When the first World AIDS Day was held on December 1, 1988, I was 10. My parents had just gotten divorced. My law professor father had moved out, to a tiny apartment on the campus of Eastern Kentucky University where he taught. My mother, a middle school teacher, moved my brother and me to a rental house across our small Kentucky town. Suddenly everything in my life divided and contracted: our physical space, the time we spent with each parent. We ran into my father at a discount box store in one of the home aisles, shopping for his new cement-walled two-bedroom.

I can’t remember how they explained the divorce to us. Maybe it was the classic “We just don’t love each other anymore.” Before they split, they spent hours talking in their bedroom, while my brother and I read or watched TV or did homework or played kickball with the neighborhood kids. “Why does it always look like you’ve been crying after you’ve talked to Dad?” I asked Mom once during that time. I knew it was a naïve and childish question even as I asked it; I remember thinking that perhaps the simplicity, the naivety itself, would draw out some answers. “Because I’m sad,” she said. No dice. I think by that point, I’d lived with the subtle currents coursing underneath our home long enough to know not to ask further.

By World AIDS Day four years later, in 1992, my father had died. Histoplasmosis, known as “caver’s disease,” found in parts of Africa and the Ohio River Valley, an hour or so north of where he lived, had hit his lungs and moved on to his brain, where it created lesions. It’s a common infection among AIDS patients. My father had started acting bizarre, then had brain surgery, then gone down, fast. He told my younger brother and me in the spring of my eighth grade year that he was HIV positive, and died five months later.

I did nothing to commemorate him that first World AIDS Day. I was a freshman at a high school where people drove to school with Confederate Flag bumper stickers on their pickup trucks. The movie “Malcolm X” had just been released, and beefy football players wore T-shirts with the flag that read “You wear your X, I’ll wear mine.” In class we held a furious and formal debate about whether gays should be allowed in the military; I passionately argued against my boyfriend’s close-knit group of friends, ROTC guys who’d go on to join the Air Force. (I lost.) There was no way I was telling anyone except my boyfriend and closest friends that my father had died of AIDS, or that he had been in the closet his whole life. Which was worse? At the time, they were both seen as equally shameful.

Related

For the next 21 years, I tiptoed around World AIDS Day. Sidled up next to it, felt it out, ran away. I couldn’t win. We had barely visited my father’s grave, and the guilt I felt over being a bad daughter — what kind of a daughter doesn’t try to keep her father’s memory alive, doesn’t keep photos of him around, doesn’t leave flowers at his grave? — tore me apart, leading me down several self-destructive paths in my 20s. I wanted to connect with his memory, but every time I got close, I drew back, stymied by my own guilt, the shame I still carried, the fear that I was betraying my mother. Would I be a bad daughter to her, my remaining parent, who had loved and supported me through every crazy-seeming decision I’d made, who had her own heartbreaking story to tell? And World AIDS Day was larger than my father, too — it wasn’t just him; it wasn’t just that it had impacted my family so greatly, but that it had impacted our world so greatly, and is still out there. I wanted to be some kind of an activist, on some small level. Instead, I did nothing.

The feelings layered on top of me like multiple blankets, ultimately immobilizing me. And then it was December 2, and December 3, and December 4. Next year, I thought. I’ll do something next year. I didn’t even know what that “something” might be. Go to a World AIDS Day event? Write about my father? Light a candle? When you are asked to forget, even something that simple seems melodramatic, overdone.

In my early 20s, I met someone else who had lost a parent to AIDS: Alysia Abbott, a writer and memoirist. Alysia’s story is vastly different from mine — her father, an out poet in San Francisco, had raised Alysia on his own; he also died in 1992, and Alysia had left college early to care for him — but I felt both jolted out of my isolating cocoon and immediately drawn to Alysia. Here, finally, was someone else who could understand.

Last year, after Alysia wrote an acclaimed memoir about her father, we decided to try to find others like us. We wanted to hear their stories. We wanted the world to hear their stories. We knew we were not the only ones — we couldn’t be. Outside of today, World AIDS Day, we don’t focus much on the disease anymore in this country, in our haste to declare it no longer a death sentence, but in the American South, it’s not over. Among young gay men, it’s not over. There are many populations for whom it’s not over. And for people like us, families like ours, who grew up in the shadow of AIDS, even if we did try to forget, it was never really over.

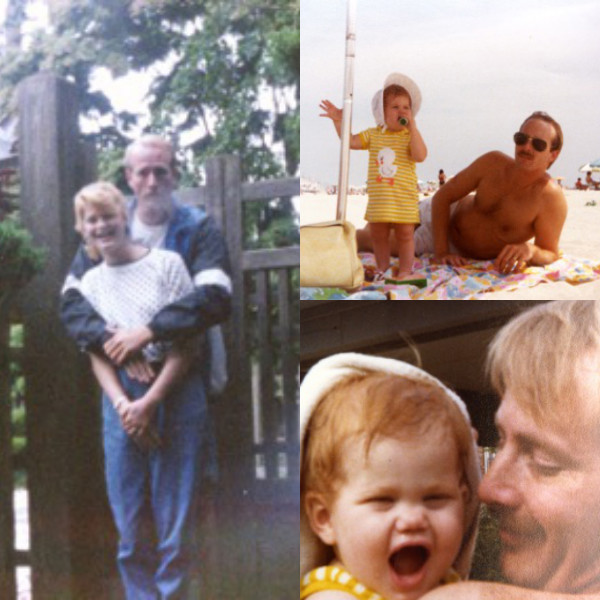

So Alysia and I launched The Recollectors, a website to re-collect the stories of the parents lost to history, with oral histories, original essays, book excerpts, interviews and photos with other “Recollectors”; we’re also posting #ThrowbackThursday photos from Recollectors on Facebook and working with partners to share stories in other ways. When our culture has swept AIDS under the rug, even the simple act of posting a photo of a parent who died is a powerful piece of activism.

I cried the first time we received an email saying “I’m one of you.” And then they kept coming. Mothers lost, fathers, stepparents. Dads in the closet, proudly out dads, half-closeted dads, addict dads. Addict moms. Parents who were hemophiliacs or had undergone blood transfusions. Children who still tell people their parent died of cancer or leukemia. Children who didn’t know their parent’s real cause of death was AIDS until after the fact. People who said, over and over, “I’ve never met anyone else”; “I thought I was the only one.”

You are not the only one, we write back. And I am not the only one. This community that’s now 75+ strong has become a makeshift family. Oh, you were mysteriously warned to stay away from your father’s razors? Me too! Oh, your house was peppered with gay signifiers that you were too young to understand? Me too! Oh, you had to nurse your mom on your own at a time when no one even wanted to get close to HIV+ people? Me too! (Well, not me personally, but many in our group.) You had to wade through complicated layers of secrecy to figure out who to tell, and how, and when, and hope they would react kindly? I understand. Even though the stories are wildly diverse, there are so many similarities. Namely: the love for our lost parents, the wish to remember them, the fact that we all battled the isolation and stigma of this disease, the feisty activist desire to keep AIDS in the cultural forefront.

And it’s because of this community of Recollectors that I can join World AIDS Day this year — unequivocally, completely. When “Philadelphia” was released, a year after Dad died, I watched it alone on a VHS tape in the basement of my Mom’s house when everyone else was gone. (Years later, I’d find out that Mom and my brother had watched it alone, too.) I could barely get through it. After that, I avoided most AIDS-related media. This year I sat down to watch “How to Survive a Plague” and thought, This is fine. In fact, this is more than fine. I have a community of people who get it — and now it feels vitally important to catch up on what I avoided all those years. Even though I’m not positive, it’s still our history, too.

Maybe it’s just that I’m getting older; maybe it’s because my family is older, too, and much more supportive now. But I think it’s in large part because of The Recollectors: their grace, honesty, strength, activism and the power of community. Each story is vitally important, and we are so eager to share them all. This year, for World AIDS Day, Recollectors have a private space to talk to others like us, a public space for others to read our underreported stories, and we’re sharing Recollector-themed Six-Word Memoirs all day on Twitter. I’m not under the blankets anymore.

Whitney Joiner is a senior features editor at Marie Claire magazine and the co-founder of The Recollectors, a storytelling forum dedicated to remembering parents lost to AIDS and supporting the children they left behind.

A version of this piece first appeared on TheLi.st @Medium. Republished with permission.