Art by Natalie Cosgrove

“It just so happens that your friend here is only MOSTLY dead. There’s a big difference between mostly dead and all dead. Mostly dead is slightly alive.”

– Miracle Max from “The Princess Bride”

And this is the tough part. I go to the hospital to say goodbye to my 88-year-old grandfather, who will die the next day. It was impossible to say goodbye when I knew he could understand me, with the possibility I would see him again and maybe even another time after that. But this is different, and the words that would have rivered through my mouth a few weeks ago have crystallized. Here mostly dead feels utterly and completely dead. The only thing that feels alive are the memories that come like tidal waves so that I must ground myself when I feel one coming on. When I walk into the hospital room, his mouth hangs dry as city dust.

And yet, with orchids, mostly dead is very much alive. So I pour my energies into them. They are mysteries, beautiful and strange. Sepal, labellum, tubers: even the parts of an orchid plant have magnificent names. Their petals are arranged so that at times they look like wild animals – their flower mouths growling, yawning, or forming an O of — splayed open in dialogue with the world.

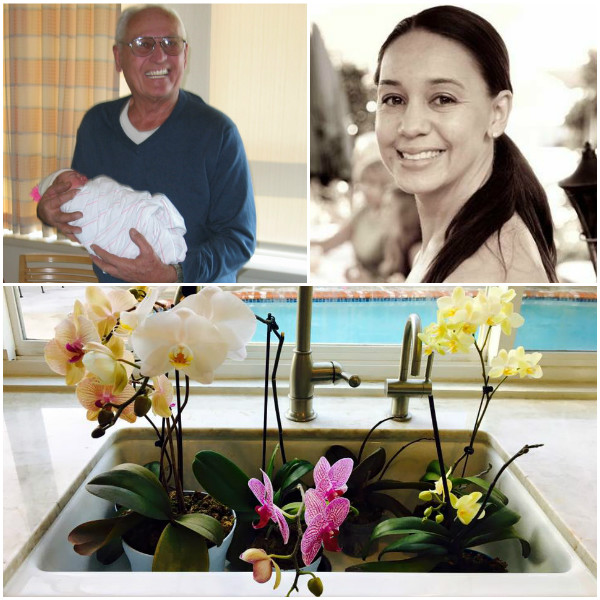

Clockwise from top left, the author’s grandfather with her newborn daughter in 2007, the author, and her sink full of orchids (better than dishes).

My grandfather built pools for a living. He was very much out in the world, working with his calloused hands, piecing together the tiles, pouring the concrete, building one California dream after the next. He loved his own pool and the manicured garden around it. Perhaps I’ve inherited some of his green thumb or his ability to make things.

Orchids are like goldfish. At some point in your life, you will end up with one, whether you want it or not. Then, you are tasked with the responsibility of trying to keep it alive for as long as you can. This is not an easy feat. Life is chaotic, and watering requires a strange discipline. Without water, the thirsty orchid will send its roots skyward, searching for relief from its desiccated soil. Preoccupied with other things, you will not think about the orchid again until the paper-thin petals fall away, and the stem and leaves slowly give up their vibrant green and die. You will remorsefully pick up the sad plant and plop it in the trash. There are plenty more orchids in the sea, so your guilt will not last that long.

But I know differently. Sometimes you can bring the dead back to life.

I know that you have essentially buried the poor plant alive.

READ: In Mourning, with Broadway and Carne Guisada

My grandfather poured concrete like a parent pours milk into cereal bowls. He was loud, tan, and muscled round and strong from hard work, hot dogs grilled in his sunny backyard, and the daily Bud Light or Corona that he would savor. When he came to see our newly purchased home for the first time, he had been retired from pool building for many years. He loved the home, walking out into the backyard, surprised to find it was an Anthony pool, one he may have even built 40 years before.

When we moved into this home three years ago, it seemed that everyone who came to visit brought an orchid. Orchids are tenacious. Their blooms last for a long time, even when you don’t take care of them, so I became accustomed to a windowsill full of long, beautiful plants. Their green greeted me each morning; their blooms drooped over the dishes in the sink each evening. It was a kitchen jungle: my own little flower paradise amid the chaos of housework, cooking, and bills. When my orchids started to die, I went about my business, knowing that eventually they would end up in the trash, like all of the goldfish and orchids that came before them.

My grandfather didn’t believe in throwing things in the trash. He was one of seven siblings. He encouraged us to eat the crust right along with the bread, to suck every morsel off the chicken bone, to cultivate rather than cut down. He encouraged us to find the life in life.

Once the first orchid was dead, I scooped it up with one hand, opened the trash with the other, and stared down into the decaying abyss that was to be its new home; but the orchids and I had developed a relationship, and I couldn’t bring myself to drop the plant in. Instead, I googled, “How to take care of orchids.” Sitting down on a white kitchen stool by their withering bodies, I watched a 30-minute instructional video. The lady’s soothing voice pointed out that the orchid owner should replant orchids once every one to two years, twisting their escaping roots back into the bottom of slightly bigger pots. She explained that orchids should be fertilized, cut down, and mended with a sprinkle of cinnamon on their open wounds.

After my grandfather retired, my mother took his work boots and gilded them with gold paint, filling them with cement: two relics of a satisfying career. The boots keep doors open in her house. They are welcoming and heavy.

A few weeks later, my sister lets herself into my home, walking into the kitchen. She has the same problems as most people do with orchids and goldfish. In her hands is a beautiful, square glass container. It is clear and textured with small half domes dotting its entire exterior. In the container is a long, miserable orchid stem. She challenges me to bring it back to life, setting the plant down on my kitchen counter I feel as if I have some special orchid magic … that I should be wearing scrubs … and silently start working on my new patient. There is a small, plastic pot with the orchid inside of it embedded within the container, so I take it out, replanting the stem with the correct ratios of peat moss and bark. I am a forgetful waterer, so I add more peat moss, since it retains moisture for long periods of time, and requires less frequent watering. I add some bark to help the excess water drain out so the orchid’s roots don’t rot away. I am careful with my restoration work. After repotting the orchid, I cut it down, cinnamon the slice of orchid stem that is left exposed, and satisfied with the job, go about my business. When she comes three weeks later she is astonished to find a flourish of blooms bursting forth from the “dead” plant. It is a miracle!

I’ve always loved miracles. When my grandfather couldn’t build pools anymore, he started to build birdhouses. Houses to protect and shelter the miracle of life that could take flight. My grandfather was a miracle. This is the echo that is left behind when he died: the potential of a full, wonderful life.

A flowerless orchid is still beautiful because of its potential. Often, things can be saved with a little added effort, and often, they are worth saving. I know that there are many things in life I will eventually have to let go of… but my orchids are not one of them. I bend over my sink, thinking of how much my grandfather would love these blooms, I bless them with water and well wishes, cultivating what is very much alive.

Alexandra Umlas lives in Huntington Beach, California. with her husband and two daughters. She is currently an MFA student in the poetry program at California State University, Long Beach.