The passageway of grief is lined with a thousand doors. I’ve read this description in a variety of places, not attributed to anyone in particular, but I like it. I often picture the long hallway ahead of me, light sneaking out from underneath the closed doors. In the early weeks after Mack’s sudden death I would stand in this hallway unsure of what to do. But now, I open the doors and walk in because I always find him there.

Our beloved son Mack died suddenly of sepsis on New Year’s Eve 2012, two weeks shy of his 9th birthday. Our community of soccer, church, family and friends gathered over the next few days — lifting my husband and me and our daughter and carrying us, for a time, as we all shared the horror of Mack’s abrupt death.

But those times are pauses in life when we come together to honor passages: births, graduations, weddings and death. Our loved ones come alongside us, but none of them can take on our grief any more than they can nurture a marriage for us. They must eventually go attend to their own lives, leaving us to face our agonizing new reality.

Related

“There is no question of getting beyond it,” Katherine Mansfield wrote in a 1920 letter in which she reflected on death. “The little boat enters the dark fearful gulf and our only cry is to escape – ‘put me on land again.’ But it’s useless. Nobody listens. The shadowy figure rows on. One ought to sit still and uncover one’s eyes.”

And what does it mean to sit still and uncover one’s eyes? For me, it has come to mean facing death and choosing life, sometimes several times a day. But it is not facing death as some abstract notion; it is facing Mack’s death and choosing to continue to live and love him and our family.

One of the doors I open most frequently is Room 37 in Penn State Hershey Children’s Hospital, where we arrived behind the Lifelink helicopter. The blood infection hit Mack like a bolt of lightening and overtook his kind heart in a matter of hours. His dad and I cared for his body one last time. We sat on either side of him. I swirled Mack’s wild hair through my fingers with my left hand and my right hand held my husband Christian’s hands in Mack’s, resting on his chest over his Winnie the Pooh hospital gown. We sobbed over his body until our tears dried up.

“Your baby,” Christian said to me. “Your buddy,” I said to him. And we stood up and held each other over Mack. We still do.

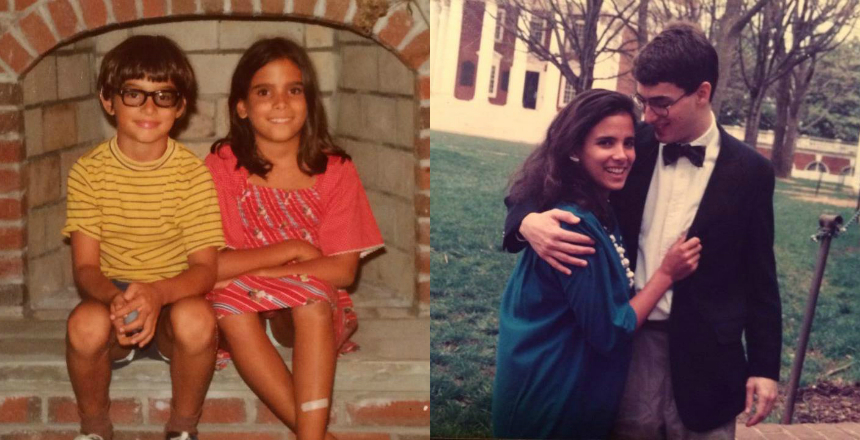

The author

It is in Room 37 that our dreams for Mack and his vibrant life, and the dreams he had for himself, were severed.

But it is also in Room 37 that I was struck silent by Mack’s repose. I dabbed my tears and drank in his face, his long, dark eyelashes at rest on his cheeks and the right corner of his mouth turned up into a slight smile. It was a smile I knew well when he was bemused. What did you see? Who came for you? I have asked him many times. His smile speaks to the beyond, to the place where I believe I will join him upon my death.

In “Hour of Gold, Hour of Lead,” Anne Morrow Lindbergh wrote that part of the process is the growth of a new relationship with the dead. It is a hidden, quiet journey within and it requires me to sit still and keep the door to my own spirit open.

I am not afraid to walk into these rooms anymore because each time I allow myself to venture in, I find Mack, whether in a dream, a memory that causes me to burst out in laughter or tears or even a nudge to buy or do something for someone he loves. I have learned to accept these moments of grace as the “flecks and nuggets of gold” in grief that Anne Lamott refers to in her book “Traveling Mercies.”

Mack’s sudden death still takes my breath away. But, by facing the truth of his death and choosing to live and love him and one another, I am able to embrace my whole life with my eyes uncovered.

Elizabeth and her family honored one of Mack’s dreams by establishing the Mack Brady Soccer Fund that helps recruit and train the best keepers for Penn State men’s soccer. She teaches at Penn State and her essays on learning to live with loss can be found at mackbrady.com and opentohope.com.