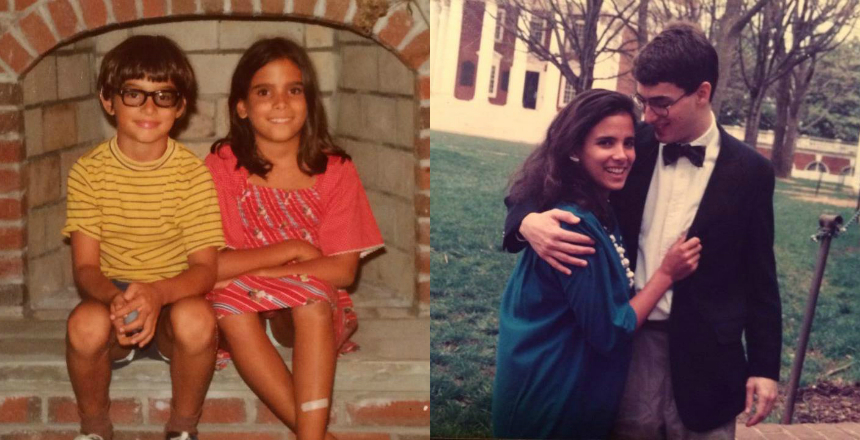

When I began writing my novel, I told my dad that it was inspired by my sister — and it was. What I didn’t tell him was that I was also planning to use him as a model for the character’s father. I didn’t tell him, probably, because I knew I was going to have to kill him off, suddenly, unexpectedly, early in the narrative, and I didn’t want him to take it the wrong way. Chances of my manuscript ever being published were slim anyway, and I knew that if it ever got to that stage, my father would relish every page, laughing at the way I’d portrayed an alternate version of him, knowing I’d written him out of love and good intention. He’d boast about it to everyone he met.

I was never expecting my father to die suddenly, unexpectedly, with my novel still in its early stages. He hadn’t been suffering from any illnesses, hadn’t battled any discernible diseases, hadn’t signaled any warning signs, and yet one day he was found unconscious, unable to be revived.

I had been out to dinner and hadn’t thought to turn up the ringer on my phone. When I finally checked the screen, I found I had 12 missed calls — all from my mother.

“Dad died,” she said, before anything else.

READ: Visiting Dad on Google Street View

After the shock, and eventually the reality, of her words hit me, guilt began to creep in. My father’s death felt so surreal that I put away the bulk of the novel for years. I picked at it now and again, but I was paralyzed by the thought that large-scale revision might further manipulate fate. I had foreseen his death in writing, down to the type of death he would have, and now that the fiction had become a reality, his passing seemed like proof of the power of my imagination, the negative impact of visualization.

Of course, the rational part of me understood that all this was absurd, but superstition is not rational. It’s about trying to control the uncontrollable, to explain the inexplicable. And it made perfect sense to me at the time. In fact, I began searching for other signs that this was my fault, and I had no trouble finding them. I looked back at the photo book I had given my father for his birthday the year before, for example, and became convinced that with that “gift,” I had sealed his fate in a hardbound book of pictures that couldn’t be amended. I had congratulated him on the end of a life he was still living.

Of course, the rational part of me understood that all this was absurd, but superstition is not rational. It’s about trying to control the uncontrollable, to explain the inexplicable. And it made perfect sense to me at the time. In fact, I began searching for other signs that this was my fault, and I had no trouble finding them. I looked back at the photo book I had given my father for his birthday the year before, for example, and became convinced that with that “gift,” I had sealed his fate in a hardbound book of pictures that couldn’t be amended. I had congratulated him on the end of a life he was still living.

The worst part was that I had done these things without recognizing the need to say goodbye.

Ultimately, I realized, it wasn’t the impression of having had a hand in his death, or even the need for closure that haunted me, so much as the notion of the missed opportunity. Those years when I worked only blocks away from his office, yet squandered his lunch invitations. When I chose not to pick up the phone, or deflected his myriad questions, his genuine interest in my life and effort to better understand it. When I allowed myself to grow annoyed by his dissection of the Yankees, his extended assessment of the situation in the Middle East, or his analysis of the Sunday morning talk shows.

READ: There’s No Good Time or Place for Bad News

I had taken him for granted, presuming I knew how he viewed the world, but I hadn’t bothered to ask him. It didn’t occur to me to seek his advice or perspective, to consider he had a point of view worth examining more closely. Now I wouldn’t have the chance to inquire about his secrets, things I thought I didn’t want to know so many years earlier: about his childhood, or the the first impressions he had of my mother, or how he felt when he held each of his children for the first time.

The more time that passed, the more acutely I realized how much more complex he was than I had given him credit for, how layered his intelligence and compassion could be, how many more questions I would’ve asked given the opening. But now it was too late. And that much, at least, was on me.

Years after his death, after finding the strength to finally complete the last page of my novel, and a home for the completed manuscript, I was anxious to receive the actual book. I hadn’t read it from start to finish for a long while, and I was anticipating all of the cringing and desire to wholly change certain elements, the compulsion writers have expressed of never feeling satisfied with a supposedly finished product. What I wasn’t expecting was all of the grief.

Looking back on the finished work, I could see that “Dad” was the one who, draft after draft, stayed most true to life. Lucy, the character inspired by my sister, continually evolved, as did the other fictional characters generated over the life of writing the story. While of course “Dad” was not entirely Dad, certain characteristics remained consistent: his corny sense of humor, his strong faith and belief in dreams. Perhaps, in the end, I hadn’t wanted to tamper with his character any more than I already had.

As I flipped through the pages, I mourned anew while reading the fictional funeral scene, and for the new recognition that my real father wouldn’t be there to see the book come into being, that he wouldn’t be present to see me read from the novel, or boast about his daughter, the published author.

And yet it was satisfying on some level to note that I could feel him again in the pages, alive in a whole new way. His speech patterns, his limping gait, his desire to protect his family. It’s not the same as watching his face light up after finishing the book for the first time, but to know that my father is preserved in the pages themselves is some kind of solace for the lingering guilt. For all of the unanswered questions, and all of the missed opportunities, I can’t help but think he would’ve been proud.

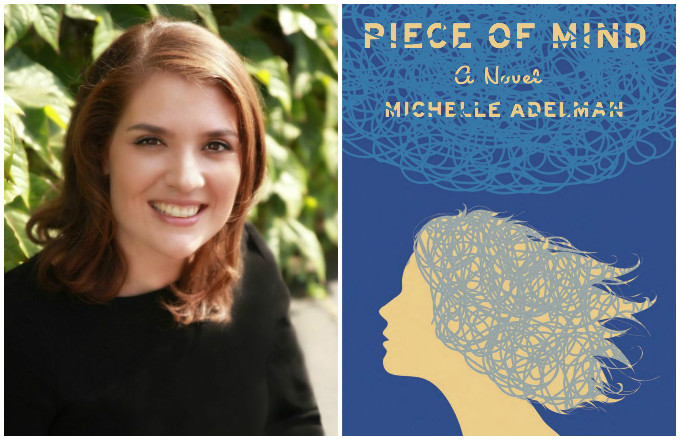

Michelle Adelman is the author of “Piece of Mind” (Norton, Feb 2016). Her writing has appeared in Bustle, Fiction Writers Review, Extract(s) and elsewhere. She lives in San Diego.