The grief experts advise the mourner not to make any drastic life changes within the first year. Because I am an idiot, I make all the life changes within the first six months.

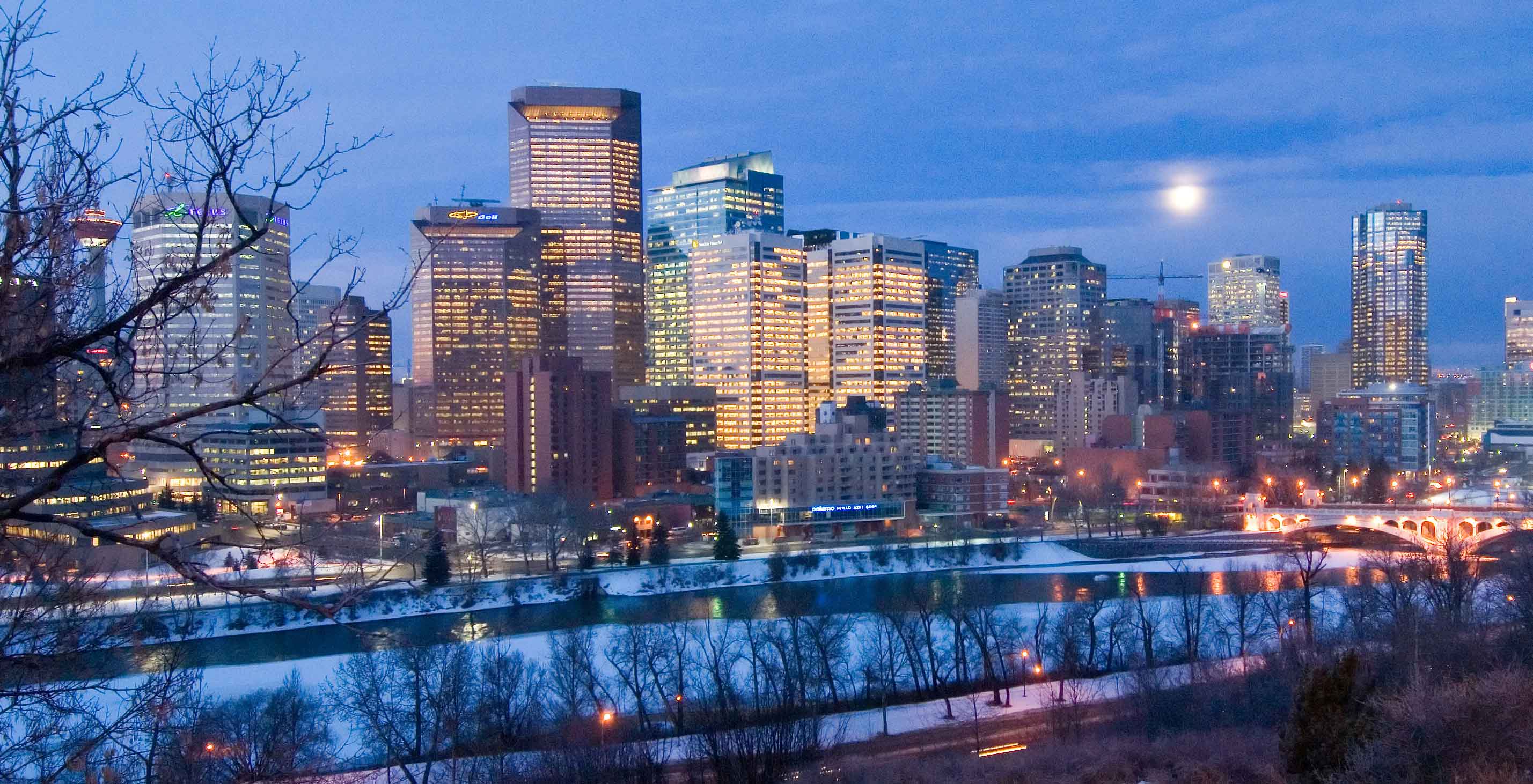

I’m still in shock at the post-service reception in the basement of Knox United Church in downtown Calgary. I keep drinking, but my mind is cotton. The room is packed with extended family, childhood friends, dance teachers, the local music community, a small handful of my brother’s ex-girlfriends. One his bandmates collapses, sobbing, in our dad’s arms.

I am in shock and my mind is cotton and I keep drinking, but I still feel. In fact, I feel everything heightened, in particular the outpouring of love and community that has swept over my family after Chris died unexpectedly in his sleep, at 26, on the day before my 32nd birthday.

Three months later, my husband and our cats, Amy and Bella, pack our things into a U-Haul and depart from the humid coastal lefty city where we’ve made our home for eight years. It’s an eleven-hour drive to the arid conservative oil-town of my birth. I’m a different person from when I left: I don’t eat meat anymore. I’m more mature, less erratic. My politics have shifted. To the shock of my brother’s death, I add cultural and geographical shock.

My husband and I move into my parents’ basement. We don’t have jobs lined up: he’d been unable to acquire any sessional teaching work for the summer in Vancouver, and my 12-month term as replacement for a managing editor on leave was coming to an end. Rather than try to stay and find work, we’d decided to book it out of town.

Immediately I realize we’ve made a mistake. Every iteration of Calgary Self from birth to age 24 springs up and slaps my face at every corner. We meet friends for drinks at bars where I used to pick up one-night stands. We find a new vet clinic down the road from my junior high school. My train station hangout from every day of eighth grade is now the departure point for job interviews. It still smells like hot concrete and loneliness. We cruise the strip mall where I failed my first driver’s test, looking for a coffee shop. This city is a cesspool of regression.

Worse: the absence of my baby brother and best friend. He was always peacemaker, resident clown. We fight with my mom about kitchen cleanliness and in the absence of my brother’s calming presence the fights turn to screaming and hysteria. Sometimes I visit my best friend of 20 years to escape the stress of home-not-home. Her house is around the corner from the crematorium where we sent Chris off in a wooden box. I grow accustomed to driving through tears.

The cohesive community of deathweek has mostly vanished, and I’m lonely and bereft. At night while I wait for medicated sleep my feet walk their usual routes in Vancouver. Now I’m on Victoria Street. Now Adanac.

My heartbreak is the size of the city that is no longer my home. I miss the warm humid air and the ease with which I could move through the city on foot, bike and transit. Calgary is a confusing loop of urban sprawl and cul-de-sacs. I miss my friends, the artist-run centers and literary reading series, the monthly dinner gathering of women writers. I miss the fruit stands in front of Donald’s Market. Here the closest grocery store is more than half an hour away on foot. I thought I would find my brother in Calgary, but he is not here, though we sleep 12 feet from where he died. We’re rent-free lodgers in my parents’ home in the suburbs, and although we recognize our privilege in this, we feel trapped and insane.

I gain 15 pounds. My husband gains 20.

Acclimatization happens so imperceptibly that I don’t notice it. Two winters pass, and I get used to the dryness of the air. I take a semester of skills upgrading and find a good job. Bella cat dies of old age. We move, and move again when the first house turns out to have slummy landlords. The second house is at first too big, but we settle in. We get another cat. We keep living. We reconnect with old friends and make new ones. I join a support group and make friends with other siblings of lost sibling.

Eventually it becomes clear that the community I saw at Chris’ funeral was always there —I just had to stitch it together for myself. Now I have many homes —Vancouver and Calgary. Before Chris died and after. It’s okay. I don’t mind the commute.

Nikki Reimer’s writing has appeared in Lemon Hound, The Rumpus, Poetry is Dead, Joyland, SubTerrain and The Capilano Review. She is the author of “[sic]” (Frontenac House, 2010) and “DOWNVERSE” (Talonbooks, 2014).