Dear Noah Kahan,

On April 13, 2024, I watched you perform at the Bell Center in Montreal at the end of a hellish week while 21.5 weeks pregnant with identical twins.

After an uneventful first trimester, they were diagnosed with a condition characterized by unequal blood flow across the shared placenta, which is nearly always fatal to both babies if untreated.

In the wee hours of April 9, we drove down our normally quiet Vermont road, heading for emergency surgery at Yale in an attempt to sever the problematic vessel connections. Our departure was delayed by a string of taillights, as thousands of total eclipse chasers returned home.

I was filled with terror during the operation. But the doctors were cautiously optimistic post-op, and I was cleared to go to your concert a few days later. The next morning, we saw the babies’ heartbeats; then again, two days later, before I headed to Montreal.

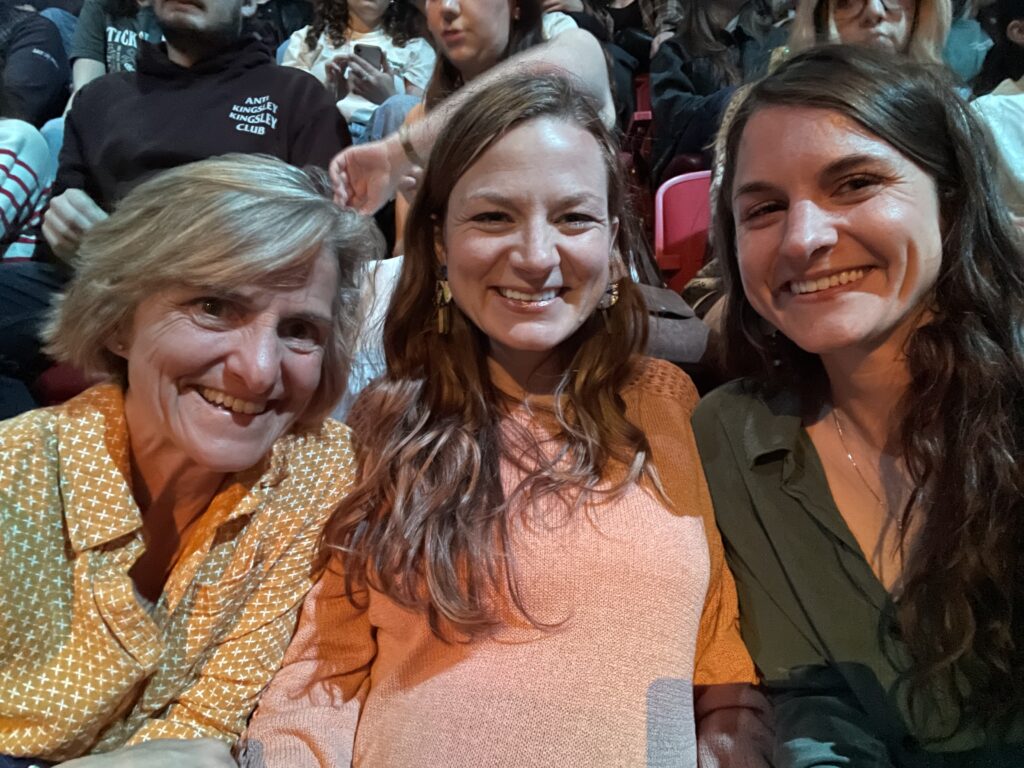

I arrived at your show with my mom and sister, my body still tired and sore from both the surgery and adapting to my growing abdomen. As your opener Jensen McRae played, everyone stayed seated and I was grateful, unsure whether I would have been able to stand. But when you ran on stage and began singing Dial Drunk, the entire stadium stood as one–except for seven of us in a center balcony section. By some miracle, another pregnant woman and her partner were seated directly in front of us, and in front of them an elderly couple, giving us an unobstructed view of the stage. A small nod from the universe.

The author’s mom, the author, and her sister at Kahan’s Montreal concert (April, 2024)

You played Godlight about halfway through the show. I’d never heard it before, but something about its bittersweetness and nostalgia spoke to my core. I felt myself, along with the rest of the crowd, lean forward to take in your words—your gratitude for where your career has taken you, and the wistful knowledge that some changes in life are permanent and beyond your control. We nearly made it through your entire performance before giving in to pregnancy fatigue and walking out into the night to the sounds of Stick Season.

Two days later, my husband and I learned we had lost one of the twins. We’d returned to the hospital for what had become multiple-times-a-week ultrasounds. The brusque ultrasound tech—the only male in the practice—delivered the news so casually and without any attempt to find a doctor, social worker, or support, that we thought for a moment it was some kind of sick joke: “I’m sorry to say that one of your babies didn’t make it and no longer has a heartbeat.”

I had to stay on the table for the rest of the exam, my husband squeezing my hand, tears rolling down our cheeks, in shock and disbelief. The only thing keeping us going was the thought of our other baby, who I could still potentially carry to term.

Two weeks later, my body went into extreme premature labor—a small risk from the surgery and the damage to the placenta. We spent a week in the hospital, trying to stave off delivery—an essentially impossible task. Ultimately, we couldn’t buy enough time to save our second baby, who I delivered alongside her sister at 24 weeks. Resuscitation was hopeless for her tiny body, which had already been through so much and was born four months too soon.

Time since has been a blur. The pain of losing our daughters has been unlike any I have ever known. I thought I knew a thing or two about grief and loss. It was not our family’s first rodeo learning the ropes of a hospital, or becoming overnight experts in an impossible diagnosis, including having lost my dad to a one in a million cancer before he turned 60 and before I turned 30. It was not the first time I had watched a family member die in front of me. But there is something unique to the pain of not being able to save your kids, to a loss coming out of order. I am left trying to understand how to grieve and honor my girls, when I never got to know them or who they would have become.

A few days after returning from the hospital, Godlight came up on my playlist. I’m sure the lyrics have nothing to do with losing a child, and yet…

To know me is to hate me

Is to hate what I’ve become

It’s to have it in your hands

The one thing you wanted all your life

It’s all mine

It’s a hole I can’t fill

It’s a curse I can’t break

And I gave my soul to it

And I cannot be reclaimed

I’m not the way I was

I’m not the way I was

I held our tiny babies in my hands after they were born. I marveled at how two beings could be so perfect, even as I was losing them. I thought of how part of me had always wanted three kids, having grown up in a large, dysfunctional, fun, chaotic family. How even though I know my son will grow up to be a raging feminist, I also wanted daughters to follow in my wake—badass skiers, boundary-breakers, sustainers of humanity. I realized there would be no way to fill the hole that should have been occupied by them. That I was coming home a “fucking alien,” having crossed a threshold few could follow or understand.

There was, and is, hate too. I hate freezing when someone asks how many kids we have. I hate how I bristle when someone calls it a “miscarriage,” because I didn’t have one. I hate that I’ll always resent those with uncomplicated pregnancies, untouched by this kind of loss. I hate that I couldn’t save our daughters. That this happened. That there will never be answers.

Even more, I hate that in another state, old white men with no idea what it feels like to live this nightmare in your own body could have forced more anguish on top of our agony. I hate that we live in a country that underfunds women’s health and chips away at our bodily autonomy. That we lack the language—and the will—to understand how pregnancy can go wrong: the babies and futures lost, the heartbreak of being told a pregnancy isn’t viable, the D&Cs, the IVF mazes, the aftermath. That so many of these realities remain unspeakable—especially to the very people in power to change them.

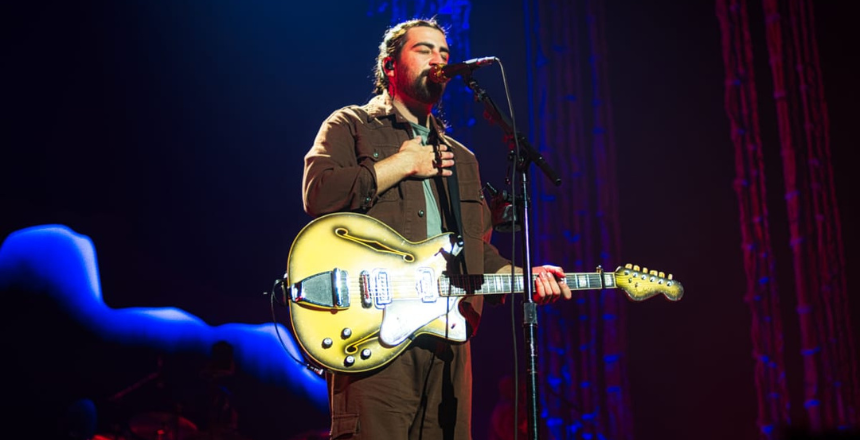

The author’s view of Noah Kahan’s Montreal concert, 2024

I cry when I hear Godlight now. But it brings me closer to my girls. Thank you for lyrics that somehow see into my soul and into this impossible experience. I survived the seemingly unsurvivable. And yet, I’ve also witnessed a dimension of love and beauty I never knew existed. I didn’t know how deeply you could love someone you never met. My daughters have changed me in ways I cannot unsee or undo. They are literally a part of me—their cells still in my body through fetal microchimerism. I’ve given myself permission to seek what makes me truly happy. I quit being a lawyer. I’m open to an unconventional path. I’m taking more vacations, spending summers off-grid at our family cabin in Ontario with my son. I’m healing and grieving without worrying about resume gaps. I’m writing. I’m a firstborn daughter learning that I can have needs. I’ve seen a beautiful side of humanity—nurses who hung fairy lights and took handprints, family who crossed countries to be with us, people who remember our daughters’ names, the trees and flowers planted in their honor, the donations to the wilderness girls’ camp we loved. I know now: life is too short. I’m not who I was—but somehow, that might be okay.

With love and gratitude,

Haley Peterson

Haley Peterson is a writer, recovering attorney, mom, and avid outdoorswoman living in the Green Mountains of Vermont.