Neurologist Oliver Sacks, who died of cancer last week at age 82, assessed the minds of his patients through direct observation and social interaction. A physician, a writer, a former weightlifting champion, he was, above all, a great listener. His own mind was curious, quick and expansive. He overpaid his attention.

In 2009, while producing “Musical Minds,” an adaptation of Oliver’s book “Musicophilia” for the PBS science documentary series NOVA, I wondered: What would we see inside the brain of the most famous neurologist in the world? Had his thousands of case histories made a visual imprint? Could we perhaps retrieve his unfinished manuscripts, discarded stories, and flashes of insight?

Related

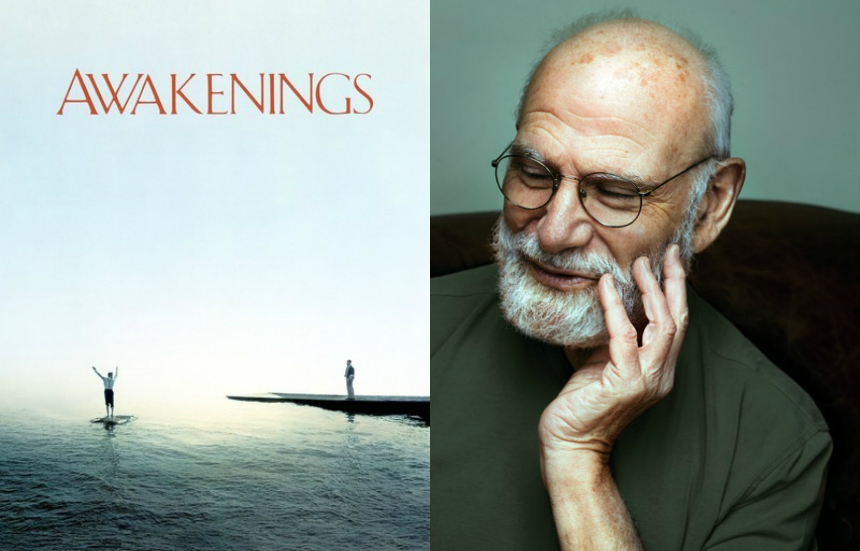

Oliver, the author of the memoir “Awakenings” (later made into a film starring Robin Williams and Robert DeNiro), was so adept at translating the neurological experiences of others into words. Could his own brain show us why he was so unique? I asked Oliver if we could put him into a functional magnetic resonance imaging machine (fMRI) to watch his brain react to music (one of his dearest loves). He begrudgingly agreed.

With the help of Joy Hirsch and Hal Hinkle from Columbia University, our team devised two experiments. First, we would compare brain scans of Oliver listening to music with brain scans of Oliver imagining listening to the same piece. Oliver chose “Diversions” by Joseph Horovitz, a piece that he knew well and could play on the piano from memory. He listened, we scanned. He imagined the song, we scanned again.

Comparing the scans, we saw strikingly similar activation in his brain, the major difference being activity in Oliver’s frontal lobe during the imagined experience. Oliver’s brain had “played” the song back nearly verbatim, as if hitting replay on an iPod located in his frontal lobe. I wondered if future neuroscientists might someday be able to identify the song simply by looking at the scans — read the rhythm, tone and pitch in Oliver’s auditory cortex as if it were a form of sheet music. The team demurred; Oliver’s brain — any brain — is not simply a recording device.

In the second experiment, we studied Oliver’s response to Bach (which he loved) and his response to a comparable piece by Beethoven (which he avowedly disliked). The songs were as similar as we could find — tempo, instrumentation, volume, all shared. As he listened, Oliver talked to us through a microphone from inside the giant magnet, so we could document and more intimately understand his experience. He found the machine claustrophobic and cold, but thankfully he found at least one piece of music to be moving. Oliver’s brain lit up like a firecracker at Bach, displaying a colorfully coordinated dance of neurons. But his brain was strikingly quiet toward Beethoven.

Oliver seemed to almost feel bad about this: He quipped, “Sorry, Ludwig,” while looking at the scans. Beethoven had composed a workable song using the tools of music, yet Bach stirred great emotion in Oliver with those same tools. Emotional connection between artist and audience is what makes a work of art great, whether it a piece of classical music or a nonfiction story of a man and a hat.

Perhaps we didn’t need an fMRI to know all this. If anything, the results of both experiments confirmed what we already knew from direct observation and social interaction: Oliver possessed a stellar memory and an unwavering unity of heart and mind. His humane way of practicing medicine, and his prowess at paying attention to the world, has been shared with millions through his writing and (reluctant) TV appearances.

His work is a testament to the interdependence of science and creativity, and has become a blueprint for me in my career as a documentary filmmaker. The staggering output of his active mind will undoubtedly interest many generations to come, and his voice will echo in the auditory cortices of future scientists and artists alike.

Ryan Murdock is a filmmaker based in New York City. His feature documentary “Bronx Obama” tells the story of a Barack Obama impersonator facing an identity crisis. His work has appeared on Showtime, the SundanceNOW Doc Club, This American Life, the BBC, The New York Times, NOVA, StoryCorps and others. He is also a father. He wrote previously for Modern Loss about his father’s traumatic brain injury and death. Follow Ryan on Twitter @ryan_murdock.