Throughout my twenties there were more times than I can count when I found myself in a situation that made me think, “This would not make my mother proud.”

In nearly every one of those instances — whether in the basement of a lager-soaked Lower East Side bar, a conference room where I’d just sworn cattily at a co-worker or behind the wheel of a rental car I’d lightly crashed thanks to one of my four-inch heels getting squeezed between the brake and the accelerator — the next thing that crossed my mind was the same.

“She’s gone now. So it doesn’t matter.” As I approached 30, my state of suspended adolescence lurched onward.

I never believed my mother wasn’t flawed. Like most teenagers and young adults, I tended to disagree with her, often to the extent of tearful journal entries and screaming matches that left me slamming the door of my bedroom behind me.

But she was, unquestionably, calm and methodical and disciplined, an astute list-maker with handwriting that looked like it was straight out of a 19th-century calligraphy school. I, on the other hand, was impatient and sloppy, easily distracted and eager to push the boundaries my mother calmly told me were there for a reason.

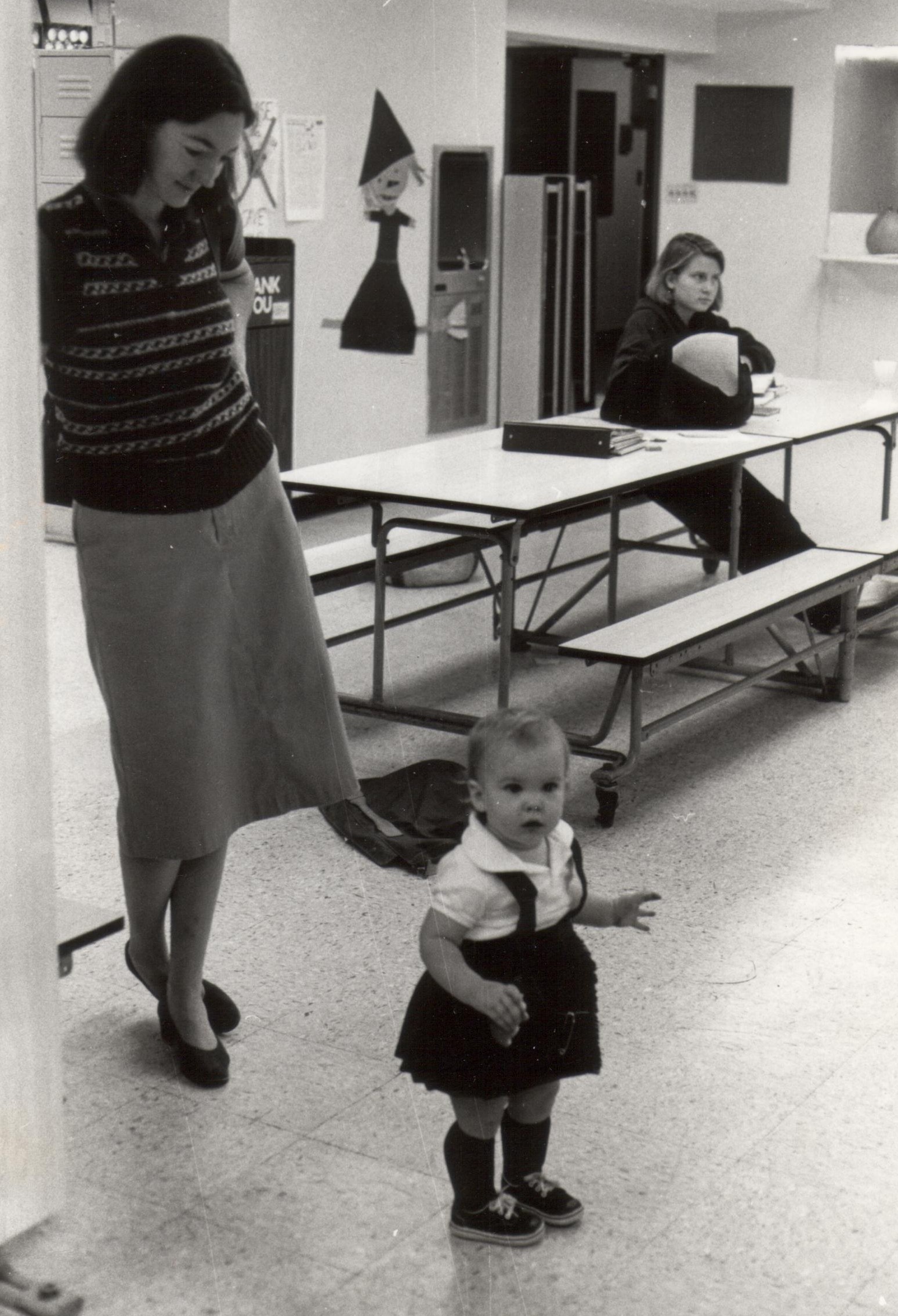

Her demeanor was “Downton Abbey”-refined. I spoke in constant staccato, bug-eyed behind thick horn-rimmed glasses, with the sense of humor of a writer who dreamed of working for “The Colbert Report.” My mother was the one who could tell me when I should keep my eccentricities to myself, who gradually ironed the “ums” and “likes” from my speech, who assured me the rapid-fire, aggressive nature of my brain could be a powerful asset if I could only learn to rein it in. She taught me the value of the comforts of home, even if I didn’t always think there was anything to it. Her idea of leisure was reading a good book in the backyard. Mine was tramping around in the woods.

As I grew older, I like to think that as I matured our relationship shifted to one of two adults, my mother and I were beginning to see eye-to-eye and gain a mutual respect for one another. I never found out whether this would actually happen. She died of breast cancer when I was 23.

At the time, I was teetering somewhere between the sweatpants-and-flip-flops college days and the early years of a career in media — between Ikea and West Elm, between Bud Lite and pinot noir. I don’t remember much about the days, or even weeks, after her death. My energy levels spiked, as though some enzyme in my mind had gone haywire from such an intimate reminder that we don’t, in fact, have all the time in the world. I remember sitting alone in the car in a parked suburban parking lot, playing the manic rhythms of an “Against Me” CD at full volume and quietly freaking out over the fact that I was caught between two parallel but conflicting emotional states.

“Nothing is holding me down anymore, and I can do what I want now.”

But also: “Nothing is holding me down anymore, and I don’t know where to go now.”

Subconsciously, I was scrambling to find a silver lining for my mother no longer being there as both moral compass and homing beacon. But I was really spinning in no particular direction, and it scared me. If I was distracted before, now I was just plain flighty and distant. I was a self-involved career drone. A commitment-phobe who fled romantic relationships as soon as meeting the family happened. Sometimes, thanks to my telecommuting-friendly work in digital media, I’d just up and disappear for a month. I was shocked when friends’ wedding invitations arrived in the mail; I’d stopped expecting that anyone would even invite me.

When I lost my mother, I tried to take on the world while not really participating in it. The grand result: I maintained a sort of permanent teenage mentality. By my late 20s, I’d never signed an apartment lease, owned a car, or purchased anything as domestic as a set of cutlery. I’d begun to speculate that I wasn’t particularly likeable.

It was going to have to stop, somehow.

The thing that my mother and I had most in common is that we derived immense satisfaction from challenging, diligent work. She’d refused to take a leave of absence even as cancer treatments took an increasing physical toll on her, and she’d discouraged me from scaling back my own work while she was sick. She ultimately died over the Thanksgiving long weekend, and during the memorial service my father joked she’d timed it so that no one would miss any work or school.

And so, perhaps it was fitting that when I finally learned how to stop stumbling manically through life, it was revealed to me through my professional life. In 2013, I started freelance consulting after a job at a start-up didn’t work out. At first, this was thrilling. I could work in pajamas. I could poke in and out of client work, not needing to see the same people too often, and I could travel more than ever. But in the end, this pushed me over the edge. I was rootless. I couldn’t handle this lifestyle. I needed stability, and for the first time this was tearing at me enough that I was willing to take the initiative to figure it out myself.

And, thanks to both happy coincidence and a newfound willingness to put my trust in other people, I had both a job and an apartment by early 2014. I stopped thinking about whether whatever I was doing would meet my mother’s approval or disapproval, and started focusing on learning from what she’d do in each unfamiliar situation.

Of course, I still wish I could call my mother whenever I’m overwhelmed or bewildered. I still wish I could have seen our relationship make its full transition to one between adults. I think about how much she would have loved every role that Maggie Smith has played in the past decade, and how much I would have liked her to meet my cat.

But most of the time, I’m reassured by the tacit understanding that what would have truly made her proud is to know that, at long last, I can stand on my own.

I’m getting there.

Caroline McCarthy is vice president of communications and content at advertising technology company true[X] Media, and a former print and TV journalist. She lives in Brooklyn with her cat, Caterpillar, in an apartment where she finally has a dishwasher and a name on the lease and other adult things.