life rise to the surface when we sense the end is near?

“I’ve loved Sydney all along, since she was a puppy,” I said.

“How did you know her?”

Kellan’s 7-year-old sister, Clara, was waiting for me in the next room to tuck her in. I knew she understood. Ross and I had dated for five years but had clashed as a couple. And though we’d gone on to meet other spouses, our friendship, like a sibling bond, endured. I told Kellan his father and I cared about each other long enough for me to love baby Sydney. And that every time Sydney and I parted over the years had been hard — when I dropped her off after her visits, when his family traded their rowhouse in walking distance for a house with a yard, when I moved from Philadelphia to Los Angeles to be with my fiancé.

I considered Kellan’s query. Do we love our loved ones more when they’re leaving us?

I did not tell Kellan I wished I could think of my time with Sydney without counting down. Chronic kidney disease had taken that luxury away.

“Is this your last goodbye?” Kellan asked. I didn’t know. Four weeks earlier, I’d gotten a text from Ross telling me Sydney’s numbers had gotten worse. That she wasn’t eating and other “not good signs.” I had packed my computer and booked a flight for what I thought would be my last visit with Sydney. Ross, his wife, and I had decided we’d do the unthinkable, though none of us could utter the words.

When my red-eye flight reached 35,000 feet and the cabin lights dimmed, I turned down the brightness on my phone and watched younger, spunkier versions of Sydney smile at me through the screen, her eyes large and brown like mine. I heard her howls, her playful growls, her paws clicking on the hardwood floor. Through my tears, I saw her black fur pounce toward me in a blur. I heard myself conversing with her in tones only she could construe. Our life together had been long, but it was still too short.

“Never, with dogs on guard, need you fear for your stalls a midnight thief,” reads an English translation of the Latin poem “Georgics” by Virgil. Five years after Ross and I broke up, I encountered a midnight thief of the most menacing kind — grief-begotten anxiety. My beloved grandmother had died suddenly and the day after her funeral, the partner I thought I would marry abruptly left. Sydney comforted me in the grim, sleepless hours of the night in a way no one else could. She loved me as she always had, perhaps more. I was enough to her even when I was broken.

When the vet arrived on the day we had decided to let Sydney go, Ross and I told her we couldn’t go through with it. Sydney still showed signs of joy. The vet agreed that Sydney did not display the gravity of her diagnosis, because we’d been taking good care of her — administering subcutaneous fluids, giving her an appetite stimulant and other medications, and feeding her foods she loved like homemade steak and trout. We would know when it was time.

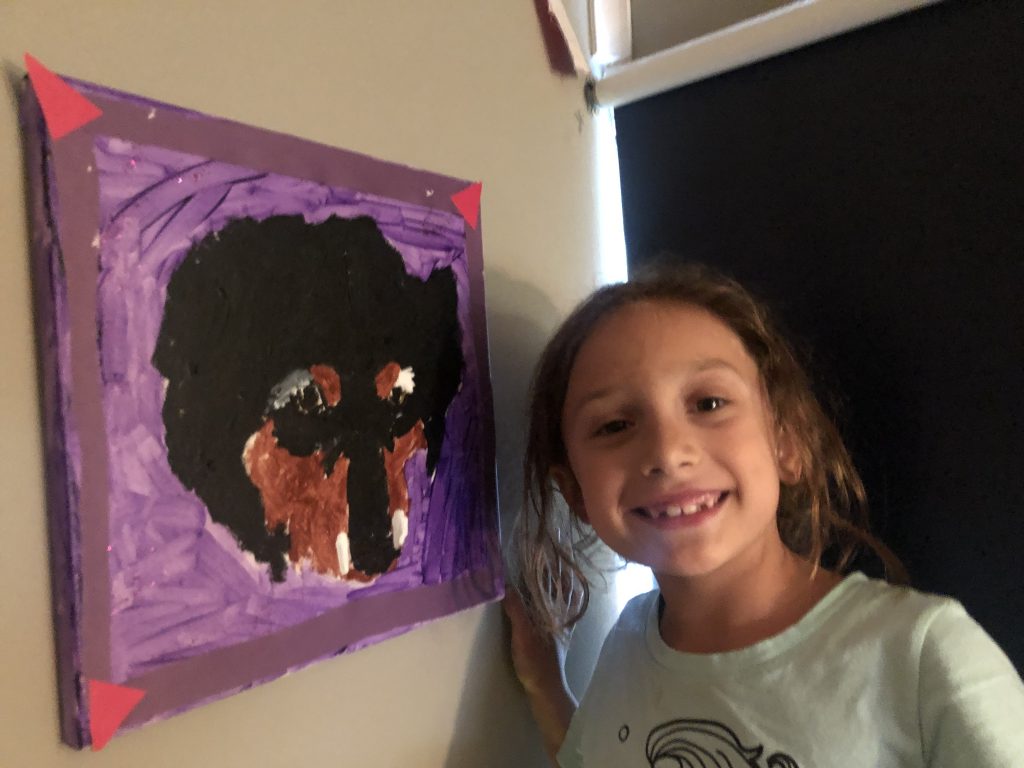

Clara with her painting of Sydney (Courtesy of Lauren DePino)

In the interim, in the liminal space between parting and not parting, between goodbye and not goodbye, I set myself up with my computer wherever Sydney lay, regardless of my own comfort. She slept much of the day. Sometimes, mid-snore, she’d lean her body on mine. It was heartbreaking to go on walks without her, past the familiar tall trees, the creek, and the peeping deer.

When I saw the vet again on my latest visit — a visit I didn’t think I’d have — I asked her how long Sydney had left. She said maybe weeks or months. Definitely not a year. Would I see her again? Probably not. I should say goodbye now.

But how? I asked other people for advice.

“Just love her,” my fiancé texted. When I posted my question on social media, many said there are no words; there aren’t supposed to be. My favorite comment was: “Whisper, ‘come back to me.’ You never know.”

In “When a Pet Dies,” Mister Rogers doesn’t use the word goodbye, not once.

Instead he says, “We can grow to know that the love we shared is still alive in us and always will be.” On that last page, there are two sets of families, one flying a kite and another riding bikes. All of them are smiling without their pets, which aches my heart.

By the time I boarded my flight home, I had a new video of my dog to watch on the plane. In it, I talk to her, but this time she’s supine and tired. “You’ve made my life infinitely better,” I say. She opens her eyes, and she sees me.

It’s been five months since I last saw Sydney in person and, miraculously, both her energy and her appetite have returned. She’s not better; she never will be. But she’s made it clear she’s not yet ready to go.

For now, what gives me the greatest peace, what brings me nearest to solving this problem of goodbye, is observing the way Sydney’s human siblings do it.

“I googolplex love you.” Kellan said to her on my last visit. “No, infinity!”

“I love her infinity times infinity,” Clara joined in.The wisdom in their words calms me, sends me into a state of mind where I can love Sydney without obsessing over how much time we have left, over how many bonus goodbyes I might get. There is still a threat of her imminent departure, and I’m still afraid of losing her.

But now I know what the children know — that infinity holds within it the boundlessness of our love.

Lauren DePino writes about mortality, hope, and the art of noticing. She’s on Twitter @YourItalianHope, Face