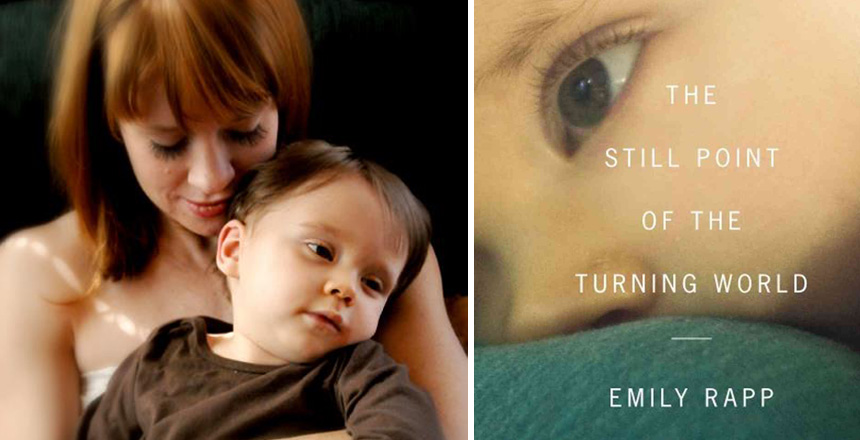

The author with her son, Ronan; the cover of her recent memoir about parenting a terminally ill child. (Portrait by Jennifer Esperanza)

My son, Ronan, died in February of Tay-Sachs disease. He was almost three years old — his expected lifespan after he was diagnosed with this terminal illness at nine months old. The first part of his life, before I knew he was sick and would die, was chaotic and full of joy. These last nine months since his death have been the same, only marked by his loss, which both complicates and amplifies the chaos and the joy.

Just after Ronan was diagnosed, when he still looked like a “normal” child but his sickness was known, people often said to me, “I cannot imagine,” and “I don’t know how you do it.” Some were taken in by the drama of a dying child. They wanted to watch what I would do, see me suffer, feel pity. As much as possible, I was careful not to grieve in public, because the reactions of others often felt voyeuristic. The grief was mine, and I tried to own it alone and in my work. I shared the full truth of it only with the people closest to me.

Watching a beloved child regress into a vegetative state and die is a living hell, no doubt, but so is living without that child. I no longer have Ronan’s sweet body to sniff and snuggle in the morning or at night. When he was alive and I was teaching a class or leading a workshop, I would imagine his body, his face, still in the world, and I would feel both comforted and heartbroken at the same time. I wanted his life to be over — for his suffering to end — and I also couldn’t bear the thought of him no longer in the world.

He’s been gone for nine months now. It could be three days, it could be three minutes or 300 years. People have moved on. There are other sick people to worry about, another crisis that must occupy attention. But for those of us who have lost children or anyone we love, time stops, morphs, stretches, shrinks, and confuses. Our missing one is both present and absent, and each of these states is acutely felt.

In our culture, we are expected to “get over” our losses quickly, and not talk about them anymore. Now is when I want to talk about Ronan the most, when I fear that his memory is leaving the world and that his life will get lost in a long string of lives that have ended. We all feel this way about the beloved; they are singular and only, and they are this way after their death, for many — and then months and years later, only for their primary mourners. This is as it should be, but it is also doubly alienating for the person who still feels the loss each day in a visceral way.

How does a griever make it through this period of after-death? I am still facing a lifetime of missing my child, but if someone were to ask me how this is done, I would make this list:

• Exercise

Grief rips away familiar ground. Part of this feeling is the sense of being disembodied or disconnected from your familiar self, from your body. Sweating, feeling the pumping heart, the moving limbs, helped me stay present, and it still helps me work out the anger and sadness I feel when I look at pictures of Ronan, or think about particular moments, either joyful or sad.

Related

• Falling in Love

This was a surprise to me, a great gift, but it has been crucial in my recovery process. Ronan’s father and I separated during his illness and divorced shortly after our child died. But when Ronan was approaching his last six months of life, I met a man with whom I fell in deep love. He was able to hold the experience I was having, and also hold me. I received a lot of advice (and some judgment) about waiting to start my life or to make any changes until Ronan had died, but having the support of my partner during those last six months felt essential to me. And it still is. My son’s life was ending. Mine was not. To want to live is not a failure of love, but a tribute to the person you’ve loved and lost. Grievers also need to open their lives to possibilities. Sometimes, at your most broken, you are able to make the strongest decisions. Your life is stripped down to the point where it is impossible not to know what you want in your life and what you do not.

• Working a Lot, and Then Working Less

I worked while Ronan was sick, at the two teaching jobs I’ve had for the past two years. I traveled for work. I wrote. Again, there was judgment, but not everybody grieves the same way, and just as a “regular” parent could not be with his or her child 24/7, I also could not be with Ronan all the time. I wanted to make my world big — for me this was a survival mechanism — but the caretaker of a dying person is somehow not expected, in some ways, to survive. How many times have you heard she was never the same after the death; it destroyed her. It often seems that people expect this, even (in the most sinister analysis) want this, as a way of completing the tragic story circle.

Against everyone’s well-meaning advice, I couldn’t rest while Ronan was sick. I would teach my classes with a smile on my face, a great circus act, and then sprint up to my office, rip off the mask and weep. In the months after Ronan’s death, after the panic of losing him and the initial stages of both relief and mind-numbing grief, I have found that I need to work less. I resigned from one of my teaching positions. I spend more time doing nothing. In work I felt relief; I could pretend nothing terrible was happening. But the terrible has happened, and I’m resting now.

Sharing photos of Ronan — from all stages of his life — makes me feel connected to those stages, and is also a way of saying, “He is not forgotten, he was special, and this is not over for me.”

• Friends and Family

So many people came to my house in Santa Fe and held Ronan. This surprised some, who expected me to hold him close, never let him go or allow him out of my sight. I’m so glad I allowed others to care for him, to fall in love with him, to remember him. I feel that his life — its beauty and singularity — reached many. This comforts me on the days when I think about his three short years on this earth. I recently had this exchange with my college roommate, who asked, “When do you miss Ronan the most?” I told her I missed him at the night and in the morning, but it was constant. I told her I missed the way he smelled, even when he woke up with a stinky diaper or a sleeper full of poop. “That was Rone,” she wrote. “Happy in every situation.” Someone else with a memory. Someone else carrying a torch. This matters to me.

There are no foolproof grief management tools, just effective grief management strategies. There’s a difference. To manage a feeling implies tying it down, forcing it to go silent, eliminating hurt or emotion. Grief will not be tamed in such a way. The above strategies worked for me because they felt generous and open. They were not prescriptive. They did not provide stages or levels of grief to work through, but allowed for flux and motion, for stepping back and then stepping forward. They gave me the ability to ask for what I needed, accept help and have faith that although Ronan’s life ended far too soon, mine didn’t have to. And although some people will not remember him, I always will.

Emily Rapp is the author of “Poster Child: A Memoir” (Bloomsbury USA, 2007) and “The Still Point of the Turning World” (Penguin Press, March 2013), which was a New York Times bestseller. She is a professor of creative writing and literature at the Santa Fe University of Art and Design in Santa Fe, N.M.