During the summer of 2015, I lived in San Francisco. I was an intern in CNBC’s new office; my dream job in a dream city.

But instead of just getting to know San Francisco — exploring its fog-filled landscapes, getting to know the different artists and techies and eating my weight in burritos — San Francisco got to know me and my grief.

It’s 7:15 a.m. on Monday, on San Francisco’s Muni 1AX bus route. I start crying. It’s 4:30 p.m. on Tuesday after work, and I’m sitting on Baker Beach with a burrito. I start crying. It’s 2 p.m. on Fourth of July weekend and I’m driving on I-5 to an L.A. suburb to see a friend from summer camp. I start crying.

Anytime I thought about talking out loud that summer, I cried. I’d walk to the grocery store after work and would cry while looking at produce. I’d abandon plans to drink a beer and catch up on “The Daily Show” with my friend from college and her family, who I was living with. I’d set up dates and movie plans and then ghost everyone an hour we were to meet up.

And yet, I was the happiest I’d been all year—alone with my feelings and free to do what I wanted.

***

It’s January, 2015. I’m 20 and in the beginning of my junior spring semester. My mom calls and asks if I’m alone. Then she tells me the news: My biological father is dead. I don’t respond right away, and when I do, I only say “Alright,” and hang up the phone.

Ten minutes later, I’m in tears. I can’t even get the words out to tell my partner without crying. He holds me for five minutes before I can finish the sentence: “My father is dead.”

I find my little pink stuffed animal puppy, hold her, and cry some more. That pink puppy was the only thing he ever gave me, and he gave it to me the last time I saw him, half a lifetime ago on my tenth birthday.

READ: Complicated Grief: How It’s Different

Soon, my grief doubles. That same partner—my first love—walks into my room ten days later and reads off a list of reasons why we need to break up: “I’m just not feeling this whole monogamy thing anymore.”

I ask “Why now?”

“There’s never a good time to do this, Sam.”

We’re both living in our co-ed Greek house, so we set up new boundaries. He agrees to them — Don’t bring dates back to the house. Don’t get involved with people in our house. Avoid talking to each other — and then breaks them without remorse.

In our final month living together, he spirals. He says he feels like he has control over me. He never loved me, he says, and doesn’t want to be emotionally responsible for me. He breaks a chair in front of me while we’re talking.

My last straw comes at a fraternity reunion. I’m high for the first time and laughing at a joke. He dashes out of his bedroom, pulls me aside: “I need you to leave the living room because your laughter is literally filling me with rage.” His hands tremble in the same way they did two years earlier when he tried to punch a brick wall..

I exhale.

I pack an overnight bag. The next day, my mom tells me to crash on someone’s couch for the rest of the semester and keep my bedroom door locked when I’m home. I listen. After all, she knows what abuse looks like.

***

When I come back from a summer in San Francisco, everyone asks questions: Did you love it? 100 percent. Was it everything you ever wanted? And more. Did you make any new friends? I didn’t see the point.

The last one leaves them scratching their head. It feels obvious to me: Like my favorite red wines, grief needs to breathe. Three months in San Francisco served as my deep exhale.

My solo museum trips, my excursions to Baker Beach to cry into my burritos, my late night dance parties in the pool house I was crashing in. They all taught me how to love myself again. Grief and loss and abuse are isolating. Still, my trauma brought out an untapped strength. To take on grief, I reveled in the isolation.

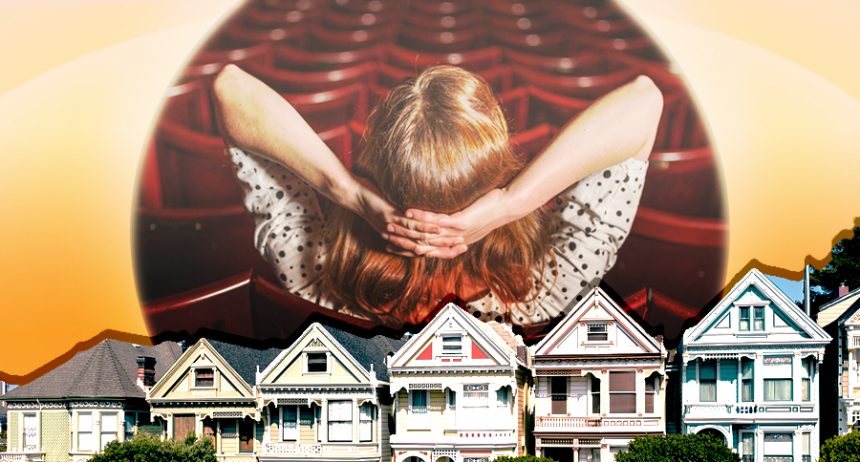

That same summer, “Inside Out” is released. I decide to go alone. I sit in the nearly empty theater and notice everyone else brought company to share popcorn with. The movie starts and my popcorn is nearly full as the main characters—emotions inside the head of a preteen girl—begin to unfold.

That’s when I cry, again. But instead of crying for normal, grief-driven reasons, I’m crying because I’m hearing what I need to remember. For most of the movie, the other emotions are trying to block out sadness because really, who wants to be sad when you can feel joy or anger?

READ: The Best Show for Your Grieving Child (and You)

This preteen girl wants to be sad, though. I cry because I, too, want to be sad. That’s when I realize I’m crying because I’m proud. I’m proud because this summer let me ignore the temptation to invite other people to see this movie. I’m proud because I ignored the societal pressure to always be socializing. I’m proud because I had found a way to grieve and heal.

I’m proud because I had finally learned how to listen to myself, and it feels great.

Sam Sabin is journalist, radio producer and Tar Heel living in D.C. You can find her either working on her new serialized podcast about what she did the year after her father died (“Good Grief”) or at your local Wendy’s.