Zafar saw something in me that I certainly didn’t. He was my big brother, three and a half years my senior, charged with the energy of a Labrador puppy and possessed a frustratingly superior intellect. He was an economist with the Treasury, where he was beloved.

He also had brain cancer, which we learned around two months before he died.

I was 22 years old at the time, and he 26. I was a college dropout, with no real prospects, not a lot of confidence and intermittently crippling Fibromyalgia. In short, my future looked somewhat bleak long before Zafar’s death.

My mother had herself almost died from cancer a few years before Zafar did and I became a part-time student to take care of her. By some miracle she survived, but then not long after that my chronic Fibromyalgia began to set in. That’s when my path to getting a university degree really began to derail. I dropped out of classes three semesters in a row.

READ: Grief Bacon — Mourning My Mom, and My Figure

Even as he faced death, Zafar would only let me face life. He all but mandated I apply to Columbia University, which offered a program specifically for students with unorthodox circumstances. I resisted, insisting I wasn’t smart enough for an Ivy League school. He insisted, resisting my “ridiculous” protestations — and proceeded to ban me from visiting him in the hospital until he was satisfied with the progress I was making on my application.

Even as he faced death, Zafar would only let me face life. He all but mandated I apply to Columbia University, which offered a program specifically for students with unorthodox circumstances. I resisted, insisting I wasn’t smart enough for an Ivy League school. He insisted, resisting my “ridiculous” protestations — and proceeded to ban me from visiting him in the hospital until he was satisfied with the progress I was making on my application.

Everyday, he would give me a to do list. “You’re not allowed to come to the hospital today unless you have a first draft of your personal essay done,” he threatened. I immediately went home and dashed something off to return as quickly as I could. “Let me read it,” he said as soon as I arrived, only to tell me it was shit. “Go back and do it again.”

This went on for a few weeks until he was satisfied with it, at which point he oversaw my submitting the application, down to paying the fee. October 15, 2008, the day my Columbia application was due, was the last time I saw him before he became brain damaged.

A little over a month later, he was declared brain dead. We were waiting for an OR to open up so the surgeons could harvest his organs, which he’d opted to donate. The hospital was artificially keeping him alive until then. When the nurses finally arrived to wheel away his bed in the early hours of the morning, they took with them the only world I knew.

Zafar truly exemplified what it means to live life to the fullest. We were bopping around in the sea on vacation once and looked on in awe as a boat whizzed past, a parasailer attached to the back, cutting through the sky. Next I knew, I was getting strapped into a parachute harness. He’d also somehow managed to rope our risk-averse parents into the adventure. Fundamentally, he saw life as a set of opportunities just waiting to be seized. And it was always done with a sense of humor.

A few weeks after he died, I was invited to interview with Columbia. The day after the interview, they called to say they’d unanimously admitted me. I wanted to pick up my phone and call Zafar. Classes began four weeks later and I never dropped out again, even when my Fibromyalgia was so bad I could only manage one class a week.

I felt like Columbia was Zafar’s parting gift to me, to get my life back on track and I was so stubbornly motivated by his death, I vowed to actualize the life he’d envisioned for me: one of success.

READ: The Long Arc of My Mentor’s Impact

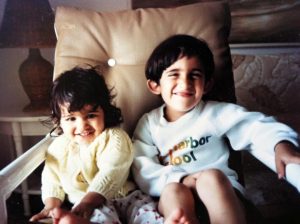

Little Natasha and Zafar

Before his thrilling transformation to civil servant, Zafar had worked at a newspaper in Pakistan for a year. After I graduated, I followed his footsteps to work there, too. When he lived there a decade earlier, it was stable, for the most part free of radical Islam. And in the intervening time the country had descended into volatility and extremism.

As he would encourage me to do, I made the most of life’s difficulties there. I went on a lesbian Tinder date with a woman whose father had been kidnapped by the Taliban for ransom. I later turned the experience into an acclaimed one-woman comedy that I took to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. Zafar’s “you only live once” approach propelled me to stage the play. And all of my unusual work experience eventually led to the dream job at Mic that I always wanted.

Admittedly, I have no counterfactual experience to a world in which Zafar lived. And part of my transformation is invariably due to my growing up: I write this as a 30 year old. But I know that all the major — and many minor — decisions I’ve made since he died have been motivated by the desire to make him proud. And I am, without doubt, a better person for it.

Natasha Noman is a News Staff Writer at Mic, with a focus on global affairs. She has also reported on regional affairs for the Friday Times (Pakistan) and is a playwright and performer with an acclaimed show, Noman’s Land, which premiered at the 2015 Edinburgh Fringe Festival.