On the second anniversary of 9/11, my mother, who had been undergoing treatment for breast cancer following a mastectomy, blacked out alone in my parents’ apartment. She came to on the floor, uninjured but dying. Chemo and radiation had eradicated the disease in the rest of her body but the cancer had metastasized to her brain. Twelve days later, on a Tuesday, she died. Four years later, my father was diagnosed with colon cancer just a few months shy of his recommended five-year colonoscopy; believing he had appendicitis he’d driven himself to the emergency room. He died three months later, having never left the hospital. Never getting the only thing he wanted, which was to go home.

On the second anniversary of 9/11, my mother, who had been undergoing treatment for breast cancer following a mastectomy, blacked out alone in my parents’ apartment. She came to on the floor, uninjured but dying. Chemo and radiation had eradicated the disease in the rest of her body but the cancer had metastasized to her brain. Twelve days later, on a Tuesday, she died. Four years later, my father was diagnosed with colon cancer just a few months shy of his recommended five-year colonoscopy; believing he had appendicitis he’d driven himself to the emergency room. He died three months later, having never left the hospital. Never getting the only thing he wanted, which was to go home.

My parents’ deaths were very different. My mother’s decline was so rapid, so devastating, that afterward I insisted to my husband that we get life insurance. It seemed advisable, considering Patrick and I were new parents to an eight-month-old boy, and although it provided neither consolation nor assurance against loss, in my grief literally buying insurance felt like the only sound decision I was capable of. Though my father had been told his diagnosis was surmountable, in those last weeks he worked closely with his attorney to finalize all of the details of his will. It was a tremendous asset in making all the arrangements my husband and I had to handle after his death, making a terrible situation at least easier logistically. I knew that Patrick and I needed to have wills too — by then we had two children — but it was so easy, so welcome to put it off. So we did.

It took three years after my father’s death for us to commit to drawing up the wills we knew we needed.

The attorney we used, Anne, had been recommended by a friend. And though it seemed to me that she had the Grim Reaper for an office mate, she seemed to like her job and we developed an easy rapport.

We didn’t deal with death right away. First we tackled durable powers of attorney and the business of advance directives and appointments of health care representatives for both of us; the matter-of-fact housekeeping details of life support, tube feeding and choices to make regarding advanced progressive illness and extraordinary suffering, pain control, life support and hospice in the event either one of us was still here but very much on our way out. But then we started to get into the things I didn’t know to brace myself for, things I’d never even heard of or thought about, like who we’d name our contingent beneficiary.

What’s a contingent beneficiary? I asked.

That’s the person you leave all of your assets to if you, Patrick and your two sons all die. Anne said.

Related

Then we had to appoint who we’d ask to raise the boys if only the two of us died — and then pick a backup for the first parties in case they perished. This, at least, Patrick and I had discussed at length. Our first choice was for the boys to live with the doula who had helped deliver them, who was a dear friend, and her partner. They had known the boys for years, and while they had decided not to have children of their own, they didn’t hesitate to say yes to our request when we asked. The second couple we asked did have kids of their own, and after they too said they would take the boys should something happen, they admitted they had been putting off sitting down to make the same decisions for their own family.

The longer our meeting with Anne went on, the more I wanted someone else to come and be me so I didn’t have to. We don’t really need this, I kept thinking. Doing a will is for other people. People who die. Of course our attorney was only doing her job, page by page, detail by painful detail. But as soon as she’d referenced the untimely hypothetical deaths of my sons I wanted to end our meeting and walk out.

How dare you? We’re leaving right now. You should be disbarred. Creating a scene and taking umbrage at what she’d said was a compelling temptation. I was willing to do anything, including behaving badly, to provide a distraction to the thought of my sons being deceased.

Of course she wasn’t intending to hurt or upset me at all. But because, being a professional, she could speak so easily, albeit compassionately, of an unspeakable scenario, it was painful. I was desperate to eradicate the suggestion at the heart of the statement she’d just made, to regain some control of that imagined narrative.

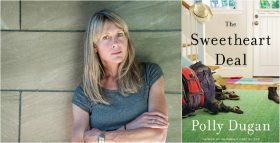

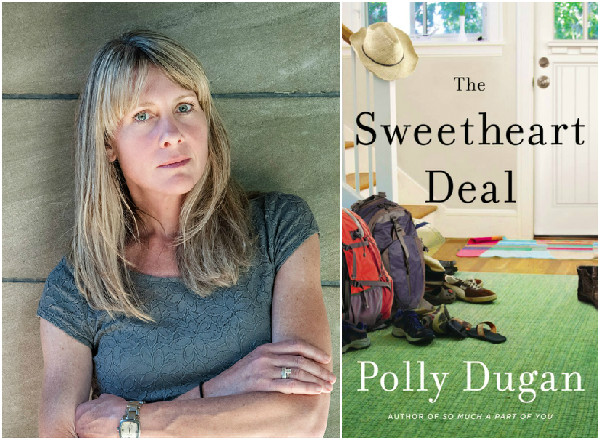

As a writer, one of the most edifying pieces of advice I’ve ever gotten was this: Write about anything you can’t get rid of by other means. And so I have. Fiction has turned out to be the one place where I haven’t hesitated to confront death. In my stories I’ve killed off a twelve-year-old boy, premature babies, beloved mothers, a volatile father, treasured pets, firefighters. My novel, “The Sweetheart Deal,” is about a woman who must face life as a single mother to three boys after her husband dies in a tragic accident.

The characters I hope my readers will connect and identify with are the ones left behind — those still living and surviving and grieving, whom I’ve forced to sustain uncomfortable and painful circumstances. When I write their stories, when I take control of their narrative, I find myself becoming less afraid, cautiously optimistic and hopeful.

The truth is, we’re all probably far less alone than we realize in our anxiety about death. The success of HBO’s “Six Feet Under” was proof of our collective curiosity. In recent years, organizations like Death Salon and The Order of the Good Death and, yes, Modern Loss, have been founded by groups comprised of historians, writers, artists, musicians, funeral industry professionals, and armchair researchers. Together they shine a light on the culture of death to prepare a death phobic culture for their inevitable mortality. And although I can’t foresee the subject being brought up at parties or meetings or in carpools with any kind of ease the way other timely topics are, no matter what great strides these organizations make, there are places where death is discussed without apology or caveat or reservation.

During the course of my research for “The Sweetheart Deal,” I visited The Dougy Center, which I knew provided a safe place for local children, teens, and their families who are grieving to share their experiences. What I didn’t know is that the scope of Dougy’s work extends far beyond my hometown of Portland, Oregon. Their experts have worked on the ground with communities impacted by large-scale tragedies including the families in Newtown, Connecticut following the Sandy Hook shooting. Their expertise has served as a model for the founding and structure of 500 grief support organizations worldwide.

I didn’t write “The Sweetheart Deal” specifically to explore my own anxieties about loss and grief, but doing so served as a kind of exposure therapy, and there’s more to come; that first appointment was just the beginning. At the end of our meeting with Anne, after we’d tackled all of the unthinkable issues, answered all of the uncomfortable questions, she advised us that we should reconvene in five years, so we could make any updates.

That’s where we are now, the five-year mark. While we remain healthy and well, the details only seem to grow more complicated. In 2010, the idea of having a “social media will,” a plan for what will happen to your online presence after you’re gone, wasn’t part of our conversation. But it’s something to address now. I’m expecting we’ll discuss it when we meet with Anne, who I’ve already emailed about an appointment. I know that she will again coach us through unfamiliar terrain and I now know to expect the unexpected. And I know, despite our discomfort, we’ll make responsible decisions we feel as good about as we possibly can, knowing they’ll only be important once we’re no longer here. In the meantime I’ll keep writing about what I can’t get rid of any other way.

Polly Dugan is the award-winning author of the recently released “The Sweetheart Deal,” a Portland Monthly Essential Book and one of Library Journal’s “Hot Summer Book Club Reads,” as well as the story collection So Much a Part of You. An alumna of the Tin House Writer’s Workshop and a reader at Tin House magazine, Polly’s fiction has been featured as a Narrative Story of the Week and awarded an Honorable Mention in Glimmer Train’s Short Story Award for New Writers contest. She lives in Portland.