EDITOR’S NOTE: October is Pregnancy & Infant Loss Awareness Month.

By the time I wake up, my husband Harlan has already written his letter. I can see it on his computer screen, but decide not to read it yet, not wanting to be influenced. I decide to write mine longhand and open a spiral notebook and start with the words, “Dear Nina.”

It’s April 25, the day when we lost Nina, our baby daughter, five weeks before she was due to be born, four years ago exactly.

Once we’ve completed our letters — my 6-year-old son Aidan writes one, too, this time—we buy balloons at the supermarket and head north to a quiet, pretty beach to let them go.

On the sand, we read our letters, one at a time. Harlan cries as he wonders aloud if Nina’s morning ritual would have included rubbing our cat’s tummy or eating cinnamon toast or watching squirrels in the yard. “I feel like I know what you would have been like, your personality, and that just makes me miss you more,” he says. When I’ve finished reading mine, Harlan says, “That was beautiful, baby,” and reaches over to squeeze my shoulder. Aidan proudly reads his birthday card: “Happy Birthday. I love you. From Aidan to Nina.” Only the words Aidan and Nina are spelled right.

Related

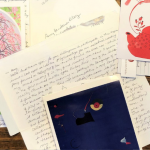

We attach his card to the balloons and return the other two letters to their envelope, where they will join the stack of those we’ve written in previous years, along with the condolence cards, the soft pajamas, the beads my friends had threaded onto string at my baby shower, the tiny cap and pink knit sweater, all bound snugly in a small satin box. Harlan hands the balloons carefully to Aidan, who struggles to hold onto them in the wind, and together we walk toward the water’s edge. Aidan smiles as he lets them go. We stand together, squinting upward as the light pink, dark pink, purple and green balloons— one for each year she’s been gone — float up into the air, getting smaller and smaller, until they’ve disappeared from view. Before we leave, Aidan builds a mound of sand. Harlan and I gather shells, sticks, stones, driftwood, even a crab’s claw, transforming the mountain of sand into a tribute to Nina that will remain after we’ve gone.

We didn’t consciously create a ritual to commemorate Nina. The first time we did it I was still bloated and achy from the pregnancy, delivery and my milk coming in. Harlan had wrapped the movie he was shooting (he’s a cinematographer) and was now home, watching me with worried eyes as I napped, cried and did my best to tend to our son. Harlan had been forced to get out into the world and function normally, but I still didn’t know how. All I knew was I couldn’t be in Cambridge, where we live, on my due date.

Some friends arranged for us to rent a cottage on the coast of Maine. On our due date, we wrote letters to Nina and, on our small private beach, read them aloud, along with a poem I’d found that felt relevant, and gathered a bouquet of wildflowers, which we placed on a boulder that would be surrounded by water when the tide came in. We knew that eventually they would be washed away and somehow that felt right.

The following year, this time on April 25, the anniversary of the day I had delivered Nina, we spent the weekend in another small town in Maine. Again, we wrote letters. This time we sang “Happy birthday,” as we set a cluster of balloons flying up into the grey sky.

Twice Nina’s birthday fell on a weekday when Harlan was unable to miss work, so we performed our ritual in beautiful spots in Cambridge, once in a park and once on the bank of the Charles River. But if we can, we leave our home and go to a peaceful place that reminds us of that first beach, where we went when the pain was still new, the wound still raw.

This year I am surprised by the depth of pain Nina’s absence still brings me. I thought it would eventually become more remote, but it seems to have deepened, in fact, perhaps because we decided not to try to have another child. In spite of all our very good reasons for deciding not to, I wonder if having another child was my only chance to truly heal.

“I so wish Aidan had a sister,” I wrote in my letter this year. “Would you be the kind of sister who would want to help him build things? Or would you be mischievous and knock down every marble tower? You would have been as beautiful as Aidan. We would have loved you as much as we love him, as inconceivable as that might be. To think of loving another person on the planet that much — how our lives would have expanded, how our hearts would have expanded, how our world would have been that much more beautiful. Instead we have a hole where you should be and sadness where there should be laughter and all that love and you, whoever you would have been now, whoever you would have grown to become, our daughter, Aidan’s sister, our beautiful little strawberry blond-haired girl. Wherever you are, sweet angel, know that we love you and miss you so much. More than anything, with a longing as deep as the earth’s core, we wish you were here with us.”

Andrea Meyer’s writing has appeared in such publications as the Boston Globe, the Village Voice, Elle, Glamour and The Huffington Post. The author of the novel “Room for Love,” she also blogs about parenting at I Don’t Have Time To Write This! Andrea lives in Cambridge with her husband and son.