(123RF)

The teenage girl who survived kidnapping and sexual assault to become a crusader for online safety. The pioneering physician who helped start the street medicine movement, treating the homeless where they are. The dying college professor whose last lecture taught the world how to live.

For years I worked as a journalist, and it was my job to tell other people’s stories.

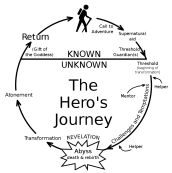

The stories I told often followed a similar trajectory. Regardless of where the protagonist in those stories begins their journey or the nature of their quest, they follow what’s known as the hero’s journey — a kind of storytelling that propels the world’s most popular books and movies. The writer Joseph Campbell described it like this:

“A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered, and a decisive victory is won: The hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

(Wikimedia)

Sound familiar? Think Telemachus leaving his island in search of news of his father, Moana leaving her island on a journey to save her people, or Luke Skywalker leaving his home planet to learn the ways of the Force and overthrow the evil Empire.

READ: The Pittsburgh of My Dreams

I work for a campus organization now, and for the past three and a half years I’ve been teaching college students how to find their voice, how to tell their stories. In doing so, I’ve taught the hero’s journey because I believe it is ideally suited to telling student stories. Many of the college students I work with are far from home. They are taking their first steps into a larger world.

As time goes on, I find that teaching the hero’s journey makes me sad and frustrated, because I cannot complete it in my own life. Because the hero, in the end, must defeat, persuade or gain the approval of the father, the “initiating priest” through whom the youth passes into adulthood.

My own father died by suicide during my junior year of high school. I had no warning, no intuition this was about to occur, and thus no opportunity to confront or save him.

As the years have passed since my father’s death, I have achieved goals that I thought would allow me to feel like I had passed into adulthood. I finished college and graduate school. I became a lawyer and tried court cases. I ran a newsroom. Three years ago, I got married.

And then, two years ago, I had a son.

Now, as I take up the role of a parent, I feel like I have passed the final trial.

I cannot rescue my father like Luke Skywalker, nor fight at his side like Telemachus. But I can merge with the archetypal father. I can become the father, and in doing so complete my hero’s journey on my own terms.

Campbell taught that every hero returns from their quest with wisdom they are meant to pass on to others. I am that mentor now. And when I have taught my son enough, and he reaches the age of the heroes of myths and movies, the age of the students I teach, he will begin his own hero’s journey and take his first steps into a larger world.

Geoffrey W. Melada, a former lawyer and journalist, lives and writes in Washington, D.C. This is his second piece for Modern Loss.