Early morning light streamed into the family room, creating the sunny cheerfulness that most people seek out in a new home. Not me. Incensed that my parents hadn’t yet found curtains for the bay windows, my younger brother and I entered the room like little vampires, with squinty eyes and arms flung around our heads trying to create some protection from the sun.

The TV, placed directly across the room, emitted sound, but the picture was completely obliterated by the blaring light. Unable to watch my beloved Saturday morning cartoons, I ran into the kitchen, trailed by my little brother. My mom stood amid a mountain of boxes, unpacking the china.

“Go outside and play,” she offered as an unwelcome solution. Whether or not we could watch cartoons was the least of her worries.

It was the early 1970s and my dad was dying of the autoimmune disease Lupus. Most days he went to work, business as usual, and came home in time to kiss us goodnight. But occasionally there were scary moments like the time he fell over in our yard, or the night he was rushed to the hospital while we were sleeping.

His impending death was an unspoken evil lurking in our house, something we knew would some day ruin our lives, like a poisonous gas slowly seeping in through the floorboards. We all looked for ways to comfort ourselves: my mom, about to be a widow in her late 30s with three children under the age of 11, sought out fortune tellers who offered up a better future; my older brother escaped to friends’ houses where everyone had a clean bill of health; and my younger brother and I turned to television with its soothing imaginary storylines that always turned out well.

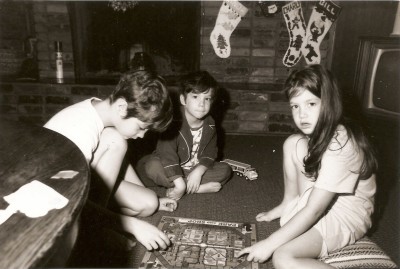

Our addiction was becoming an ever-growing beast and inspired invention. Rather than accept defeat, we scurried from the kitchen, stripped the blankets off our beds, took all the cushions from the couch, pulled the end tables away from the furniture and started building a fort around the TV. We crawled inside this now wonderfully dark room where our cartoons blazed in all their glory and we were only seen again when it was time to eat.

Related

“Underdog,” “The Jetsons,” “The Pink Panther,” “Josie and the Pussycats,” and “Around the World in 80 Days,” bled into “The Price is Right,” “Let’s Make a Deal,” “The Dating Game,” and “Hollywood Squares.” We became adept at guessing the value of a washer/dryer or a dinette set. We weighed in on which dates a bachelorette should pick. We got annoyed when actor Charles Nelson Reilly’s answers were too crazy and the contestant lost the middle square. When the boring evening news came on, we crawled out, pale and disoriented for dinner. But after dessert we scrambled back in for sitcoms and variety shows until bedtime when we were pulled out, kicking and screaming like newborns.

The fort stayed up for weeks. My mom had never known such quiet, such peace from her children. There was no fighting, no quarreling, no name-calling. We submissively climbed into our fort like little mice going into a cage and didn’t re-emerge until called to the table for meals.

As the days wore on, real life sounds became harder to hear. We plunged deeper into the tube where a parent’s voice was no match for Carol Brady’s or Bob Barker’s. No one answered when my mom asked for help, maybe to set the table or feed the cat, I can’t quite recall. But this failure to respond had dire consequences: We had to tear down the fort and were banned from watching TV. Blinking back tears, we pleaded for another chance. There was no pity in her stony Irish gaze. Miserably, we disassembled the fort and put the furniture back in place.

Days and weeks of mindless entertainment had turned our brains to mush. The next day my brother and I sat next to each other on the couch and stared at the blank TV screen. We sat there passively until our mom walked in and gave us a withering glance. “Pathetic,” she said, then walked back out of the room.

The shock of losing the TV fort paled in comparison to my father’s death, but this first loss was a preparation for that inevitable, devastating moment. Boredom, and then curiosity, eventually led me to the back door of the house, then out into the yard where I learned how to climb trees and whistle, to barter a baloney sandwich for peanut butter and jelly with the neighborhood kids, and somersault down a grassy hill landing in a heap where I stared up at the clouds.

Sometimes I still allow myself back into the “fort.” There are days when I am unable to tear myself away from the couch as I gorge on TV, basking in other people’s dramas while mine remain safely outside the apartment door. Yet it’s only a matter of time before I’ve gathered my strength and summoned the courage to head back out into the world, confident that my dad has my back.

Linda Perkins is a filmmaker, writer and storyteller living in New York City. Her latest project, 37 Vibrations, explores the healing effect of love stories traveling the world as message in a bottle. She’s on Twitter @37lovestories.