“Statistically my time was up at least a year ago. But I’m still here,” wrote my childhood friend Marisa at the top of her Facebook note “25 Random Things About Me.” I had read and re-read her list so many times I’d nearly committed it to memory.

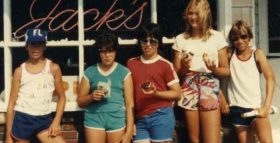

Marisa and I met the day her family moved onto our street in suburban New Jersey. She was the curly-haired impish little sister in a gregarious Italian Catholic family. I was a stringy-haired bookworm — the oldest sibling in a family of reserved Protestants. Her brother was inseparable from my brothers, and our parents barbecued together while we played hide-and-seek in the woods on summer nights.

Marisa discovered the marble-sized mass in her left breast 10 months before her wedding to her college sweetheart, David. She was 30. After a lumpectomy, a dozen rounds of chemotherapy and 30 radiation sessions, Marisa and David said their vows while my mother passed a packet of tissues down the church pew. They donated a portion of their wedding gifts to cancer research and settled into a tidy brick home on Philadelphia’s Main Line.

Meanwhile I had married my own David. We had two sons and lived in a New York City apartment cluttered with books and toys. We were hectic but happy. I saw Marisa at our families’ annual Christmas dinners in New Jersey; mainly we kept in touch through Facebook.

By the time Marisa was 39, the cancer was in her liver, spine, skull, ribs, hip and lymph nodes. She responded by focusing on what made her happy. Small things, like her Facebook Random Thing #12 “I’m addicted to Us Weekly” and #15 “Raisinets.” David’s love warranted two entries: #6 “I think my husband is the funniest person I know. And the most loyal.” And # 25 “I believe my husband and I were truly meant for each other.”

Marisa’s struggle had made me profoundly unsettled. After reading her Facebook list, I began waking up at 3 a.m., trying to catch my breath. In our darkened bedroom, I’d sit against the headboard, knees pulled up to my chest, and think about mortality — Marisa’s and my own.

To ease the anxiety, I read. I devoured so many books about life’s purpose that my husband was left shaking his head every time the UPS man delivered a new one. I discovered that seekers and sages from Socrates to Thoreau, Rumi to the Dalai Lama have long implored us to live with the end ever-present in our minds. A psychological study claimed that thinking about death could actually be good for re-prioritizing goals and values. Even Apple’s Steve Jobs asserted, “Death is very likely the single best invention of Life. It is Life’s change agent.”

In a move I thought would make Marisa’s playful eyes roll — that is, if I had told her about it — I decided to test this wisdom by living a year of my life as if it were my last.

While I was not in the habit of praying, each morning I would close my eyes and dedicate my project to Marisa. Then I would fill in the blank, “I don’t want to die without…” After Marisa wrote to tell me how ecstatic she was about a vacation in Italy she had taken between chemo sessions, I booked a trip to Turkey, which I had been putting off until my kids got older. David, the boys and I drank fresh-squeezed pomegranate juice on cobblestone streets and watched the Whirling Dervishes spin into a trance — one outstretched arm pointed toward the heavens, the other toward earth.

Next I tackled work. I used my flexibility as a communications consultant to develop a pro-bono campaign for refugees in North Africa. My income shrunk, but my days felt purposeful. I went on a 10-day silent meditation retreat, planted tulip and daffodil bulbs in a sooty plot in the shade of the Williamsburg Bridge, and snapped at my kids less, imagining each interaction could be our last. David and I held hands watching “Saturday Night Live” re-runs.

Slowly I understood that my quest was an invitation to participate more fully in everyday matters. While I had been looking for meaning along the banks of the Bosporus, answers were just as easily found in my newly flowering garden where elevated trains rumbled on tracks overhead. Meditating at home on a floor strewn with LEGOs felt even more useful than sitting on a perfectly aligned cushion in a serene hall. I cried openly and often for Marisa and her family, and in gratitude for her unwitting gift to me.

Toward the end of my 365-day experiment, Marisa’s doctors told her there was nothing more they could do. I arranged a babysitter and drove to her parents’ house where she was staying. “You might think sitting with someone who is dying means you will be having big conversations about the meaning of life,” a Zen hospice chaplain had advised me. “Wrong! Sometimes, all that’s called for is to just show up and watch ‘Jeopardy’ together.”

I found Marisa lying on the couch, staring at the TV, which was off. She turned to greet me, her voice thin and ethereal, caused by tumors covering her larynx. We fell into an easy recitation of our childhood stories. How we had allowed our brothers to zoom bikes off a ramp and over us à la Evel Knievel as we lay on the asphalt holding our breath. The summer her family rented a Winnebago and, deciding that campsites weren’t for them, parked it in the driveway of our rental house at the beach.

“Every big childhood memory involves you,” she said, her eyelids heavy.

“I know you’ll get b…” I began to lie, but then closed my mouth.

I took a slight step back. She looked older than her 40 years. Her hair was now short and patchy, her skin ashen gray.

I desperately wanted something extraordinary to happen — a pearl of wisdom to be uttered, a deus ex machina to appear. But in that same sunlit room where we had spent countless hours playing, everything felt still and ordinary.

In what was to be our last moment together, we leaned in to kiss each other on the cheek, as always.

Marisa died on November 22, 2010 — five days after my year-to-live experiment came to an end.