On a hot August day in Colorado, I put on a silk shirtdress and sandals, tied my hair into a ponytail, and headed to my brother’s funeral. In Colorado, the altitude makes the sun feel more intense. My skin prickled and my cheeks turned red. The thin air made my chest feel tighter than it already was. I kept stopping to catch my breath. Was this really happening?

Alan had died suddenly a week before. He was 43. His death was unexpected and unexplainable. What started as an asthma attack ended when his heart stopped beating in the ER. No one, not even the doctors, could explain exactly what went wrong. His death, it turns out, wouldn’t be the only surprise that week.

Pulling open the heavy carved wooden doors of the church, I was hit with a flood of air conditioning and the tin sound of “Hark the Herald Angels Sing.” Recorded trumpets blared from surround-sound speakers, as festive voices declared, “glory to the newborn king!” Christmas carols played on a loop as people gathered and took their seats among festive greenery and red flowers. A wall of photos showed Alan at various stages of his life wearing Christmas sweaters, standing in front of a twinkling tree, sitting on Santa’s lap. All the while, in the background, was “Joy To The World,” “Oh Holy Night” and “God Rest Ye Merry Gentleman.”

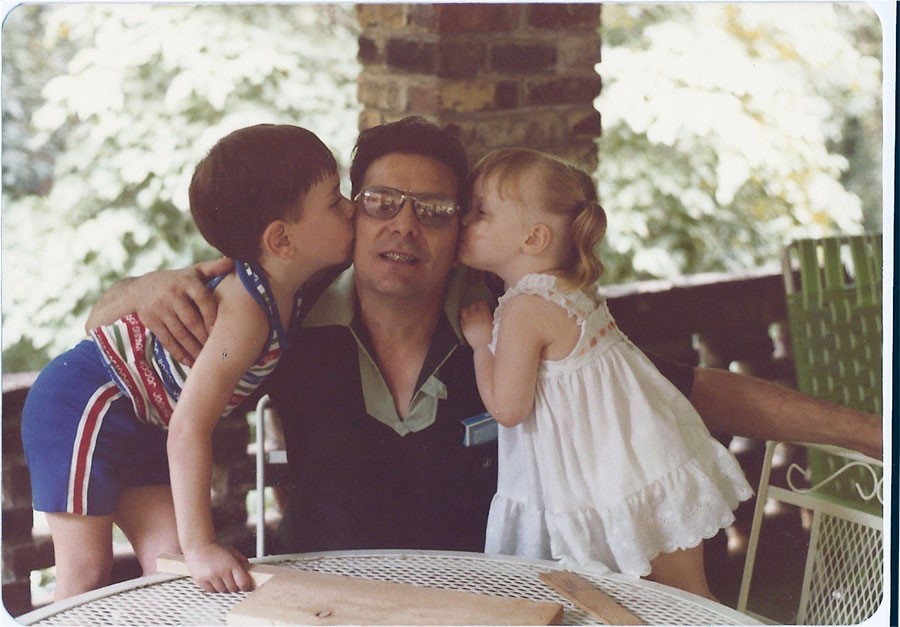

Alan and Gina with their grandfather (Courtesy of Gina DeMillo Wagner)

The juxtaposition of holiday music in August was disorienting. Hearing it at a funeral was even more confusing. Some of the mourners filing into the church looked at me quizzically, as if expecting an explanation. I didn’t have one. My parents had done most of the funeral planning. I wasn’t sure how we would be honoring Alan that day. A few people smiled, because they knew that this was exactly the kind of funeral Alan would have wanted.

Alan wasn’t typical, so why should his funeral be? My brother lived (and died) with a genetic abnormality called Prader-Willi syndrome. This led to cognitive delays. It was as if he was a 5-year-old in a grown man’s body. It also caused severe mood swings, obsessive-compulsive tendencies, and hyperphagia (insatiable hunger). Alan was obsessed with food, with music and with Christmas.

Growing up, it wasn’t unusual to find Alan wearing his footed Christmas pajamas well into summer, playing Bing Crosby’s holiday cassette on his Walkman and singing along at the top of his lungs. From the time he was able to hold a pencil and write, Alan scratched out letters to Santa. He made lists of the toys he wanted and the holiday food he wanted to eat. He was always disappointed Santa wasn’t at the mall year-round.

At darker times, Alan’s condition caused him to be violent. He’d break windows, overturn furniture, and punch anyone within his reach — often me. The hyperphagia led him to eat everything in the pantry, to forage for food from the trash, to consume toothpaste. As much as I loved Alan, growing up with his behavior was extraordinarily difficult. Over time, my family and I came to embrace his Christmas obsession, because it represented his happiest, most peaceful moments. It’s only fitting that his funeral reflected those moments, too.

Some people say that funerals are for the living and not the dead, that you should do your best to make the mourners feel comfortable, to give them “closure.” I say that how you choose to honor someone who died is a personal decision. Ideally, your loved one will have communicated their wishes to you. But when your loved one is disabled, unable to communicate, or dies suddenly and without warning, you’re left to wonder what they might want, how they might best want to be remembered. You honor the person you lost the best way you can and help yourself move through the loss the best you can. Death has no rules or etiquette, so why should funerals? In the end, Alan’s service was as unique as he was. It honored his passions, his character, his gifts for capturing joy and magic year-round.

I spent much of my life trying to untangle my mixed feelings toward my big brother, to make sense of his disability and our tumultuous childhood. It wasn’t until he died — until his Christmas-themed funeral in the August heat — that I realized it didn’t have to make sense. I didn’t have to choose between the often-ambivalent feelings I had toward him.

And so, at some point during the chorus of “Silent Night,” I gave into it and let my tears fall. I gazed at my brother’s casket and wept for the loss of him and the loss of hope for a different life for him, a different relationship for us. I let go of the idea that his death, his life, this funeral would make sense. In doing so I began to come to terms with the reality that when I stepped out of Christmas and back into the summer heat, I would be doing so without Alan.

Gina DeMillo Wagner is an award-winning writer based in Boulder, Colorado. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Washington Post, Shape, Self, Men’s Journal, Experience Life, and more. She’s at work on a memoir about growing up with a disabled sibling.