Not long ago, I found myself shuffling through a small East Village antique shop, tucked away between a tattoo parlor and a hair salon, looking for a subject to write about for my journalism class. The assignment was to find any type of memorial, be it a monument commemorating unknown soldiers or the Facebook page of a lost friend, and to write about its impact.

As I browsed through the shop’s nest of eccentricities—collections of old surgical instruments, decorative Gurkha machetes—I came across a drawer labeled “Memorials.” I opened it to find a mix of vintage postmortem photographs, antique personalized coffin plaques, and death notices of days gone by. “Coffin plate, mom $65,” read the back of one. “Death notice $20,” read another. The remainder were photos of peaceful-seeming children, laid to rest in open coffins surrounded by flowers.

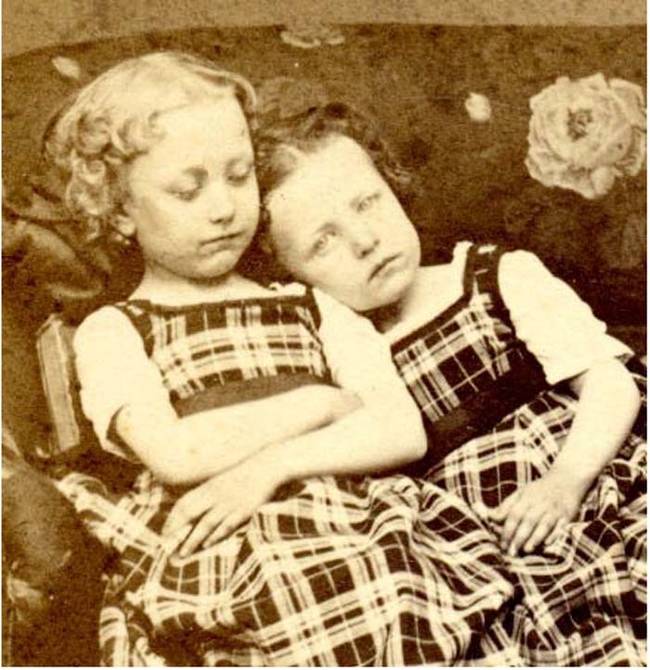

The experience was distinctly unsettling. Who were these people? How did their photos end up here? I wondered. I imagined it was some strange, Victorian convention that had thankfully long since passed. But to be sure, I began researching, and I found the truth was quite the opposite.

READ: Grief Landscapes: A Photo Essay

Ann Vetter of Cleveland, Ohio, lost her daughter Grace, who was delivered stillborn, in February 2015. Twenty-four hours before the delivery, Ann learned that the baby’s heart had stopped, and one of the first things she told the nurses was, “I want Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep to come.” She was referring to the non-profit that works with volunteer photographers to provide professional-level photography, free of charge, to families who have lost a newborn.

An example of Victorian death photography. (via Tumblr)

The organization is one of very few of its kind. It was created in 2005 when its founder, Cheryl Haggard, lost her six-day-old son, Maddux, to myotubular myopathy, a deadly condition that inhibits muscles used for breathing and other vital movements. Cheryl and her husband hired a professional photographer to capture their last moments with their son, before and after he was removed from life support. Cheryl decided to start an organization that could provide similar services for other grieving parents and now, NILMDTS, as her group is known, provides its services throughout the United States and in 40 other countries.

Initially, many families are put off by the morbidity of photographing their dead children. “Often something tragic happens during birth,” she said. “The families are shocked and they push back, but of course they want to remember this child. So I tell them to take the pictures anyway. They don’t have to look at them if they don’t want to.” The purpose of these photos is not to look at an infant that has passed away, she said, “but to look at love, and the bond between parent and child.”

For Ann, who used Cheryl’s organization to document Grace when she was delivered, the photos have been incredibly fulfilling. She told me the story of a high school friend who had lost a newborn, but who was unable to take pictures of her daughter because her disposable camera malfunctioned. After hearing this story, Ann said she burst into tears. “What would I do if I didn’t have my pictures?”

Although Ann’s husband felt uneasy about the pictures at first, it comforted him to see how they helped Ann through a difficult time, and they eventually became a comfort to him, too. The photos also help their four-year-old son understand that he once had a sister—a notion that might have been completely lost on him without the photos. Now he calls all little babies Gracie. For some families, these photos, far from conjuring that unsettled feeling I had experienced when I first stumbled on them in the antique shop, have been a key component in helping them heal.

“Society’s attitudes towards memorial photography are evolving,” said Ann. “Before Grace was born I remember seeing those Victorian postmortem pictures and they just seemed morbid. Now I definitely see it from a different angle.”

This may be why there is a market for the items I found in that antiques shop drawer. The shop’s owner, Evan Michelson, said that most of the buyers are young women. “Maybe they’re people who are working out issues,” she said. “Some people like daring things, or something to provide shock value. Others are just looking for thought-provoking pieces on life and mortality.”

Elettra Pauletto lives in New York City, where she is pursuing an MFA in creative writing and translation at Columbia University. Her work has appeared in Guernica, River Teeth, The Montreal Review, and elsewhere. You can follow her on twitter @ElettraJP.

Watch to learn more about the work of Now I Lay Me Down To Sleep: