The last night I spent with my father, we shared a twin bed in a dumpy motel somewhere off I-95 near the border between Virginia and North Carolina. My stepbrother took the other bed. My dad had driven more than 12 hours from Boston, towing a trailer of motorcycles. We just needed some rest before the last four hours to Myrtle Beach, the final stop on our first family road trip ever.

That twin bed was the closest, physically, I’d been to my father since I was in high school. I could hear his breath, feel his warmth. Before nodding off, I told him of my plans to marry my girlfriend. I was 26. I was hoping that this was the start of a redefined father/son relationship, one where we could talk about adult things.

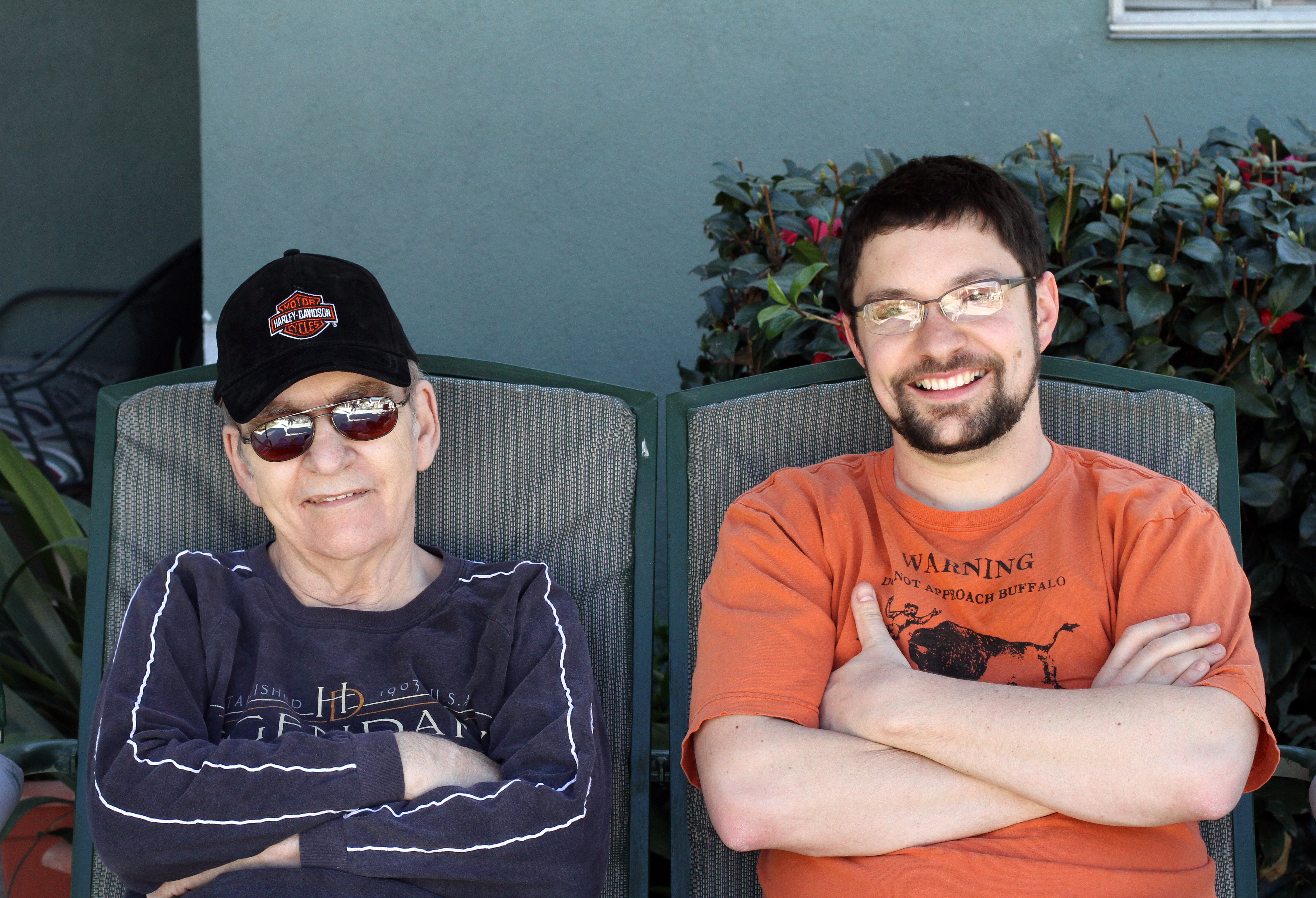

Ryan and his dad

And that trip did completely redefine our relationship — just not at all how I had hoped

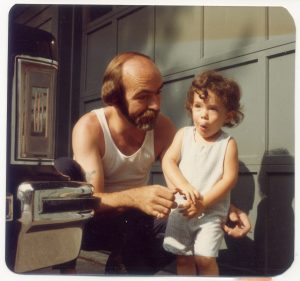

My father had always been a risk taker — a man of action, not deliberation. He drove motorcycles and fast cars. He seemed to think he was invincible, and he liked to test that theory. But when I was born, and he was 39, he sold his Harley. He often reminded me of that fact, as if to say, “You’re the only reason I’m still alive.”

Then one day during my senior year of college, I answered the phone to hear only the sound of a Harley revving in my ear. Now that I was an adult, I suppose he felt he could be wild again.

Technically, that night in the hotel in 2007 wasn’t the last night I spent with him. But after the following day’s motorcycle accident — traumatic brain injury, four weeks in intensive care and months of rehab — my father wasn’t really my father anymore. Our roles were reversed and I became a reluctant father figure, alongside my stepmom’s leading role.

For the next five hellish years, my dad and I relived being a father and son in this upside down world. He went through the stages of early childhood in a matter of a few months. In the rehab hospital, I held him as he relearned how to walk and go the bathroom. We practiced simple conversation; his words were a jumble at first, but soon resembled actual dialogue. We studied a photo book my stepmom had made – “This is your house, dad. Do you remember your address?” “This is your sister. What’s her name?” “No, your motorcycle is gone.” Soon, he was out of rehab and back home with my stepmom. Things seemed to be improving. Then came his “teenage years.”

My dad regained his will and soon insisted he was 100% better. He wanted his car keys back. This terrified me. I filled up with anxiety about my dad’s safety, his fragile state of mind, the safety of others. I felt uncomfortable in my new role as the sensible one. Regardless, we went on drives together. Behind the wheel, he seemed calm and focused, while I sat in the passenger seat white-knuckled, shouting out every possible hazard along the way.

Related

I recognize this constant risk assessment now that I am a father to a young daughter. I see risks all around me – that tall bookshelf over there, that steep staircase back there, that piece of sharp plastic jutting out right here.

But my own father wasn’t as fazed by risks, big or small. In fact, risk was essential to him. “When I get to the age where I can’t lift my leg to get on this bike,” he said of his Harley, while I photographed the bike in his garage back in 2003, “I don’t want to live anymore.”

I was shocked by his brazenness. “Dad! Don’t say that!”

Now, after the accident, he may have been able drive a car, but there was no way he could ride a motorcycle. He was weaker, slower, often just slightly out of touch with reality in some peculiar way. He’d wear his slippers out in public or hear a noise and imagine that someone had broken into his house. He was also an emotional wreck, oscillating between anger, joy and sadness. He could seem like the old dad I knew — warm, jovial, sarcastic — and then he’d say something peculiar and I’d remember our transposed roles.

I was haunted by the knowledge that if he’d had the self-awareness to understand his situation, he would rather be dead.

In fact, there were a few times that I talked him down from committing suicide. He’d want to drive off a bridge or hang himself with an orange extension cord in the garage. Part of me wanted to let him do it. He wasn’t getting any better. My former dad, my real dad, wasn’t coming back. I felt worn down, and my stepmom, who bore the brunt of his care, did too.

A few years after the accident, I remembered that conversation in the garage, and realized he had been serious. A terrible, gripping thought popped into my head. I had to find a way to kill him. There was no plug to be pulled, though. No quick way to make everyone’s pain stop. I had heard assisted suicide was legal in Oregon. I thought I could take him there by car, just father and son, and I could give him an opportunity to die with dignity. We could finish that road trip we had barely started.

I hoped, too, to spare my family the burden of having to watch him die ungracefully. But as I began to plan how to do it, I was overcome with grief. I couldn’t let myself actually plan to murder him — what kind of person would that make me?

I tried to move forward with my own life, to ignore the impossible choice I couldn’t make. Then the phone would ring and I’d bristle:

“So he was missing for 12 hours and now he’s in the custody of the U.S. Marines?”

The absurd had become the norm. There were still occasional happy memories, though. His brief speech at my wedding. The way his voice would tremble when he’d tell me he was proud of me. But at some point, my desire to keep my memory of my old father intact outgrew my desire to maintain this new one-way relationship. I retreated to happier memories and grew cold and pragmatic when dealing with my new dad.

I wish he had died that day, in the motorcycle crash. It took a long time to admit to that feeling and I still feel guilty saying it. But at least it would have been a simple death, heartbreaking and painful and sudden. Instead, he had two deaths — one quick, one slow.

His physical death, in 2012, was no less traumatic for me. My dad spent most of the last year of his life in a state of bewilderment, whether due to heavy doses of anti-psychotics, psychological isolation, or the brain injury itself. When he came down with pneumonia, we decided not to treat it. We thought it would painless and natural.

But it was slow and confusing and left my father agitated on his deathbed.

I dreamt of that trip to Oregon, and I regretted not taking him there and facilitating a dignified death. In the end, I squeezed his hand, rubbed his arm where my name was tattooed.

“It’s ok, dad, we’re all going to be fine,” I told him. “Please don’t worry, you’re safe, relax.”

I said goodbye to that man and began the more formidable task of remembering the loving father I lost five years before.

Ryan Murdock is a filmmaker based in New York City. His feature documentary “Bronx Obama” tells the story of a Barack Obama impersonator facing an identity crisis. His work has appeared on Showtime, the SundanceNOW Doc Club, This American Life, the BBC, The New York Times, NOVA, StoryCorps and others. He is also a father. Follow Ryan on Twitter @ryan_murdock.