(Gina Meola Photography)

Whenever I meet someone new, they often ask how my name is pronounced and where it comes from. “Ver-jee, like Virginia,” I say. “It was my grandmother’s.”

I’ve had this conversation countless times since kindergarten. On the surface, it’s a simple exchange of basic logistical and biographical information between two new acquaintances. But for me, it’s also an invocation.

I was named Virgie because while my mother was pregnant with me, my grandmother’s cancer was creeping back from remission. By giving me her name, my parents honored my grandmother’s life with mine. She called me “Little Virgie” until she died when I was two. I’ve spent much of my life wondering about this woman who is woven into my identity, but whose death makes her a stranger to me.

My dad rarely talked about her when I was a child, so I collected tidbits of information to compose a mental portrait. As a young woman in the 1920s, she was a teacher in the Kentucky Appalachians, where she rode four miles on horseback every day to reach her students. She was a prolific gardener who loved roses. She was a distant, unaffectionate parent. She wrote beautiful letters.

But no matter how many stories I heard, my grandmother remained abstract to me, like her name was a spell cast over my life. Say a name and sound waves will carry it away on the air. But if you hold something a person loved, it can feel like you’re touching them through time. I needed something tangible to make my grandmother feel real to me.

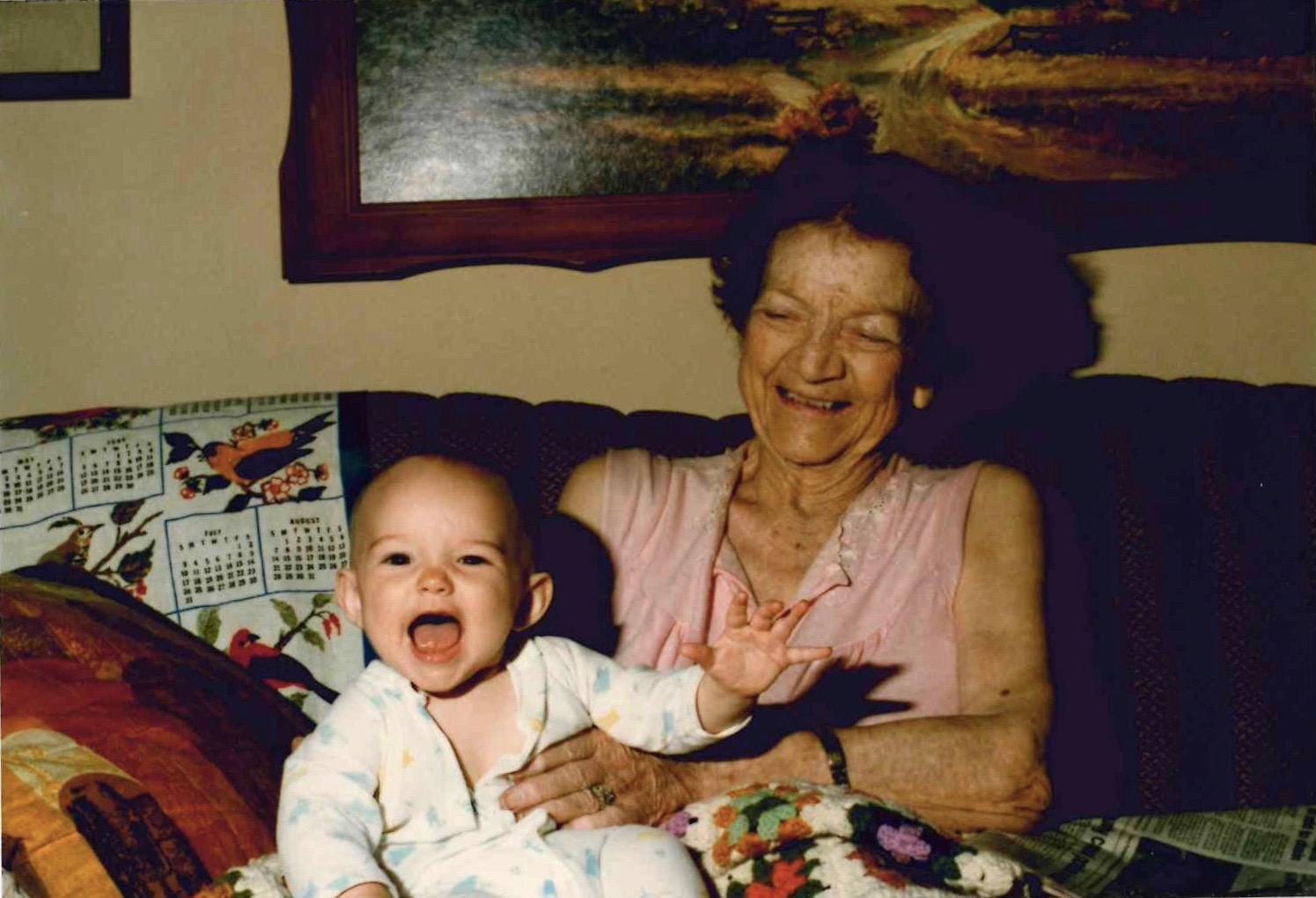

The author, as a baby, with her late grandmother. (Courtesy of Virgie Townsend)

Seven years after my grandmother died, my grandfather fell in his yard and broke his hip. He lay on the ground for hours until an employee found him. He couldn’t live alone anymore, so my family made the long trip from Upstate New York to Central California to sell his house and move him in with us.

I hadn’t been in the house my grandfather had shared with the grandmother I barely knew since I was a baby. I knew that once the house sold, her life there would be gone, too. This felt like my last chance to connect with her. While my parents tied up my grandfather’s business and prepared to sell the house, I went looking for my grandmother.

READ: Is My Necklace an Heirloom? It’s Complicated

My grandparents had kept separate bedrooms for decades. When my grandmother died, my grandfather left her room relatively untouched. Behind a closed door, it seemed forbidden and magical.

As I turned the doorknob to sneak in, the top of my head tingled with apprehension.

Inside, the walls were blue. A photo of her sun-weary father, a Texan rancher, sat on her dresser and her jewelry box rested on a simple wood vanity. Already pushing the envelope of my daring, I wouldn’t rifle through her closet or lie on the blue-and-green print comforter on her bed. Instead, I sat at her vanity and looked at her necklaces.

I picked up her locket, a gold-plated brass oval engraved with a 10-petalled tea rose, and ran my fingers along the border and the brassy wear on the back. I opened and closed it until I worried that the catch would break. There were no pictures inside.

It was the first time that I could remember holding an object that belonged to my grandmother. During our stay in California, I went back in her room time and again to look at the locket. What would happen to it when the house sold? I couldn’t leave it there.

The author’s grandmother, Virgie McAlister Townsend, on horseback in the Kentucky Appalachians. (Courtesy of Virgie Townsend)

As we packed up to fly back to New York, I placed it in red checkbook box and insisted on carrying it on my lap the whole way. Eventually, I fell asleep on the flight and the box slid off my lap. When I woke up, it was gone.

I began to panic. How could I lose my grandmother’s locket already? I had only just found it. I quickly unsnapped my seatbelt and looked down the aisle, worrying that a flight attendant or nosy fellow passenger had taken it from me, the rightful thief.

About five feet away, the little red box waited for me. I scurried down the aisle, snatched up the box, and opened it to make sure the locket was there. It was.

At home, my mom gave me a small picture of my grandmother from my parents’ wedding. In it, Grandma Virgie wears a pink dress and big glasses with clear plastic frames. I cut the photo into a jagged oval and squeezed it into the left side of the locket.

Sometimes when I wear the locket, someone will ask me where I got it and if there’s anything inside. Then I’ll open it to show them Grandma Virgie’s picture and respond, as I have so many times about our shared name: “It was my grandmother’s.” In that moment, she’s real to me.

Virgie Townsend’s writing has been featured or is forthcoming in The Atlantic, The Washington Post, Harper’s Bazaar, VICE, and other publications. Visit her online at www.virgietownsend.com.