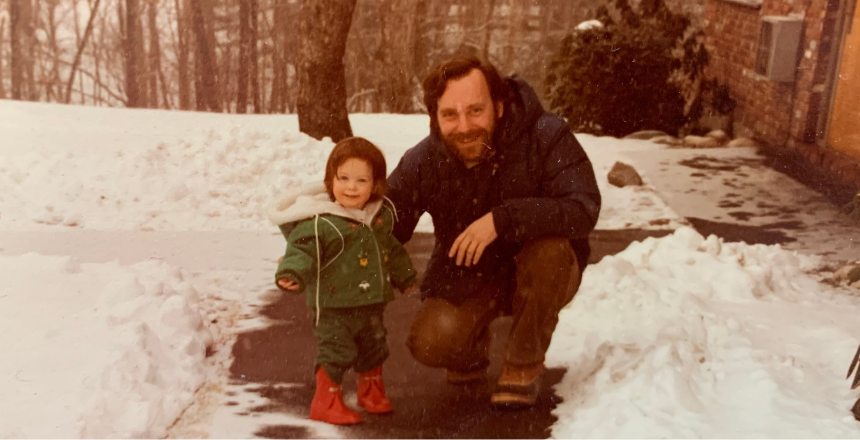

Emily and her dad in Lincoln, MA, 1983

When I was fifteen years old, my father died suddenly in a hiking accident. He left one winter morning for a day hike on Mt. Eisenhower, one of the many peaks comprising the White Mountains in New Hampshire. While on the mountain, he became trapped in a sudden blizzard, grew lost and disoriented, and eventually succumbed to hypothermia. His body was discovered three days later, perched on a rock; his feet were dangling in the stream he’d been following, trying to get home.

It’s common for a present trauma to trigger a past trauma. And I’ve found myself thinking a lot about my father since the pandemic began. Over these last several months, memories and thoughts of his death have visited me more frequently than in recent years. This year in quarantine has summoned many of the same emotions I’d felt back then: fear, anxiety, paralysis, vulnerability. My father’s death abruptly exploded the notion that I or anyone I loved was immune from arbitrary dangers. The pandemic has done this on a global scale.

But I think there’s more to it than that. My past has reasserted itself with a familiar, specific, and undeniable feeling. It’s one I recognize because I know it intimately: the feeling of having been abandoned.

My father was a gentle, comforting and giving person. He was also my idol, my companion, and my frequent hiking partner. We spent many mornings hiking trails in and around Lincoln, Massachusetts, my picturesque New England hometown. I adored him.

He had intended to come home that night. He was an avid hiker with experience hiking in all conditions. He loved me, my brother, and my mother, and would never have consciously put his life at risk. I believe that now, and I believed it back then. But all the believing in the world didn’t change the way I felt. My understanding of his intentions, unfortunately, was irrelevant, because logic occupies no space in grief. I had been wounded on a biological level. My father, the person entrusted with my safety and protection, left the house one morning and never came back. The message I received is that I wasn’t worth sticking around for. And the psychological toll this took was significant.

I spent much of the next ten years in isolation, in and out of mild depression. At the time I didn’t realize any of this, and certainly couldn’t have articulated it; I actually thought I was doing pretty well. I went off to college and outwardly things looked good. I performed well academically, joined a few activities, and had a decent social life.I continued like this, functioning on autopilot for a while, until finally I couldn’t. In my late twenties, my grief at last overwhelmed me. I became lethargic, and withdrew socially. I felt unmotivated to engage in simple activities, and my physical health began to suffer as a consequence. There was no denying that grief had become the dominant presence in my life; it had finally asserted itself in such a way that I could no longer ignore it.

I found a therapist, faced the unresolved grief over my father’s death head-on, and began the process of healing in earnest. And I had a lot of help. Once I turned around and looked for it, help was everywhere. It came in the form of mental health professionals, of friends and family, and of people with shared experiences. It came in the smallest exchanges: an old friend who reached out on the anniversary of my dad’s death; a stranger who smiled warmly on the street. It came in the form of simple human kindnesses.

We are a nation that until recently enjoyed the luxury of feeling comfortably removed from suffering felt elsewhere. But from the beginning of this catastrophe, our previous leadership exhibited only a callous indifference to our lives and remained tragically devoid of any and all characteristics that a decent father might possess: compassion, empathy, generosity. Month after month, we received one clear and consistent message: You’re worthless. Not only was there no help, there was no concern. No words of comfort, no promise of better days ahead; no acknowledgement, in fact, of our collective loss at all.

A few months into the pandemic, I noticed that I’d begun to function on autopilot, numbly experiencing the day-to-day effects of this slow-motion trauma. We are a population abandoned, for nearly a year, by the people charged with its safety. It is an easy thing to downplay or dismiss. Still, logic occupies no space in grief. And the transparent and malicious disregard for our health and safety takes an enduring psychological toll. All the knowing in the world doesn’t change the feeling abandonment provokes.

Thankfully, there is light ahead. We have new leadership, exhibiting at long last genuine compassion and empathy. This pandemic will end. And when it does, our nation will at last have the opportunity to grieve. It will also have the opportunity to heal.

We are a community. One united – if in no other way – in the shared experience of this trauma and loss. And we can be for each other a collective source of purpose, of hope, and of peace.

And help is still everywhere. It’s in the massive majority of people for whom love, generosity, and decency remain guiding principles. It’s in the people who work tirelessly on behalf of others. It’s in the friend who reaches out to ask how you’re holding up; the stranger who pauses on the street so your young daughter can pet her dog. If my own experience with grief has taught me anything, it’s that we are not an aggregate of individuals. We are a community. One united – if in no other way – in the shared experience of this trauma and loss. And we can be for each other a collective source of purpose, of hope, and of peace.

My father would have turned 75 this January. I spent his birthday this year as I often do, hiking along one of many quiet mountain trails in Southern California. I couldn’t hike for many years after he died; the memories were too painful. These days, I hike a lot. It is an activity I cherish, and one I’ve felt particularly grateful for these months, as it allows me to follow that familiar human impulse of responding to trauma by escaping into nature.

I choose a route that offers an expansive view at the summit. I leave in the early morning and hike to the top, pulling my soft hat over my ears in the chilly January air. I gaze out over a stunning vista, past miles of forest stretching all the way to the ocean. I see a world breathtaking in its natural beauty. I see a world full of possibility, and of promise. And I see my father everywhere.

Emily Halpern is a screenwriter. She lives in Los Angeles with her husband and two-year-old daughter.