The moment I hear someone died, jealousy swells up inside me. I’m not jealous of the dead. It’s fleeting envy of the bereaved for this opportunity to mourn.

Like most of my psychological dents, this one is about my dad. He was a New York City electrician who looked like a cross between Steve Perry and Al Pacino. He took me on car trips to the Lemon Ice King of Corona, carried me on his shoulders to the Whitestone Shopping Center to rent “Three Men and a Baby” on VHS weekend after weekend, and bought me every pet in the pet store and some from the back of a stranger’s van.

The van pets weren’t long for this world, and neither was he. My dad died in 1990 when I was 6. Since we were a working-class Italian-American family with repression, overeating, and pretending as our go-to coping mechanisms, we did not grieve together or talk about him anymore. Life went on, on the surface undeterred. My mom overcompensated by filling our living room with Christmas presents we couldn’t afford.

After Dad died, I did my best never to cry, or appear sad or scared. I earned stellar grades, participated in a host of extracurricular activities, and I never complained. Because I didn’t want to be the final destabilizing card in our wobbly house. Perhaps my mother would die too.

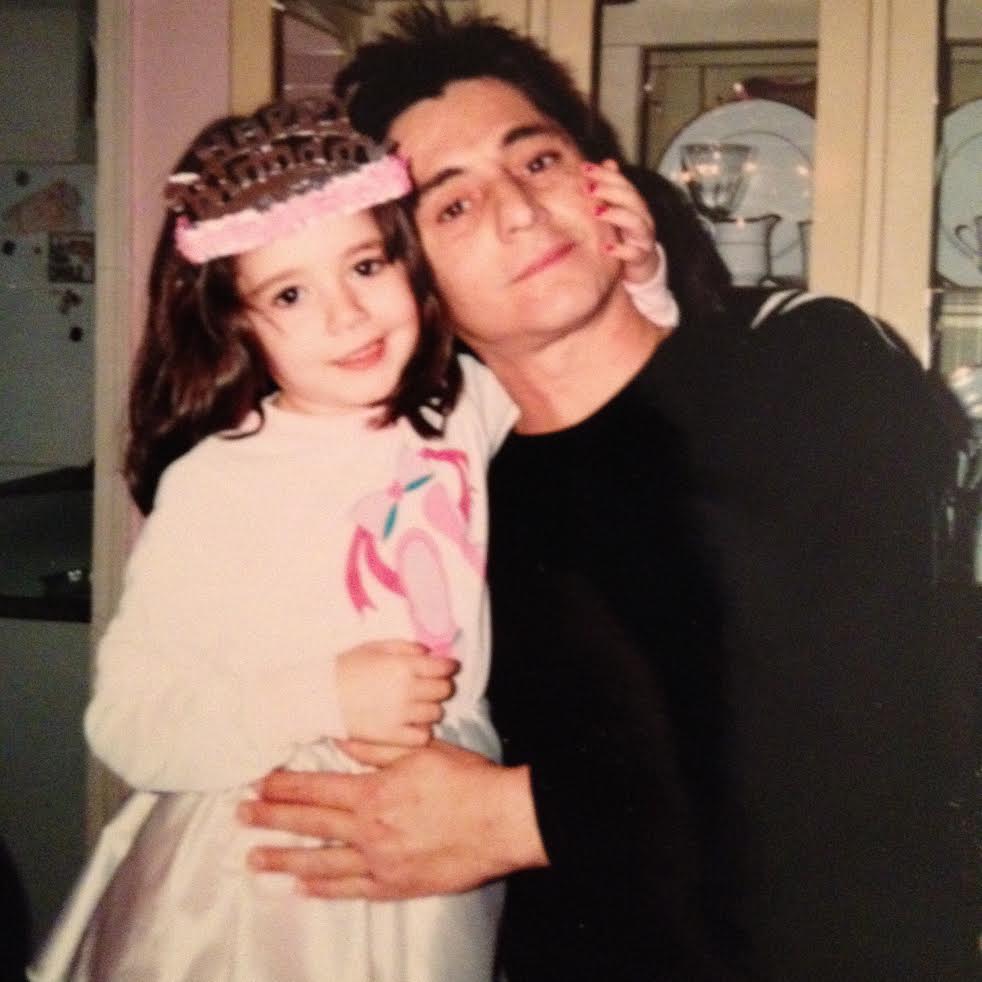

The author and her later father (Courtesy of Nicole Ferraro)

I didn’t probe this dynamic until I was in my mid-20s when it hit me that I’d been harboring repressed grief over my father’s death all these years. When I ask my family about whether they ever thought to talk to me about my dad, they say, “You seemed happy. We didn’t want to upset you by bringing it up.”

Of course, that which is ever-present can’t get brought up. It’s just there, an unacknowledged sickness lingering, thickening the air until we can’t see each other. And now it feels too late to mourn with any profound meaning. This long-ago loss of this father I remember loving like crazy, but don’t remember as a real person, feels abstract.

One of my sticky-note life memories is of being in the back of the funeral home during my dad’s wake. I was dressed in my red-and-black checkered dress from kindergarten picture day, white socks, and shiny Mary Janes, and my grandfather came over and to try to take me up to my father’s casket. I pulled back, and my mother rushed over to steer him elsewhere. That was that. No one else asked me to go up, and I don’t remember talking to anyone about why I didn’t want to. Of course, I was afraid. I didn’t want to see a dead body, no less my father’s.

READ: Why I Like Funerals More Than Weddings

But six months later when my 33-year-old uncle died of a brain aneurism, I went up to his casket. I don’t know what changed. I crossed over from 6 to 7, a more mature number, and perhaps that was enough. I can still see his face, smooth like clay, with an escaped eyelash stuck to his cheek. My aunt tweezed it off with the tips of her red-polished nails, and she and my cousin collapsed into each other, their backs shaking as they sobbed. I sat there, witnessing their shared grief, witnessing my first dead body — too late to see my dad’s. That realization rushed through me like wet cement. I’ve felt aloof from my life ever since.

I confess that it isn’t totally true to say that my initial reaction to death is jealousy. Just before that, I feel a brief a surge of excitement — like a craving, an opening that’s about to be filled. It turns into jealousy when I register that it’s not my opening.

I don’t crave the losses still to come. I dread and fear them. I just long to give meaning to the one that shaped everything else. Every new loss triggers the one that got away.

This past winter, I wrote and performed a solo show about losing my father. It was gratifying and liberating to weave the experience into a story and share it in a physical space with other people after years of pretending and non-expression. It encouraged people to open up to me about their stories in return, and respond to mine. It was the first time I shared in an honest way, in front of family, friends, strangers. I felt seen. I grew a little from it.

Just a little, though. Despite knowing better, I harbored this made-for-TV idea that this performance was going to feel like a major act of public grieving, that I would complete it, feel reborn, and get something akin to closure. Done with Dad’s death. Next? Write a feminist comedy!

But when I next sat down to write, I returned to the same place, the same scene that confounds me still, that I will investigate like some obsessed detective until it becomes real, until I can see his face in that casket and have that loss feel valid, and not like a discoloration in the rug we danced around until we were too dizzy to remember why.