The mourning experience can resemble the dark side of the force from Star Wars. The dark side feeds on fear and anger. That’s what gives Darth Vader his power. My grief feeds on guilt and gives me the power to ruin any happy moment. I’d much rather be able to shoot force lightning through my fingertips.

My father died of ALS (Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis or Lou Gehrig’s Disease) on May 16, 2013. He was 63 years old and the best man in the entire world. My dad slowly watched as he lost his ability to move, to breathe, to do anything at all. The whole time his brain was still sharp. He was completely locked in.

Over the three years that he was sick I felt guilty the entire time. Guilty that I only visited on Sundays. Guilty that when I wasn’t there, I tried my best not to think about him and his illness. Guilty for not knowing how all those machines worked (and guilty for not wanting to). Guilty every time his friends would squeeze me on the shoulder and ask, “How are you doing?” Because the answer was “I’m fine,” and I wasn’t there.

I wasn’t there when he died either. I think he planned it that way. He knew that if I was there I’d ask him not to die, and with him being the best man in the entire world, he would have stayed and been miserable drawing out the inevitable.

My reaction to hearing he was gone was familiar. I had done it every Sunday for three years on my car ride home from visiting him. Huge panic attack sobs. Chattering teeth. Shaking hands. Then: numbness.

I expected the guilt to be replaced with pure grief. I expected food to lose its flavor, for colors to be dimmer, to basically be frozen in carbonite like Han Solo. I expected to be beyond consolation. And indeed, all that was there, but it’s always tinged with guilt. The grief comes in waves but the guilt is constant.

When I’m happily wrapped in my boyfriend arms and I’m feeling safe and cared for, that voice in the back of my head screams at me, reminding me that I should be feeling sad. And the guilt returns.

I’ve gone to six weddings since my father died, and I’ve had to walk out of the room for every father-daughter dance. Once outside, I feel guilty that I’m focusing on the fact that I don’t get my dad at my wedding, instead of the fact that he suffered and now he’s gone.

I know this is crazy. My dad wanted me to be happy. He wanted me to be productive, strong and silly. He wanted joy for me. So when the guilt rolls in (and oh, yes, it still does), I try to focus on memories of him showing me just how he wanted me to live.

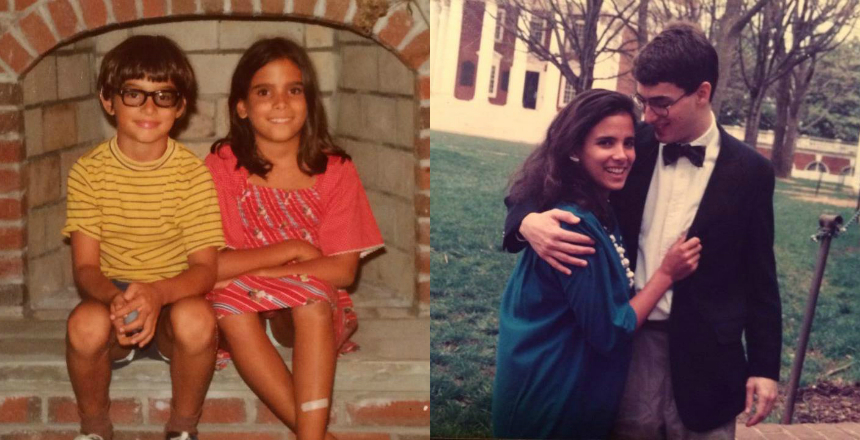

I think about him trying to cheer me up after a big break-up by telling me that I look really pretty when I’m sad. I think about him volunteering to coach my youth soccer teams year after year. I think about him attempting to help me understand my math homework. And I think about him apologizing to me when we first heard the news that he was going to die, because he knew it would be hard on me.

I’m still not sure how life will be going forward, but my dad had confidence I’d figure my way through it; in that, I take comfort.

Sara Nachlis normally doesn’t write things so serious or personal. She’s based in Los Angeles but you can follow her at her inappropriately named Twitter @FrnklinHosevelt.