I didn’t cry at my father’s memorial service, packed shoulder to sweaty shoulder into an old barn on the outskirts of Reno. I didn’t cry when the barn doors flew open and a dozen of my father’s motorcycle buddies revved their Harleys in a howling display of honor and grief.

I didn’t cry when we scattered his ashes under an evergreen tree with its branches all catawampus at the top, a quirk that reminded my mother and me of my father’s bedhead. I didn’t cry when I got my learner’s permit and took my father’s beloved, silver sports car out for a 100-mph joyride, days before my mother sold the car. I didn’t cry on a Tuesday morning in September, when I turned on the TV to find one half of the World Trade Center on fire, a single matchstick burning on the small screen. I didn’t cry when the weight of humanity seemed to sprinkle over my fifteen-year-old shoulders as the North Tower fell. Loss is loss is loss. No matter the circumstance.

I didn’t cry when my mother and I both shrunk into five-feet-tall figures of hips and bones, subsisting on nothing but deviled eggs my grandmother delivered by the dozen. I wanted to run to my mother. And run away from her. I wanted to press fast forward or rewind and send us forward or back; it didn’t matter as long as we weren’t there. When I saw my mother’s red and swollen eyes, I knew I was powerless to help her. So we danced around each other, co-existing in a haze of involuntary life. Sometimes my mother slept all day and sometimes she didn’t sleep at all. Sometimes we hugged each other in the hallway. Sometimes we didn’t acknowledge each other. Mostly, she was out of the house dealing with the logistics of sudden death. My parents owned a collection agency together, so my mother didn’t just have to manage the loss of a husband, but a business partner, too. When she went through my father’s office, she found a stack of recently organized folders containing documents, account numbers, and passwords only my father knew. She wondered if he knew he was sick, but didn’t tell her. I didn’t cry when she asked me what I thought. It didn’t seem to matter either way.

I didn’t cry until one fall afternoon, when I pulled a knife out of my flesh. It bored so deep into the fleshy space between my thumb and forefinger, that when I lifted my hand from the apple I’d been steadying, the knife held its place like a sixth appendage. I looked at my polydactyl hand for a few moments, perplexed because I felt no pain. When I grabbed the wooden handle and yanked, no blood appeared, so I steadied the apple again and went in for a slice.

Then it came, pouring out from deep within the centimeter gash, falling down my forearm, and soaking the half-cut apple. I grabbed the nearest dish towel and held my hand over the sink. When I lifted up the towel to check the wound, blood erupted like magma finally released after eons trapped by the pressure of Earth. By the time I picked up the phone to call my mother at the office and insist she come home, the dish towel was slick with red.

My mother found me fifteen minutes later, curled over the sink, sobbing into a puddle of blood. I howled as she wrapped my hand in a new towel and led me to the car. The wound was narrow, but the cut went deep. When I looked at it on the way to the urgent care, my mother had to pull over to let me throw up on the curb. I threw up again in the waiting room, and the nurses carted me away because my hysterics disturbed the rest of the patients.

“I’m going to need her to calm down,” the doctor said to my mother as he handed me a barf bag and prepared to stitch me up. “It’s only one stitch. I don’t understand what the problem is.”

I turned my head away from him and continued to sob, embarrassed and unable to catch my breath or hold still. A nurse caught my eye and glared at me while she washed her hands, organized boxes of gloves, and scribbled across my chart.

“Her father just died,” my mother snapped. “It’s not about the stitch. She’s fifteen. Give her a damn break.”

The doctor adjusted his glasses, grabbed my bloody hand, and muttered in a softened voice, “I’m sorry to hear that. I promise I can do this quickly, but you have to relax.”

He slid the suture through my skin, fusing the severed flesh back together again. I felt the wiry thread pull deep within me as he tied a single knot, willing myself to be less space while my mother held my good hand, tears filling her eyes as she whispered, “I know, honey, I know. It’s okay. It’s okay.” I kept still, wishing I could disappear from the impatient doctor, the leer of the nurse, and the heartbreak of my mother. When the doctor snipped the stitch and backed away, I gasped for breath, then puked.

The scar was still thick and tender a few months later. I ran my fingertips across it during my first appointment with Dr. Sanders, a child psychologist my mother insisted I see. She was a pale and plump woman who, against her office’s mahogany floors, struck me as a polyp invading deep, rich skin. I wanted to scratch her out of my existence before she opened her mouth. I was a teenager with the internet. I knew from before I set foot in her office that I was dating anorexia and having the occasional affair with bulimia. I was ripe for a clinical diagnosis.

I also knew that even if I whittled down forty pounds of skin and bones, I would still take up space. Even in death, I would take up space, either in the form of a six-foot-by-four-foot plot of land or in ashes stuffed into a twelve- inch-by-eight-inch pine box that would live in the closet right next to the twelve-by-eight box that contained all the space that was once my father. No amount of shrinking could erase the space.

So I talked.

“I think I have an eating disorder,” I told her. “Why do you think that?” Dr. Sanders asked.

I listed off my various peccadilloes, punctuated with references from my hours spent scrutinizing the holy grail of fucked-up brains, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Dr. Sanders sat for a moment and looked at me, taking in the first bits of information I offered up.

“You know,” she said, “I had another client once, and she only ate things that were white. White bread, white potatoes, white corn. Now that’s a real eating disorder.”

From that comment on, I shut down like a union worker on strike. My mother dragged me to session after session, but instead of talking, I stared over Dr. Sander’s head, grunted, and took loud, dramatic breaths whenever she asked me a question. In a last-ditch attempt to get me to say something, she pointed to a feelings poster hanging on her wall, with a series of cartoon faces all scrunched into expressions like “irritated,” “furious,” “confused,” and “ashamed.”

“How are you feeling today?” she said, almost begging for a response.

I cocked my head sideways, feigned a good look at the poster, and said, “Where’s the face for, ‘This is a waste of my fucking time?’”

Dr. Sanders, apparently, agreed. She diagnosed me with an anxiety and depressive disorder and told my mother that she was wasting her money on a psychologist because what I really needed was a psychiatrist. I didn’t argue. All I wanted was to be left alone, to be less space.

A few days later, I was in a psychiatrist’s office, watching him skim my chart.

“You’ve been through a lot,” he said. “Let’s see if we can help you with that.” He wrote me a script and told me to call him if I experienced any of the side effects listed on the pamphlet.

The first prescription made me nauseous and I sent myself home from school. Back to the psychiatrist and onto the next drug. That one put me to sleep, so we tried another, but it made my heart pound and my mind race.

We stopped that one and tried two more. After a few weeks, I told the doctor my hair was falling out, and he referred me to an endocrinologist. Later, I told him my stomach burned, and he referred me to a gastroenterologist.

By the time school let out, a cocktail of new prescriptions pulsed through my veins.

“How do you feel today?” the psychiatrist asked at a follow-up.

“Fine,” I said.

At our check-in, one month later.

“How do you feel today?”

“Fine.”

Two months later.

“How do you feel today?” “Fine.”

Six months later.

“How do you feel today?”

“Fine.”

“Come back if anything changes.”

“Fine.”

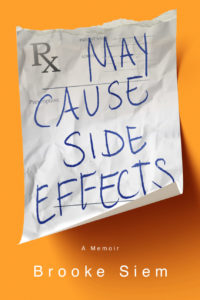

Excerpted from May Cause Side Effects by Brooke Siem