Every year, I fail to observe my father’s deathiversary. I am usually reminded of it when my sister tags me in a picture on Facebook. She’s so good. Hawaiian Asian daughters are expected to visit their dead on special occasions like birthdays, holidays and the anniversary of their passing. They bring a watering can to fill at the spigot so they can wash the dust from the headstone. They pull cobwebs from the vases in the ground and fill them with fresh flowers from a roadside stand. They say prayers. Sometimes, they bring a picnic lunch.

Related

When I was growing up, I never thought it strange to go on an outing to the graveyard to have lunch with my dead grandparents. The memorial park is breathtakingly lovely — rolling green lawns with a winding stream and koi ponds. We always made sure we had a bag of stale bread to feed the ducks and fish. My favorite part of the park was the section called Babyland, where the graves had pinwheels and balloons, and sometimes tiny shoes or toys on top of the stones.

If you faced inland, soaring cliffs shot straight up into the clouds. I loved to lie on the grass and watch the hang gliders taking off from the summit. My dad told me that sometimes they crashed into the rocks, but I never saw one do that. They just wheeled and turned and somersaulted like lazy butterflies. If you turned the opposite way, you could see Kāneʻohe Bay opening out into the Pacific. The day of my father’s burial, I stared out at the ocean and listened to the shots fired by the honor guard soldiers echo off the Ko’olau mountains.

I live in California now, and the land is flat and mostly brown. My trips back to Oahu never coincide with visits to the cemetery. I could go if I wanted to, but I don’t. I take my children to the beach and the shave ice stand and my favorite malasada bakery. This is as close as I get to a pilgrimage: once, we drove to my childhood home and I showed them where the pua kenikeni and plumeria trees used to be before the new owners cut them down. I told them how their grandfather spent hours in that yard, happily and methodically digging out clumps of nut grass and milkweed with a forked metal tool. He could spend an entire afternoon on three square feet of grass. I think he worked slow on purpose. I didn’t know the word “meditation” when I was a kid, and anyway, we were Catholic, but now I understand that this was his.

When I see the pictures of my smiling baby niece crouched over her Papa’s grave and the beautiful cut flowers my sister and her husband have neatly arranged, I feel the sting of guilt in my throat and behind my eyes. I’m not doing the rituals. I don’t offer up a prayer. I don’t mourn on the customary days. I resist. I have never grieved my father the right way. This, I am sure, would both annoy and please him.

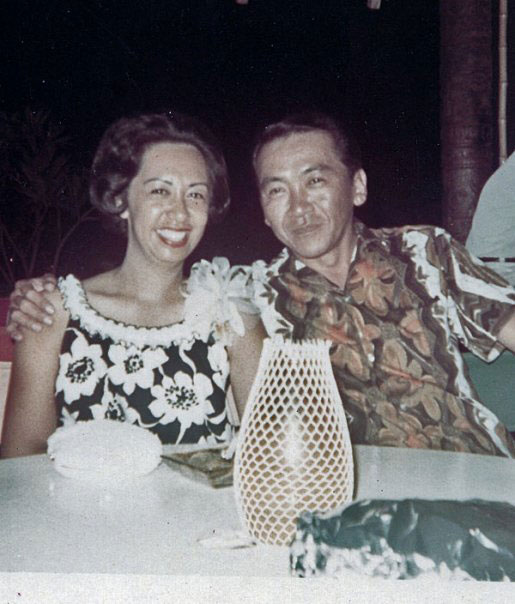

He gave me my cheekbones, my brows, my button nose, my hot temper, my hard head, and my smart mouth. I fought with him because he understood me best. He would get my refusal to conform.

Instead, I tell funny stories to my daughter about the grandfather who died when she was growing in my womb. I eat a slice of lemon meringue pie and wash it down with black coffee the way he would have.

The other day, I opened the door to my father’s face and for one insane second, I couldn’t feel my body. My head bobbed, weightless. Maybe there was a dimensional rift right there on my front step. Then, he smiled and his face changed back into that of my uncle, who was in town, there to pick up my mother for lunch. I introduced him to my daughter. “This is your Papa’s brother.”

“Do I look like him?” he asked.

She frowned, confused.

“She never met him,” I said. “He died while I was pregnant.”

“Oh,” said my uncle, with a touch of sadness.

That night, I sat on the floor of the shower and sobbed into my hands for half an hour. Afterward, I felt sore and clean, like you do after a hard workout.

Would I feel comforted if I went to my father’s grave? I don’t want to eat a sandwich on top of his moldering bones. When I let go of my traditions, I didn’t put anything else in their place, so what I have now are memories that wheel crazily about with colorful wings. Once in a while, they crash into the side of the mountain and I am temporarily destroyed and awed by their beauty.

Nanea Hoffman is the founder and Editor in Chief of Sweatpants & Coffee. Her work has also appeared in Role Reboot and The Washington Post.