When I was 15, I came home from an overnight stay at my cousin’s to find my sobbing grandmother in our living room, surrounded by my aunts. My grandfather gently touched my shoulder and motioned me into the hallway to offer an explanation.

“Your Uncle Billy died the other night,” he said. “Overdose.”

I went back into the living room and grabbed my grandmother’s hand, the one not shakily smoking her seventh cigarette of the morning.

“I’m so sorry Nan,” I told her.

She went on weeping, locked in the prison of her own grief.

Prison is something with which my family is intimately familiar. One of my earliest memories is going with my grandmother to visit my Uncle Billy during one of his shorter stints at Rikers Island correctional facility, where he was doing time for robbery. I was about 4, and remember him picking me up for a hug and me petting his platinum bangs, smoothing them down flat on his forehead.

“What am I, your pet?” he teased.

“Yes!” I answered. “You’re my pet Billy goat.”

“Baaah!” he brayed, to my squealing delight.

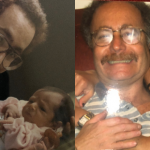

My Uncle Billy was my mother’s older brother, as well as my godfather by baptism. He was also the closest, most consistent father figure of my early childhood years — a stand-in parent and a pal. He would sit with me watching “Wizard of Oz” for the umpteenth time or jam with me for hours on my toy instruments, banging manically on a tiny tambourine while I whistled into a plastic harmonica.

Related

It was my uncle who put an abrupt stop to the beatings I had endured for years at the hands of my stepfather. Even before he had married my mother, my stepfather had developed the habit of hitting me whenever I did something he deemed disrespectful — refusing to call him “dad” because I said I already had one, forgetting to say grace before my first bite of dinner, or accidentally omitting a “please” or “thank you” from a request.

One day I was playing too loudly in the fort I built in the living room, which woke my stepfather up from his Sunday afternoon nap. Without a word, he marched into the living room, grabbed me off the fort and brought me to the back bedroom. I let my body go limp, as I always did before a beating, a sign of resignation.

However, my uncle was visiting that afternoon and had not realized that this was the norm. And not even a minute into my spanking, my stepfather’s slapping hands were suddenly off me and I could hear him and my Uncle fighting in the living room, followed by the crunching sound of fist colliding with face.

“You ever touch my niece again and I will kill you,” Uncle Billy told him.

An hour or so later, my stepfather sheepishly sauntered into the bedroom with a black eye and a bloody tissue crammed up one nostril. He apologized to me, and he never hit me again.

About a year later, after my stepfather had separated from my mother and left town, I watched one night as my Uncle and mother, clad all in black and donning ski masks, climbed onto the fire escape outside my bedroom window. When I asked them what was going on, my Uncle put his finger to his lips.

“Shush, snooks,” he said soothingly. “Just go back to sleep. This is just a dream.”

The next morning our living room was filled with stereos, televisions, VCRs, jewelry and piles of cash. These things would all then disappear piece by piece over the next few days and then policemen would come to our door with a warrant. They would tower over me and ask me questions about my Uncle and mother and if I ever saw any strange behavior or noticed things that didn’t belong to us in our apartment.

My mother told me to be truthful, while she grabbed my upper arms hard, sinking her fingernails so deeply into my skin they drew blood. She nodded to me while her eyes told me to lie. So I did. But not for her. For my Uncle Billy, who already had a record and could go away for good this time.

But Uncle Billy ended up taking the fall for the whole operation — sentenced to years hard time. He knew if my mother went to jail my brother and I would be seized by the state and sent to foster care, where worse things could happen to us.

By the time my Uncle was let out, I was 13 and about to enter high school. My once honey-colored hair had turned several shades darker, and I now had breasts and bled monthly. My uncle no longer knew how to relate to the young woman before him, and I had in turn started to resent him — for how his crimes and addictions hurt my grandmother, but also, for leaving me when I needed him most.

We were awkward and tentative with each other over the next two years. And then he was dead. When I heard the news, I kept wanting to cry but couldn’t, because I had really lost him the last time he went to jail. He had come back broken, distant.

But even then, he never stopped believing in me.

One time, shortly before he died, he had a friend over.

“Oh, so you’re Laura,” the guy had said after we were introduced. I nodded.

“Your Uncle says you’re special,” he continued. “You’re the one who’s going to make it out and go to college.”

My Uncle Billy — his faith in me, and his willingness to be sent to prison, lest I be sent to foster care — was a big part of why I did, in fact, manage to make it out.

Laura Kiesel is a freelance writer living in the Boston area. Her articles and essays have appeared in Salon, Orion, Narrative.ly, Earth Island Journal and others. She is currently completing a collection of connected personal essays, titled “The Drug Addict’s Daughter.”