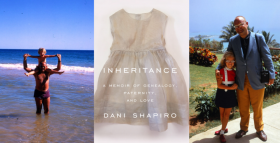

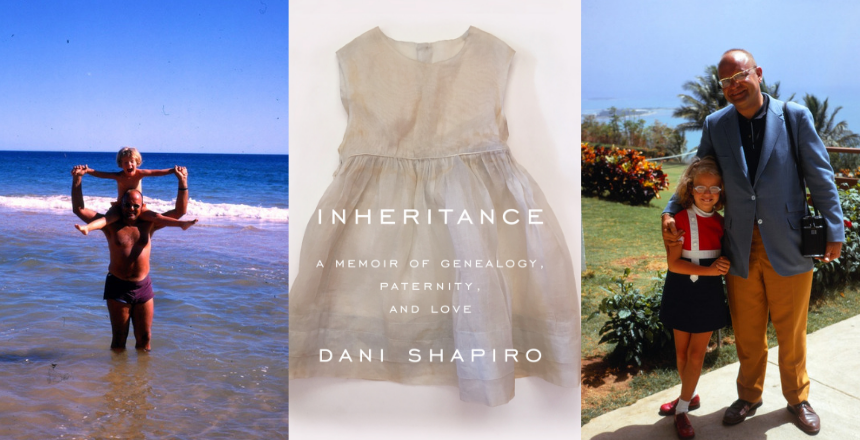

Dani and her dad at the beach, circa 1968; Inheritance; Dani and her dad, Paul Shapiro, in Portugal, circa 1972

In the spring of 2016, Dani Shapiro stumbled entirely by accident on a massive, 54-year-old family secret through a commercial DNA test. Her father, whom she adored and who died when she was young, was not, in fact, her biological one. Unsurprisingly, this stunning revelation sent her reeling. Shapiro had always possessed a clear family history stemming from been the observant Jewish home in which she was raised. In her new, much-lauded memoir, Inheritance, she goes deep into uncovering the layers of the secret of how she came to exist, which ranges from the world of reproductive medicine to the search for her biological father.

Modern Loss recently conducted a Q&A with Shapiro.

You’ve written extensively about the horrible relationship with your mother and the hole left by your father’s sudden death when you in your 20s. How has that grief changed shape now that you’ve finally uncovered some identity-changing revelations?

One of the first thoughts I wrote on an index card after making the discovery that my dad hadn’t been my biological father was: “Feels like losing him all over again.” The grief was a different sort of grief than the acute feelings surrounding the loss of my dad many years earlier — suddenly, in a car accident — when I was twenty-three. This wasn’t sharp — it was more like a sea of grief I was swimming in. Who was I if my father wasn’t my father? If my ancestors weren’t my ancestors? I grieved for a part of myself — a “before” version — a woman who thought she understood who she was, what she was made of. I understood that I was going to have to put myself together again in a whole new way. The image was of a puzzle spread out over the floor. I’d wake up each morning, as grieving people often do, and for a split second I wouldn’t remember. And then I would remember. In the nearly three years since making this discovery, though, much has changed. I understand much more why my parents were the way they were. Why my mother was so angry and hostile. Why my father was so sad and passive. They were harboring a huge secret — I was the secret — and it warped so much about our family life. Having that knowledge now makes sense of much that hadn’t made sense to me. In a way, this was the story I was always digging for as a writer, without knowing it.

The material in Inheritance provides a new ontology of experience in terms of the information it provides about your personal life. Has this made you understand or reframe your previous books in a new light — and if so, how?

To me, it’s fascinating that I have a trail of breadcrumbs, in my fiction and non-fiction, that reveals to me what I knew unconsciously. My novels all center around family secrets of one sort or another. I never stopped to question why. And my memoirs were my way of trying to understand my childhood, my family history, my parents and their own complications — and I became a serial memoirist because I was digging and digging for something elusive, something that felt, to me, just outside my grasp. I couldn’t have articulated that this was what I was doing. Writing has always been my tool of illumination, and so I was struggling mightily to illuminate this information that had been hidden from me.

Over the course of several years running Modern Loss, I’ve heard from readers who have grappled with secrets bearing both welcome and (mostly) unwelcome knowledge after a death; an unknown sibling or other relative, financial discoveries, marital infidelities. How might people reeling from such discoveries deal with them in a resilient way even though confronting the very person responsible for them is impossible?

It certainly was challenging for me that I couldn’t sit down with either of my parents and ask them why they had made the choices they did. Though I never felt that I wished I hadn’t known. I was glad to know, because there was still sense to be made of my discovery, even though the other people principal to that discovery were gone. There was exploring to do around the secret — both inner and outer exploring — which ultimately I found very healing as I tried to know what I could. So my advice would be, take ownership of what you’ve discovered. Don’t feel disempowered by the fact that the secret keeper is no longer living. There is often more to know.

Don’t feel disempowered by the fact that the secret keeper is no longer living. There is often more to know.

Modern Loss believes storytelling is a change agent that allows people to own their narratives instead of letting others craft one for them. How has publishing your own loss narratives over the course of many books been a change agent?

I believe that literature connects us — writer to reader, reader to writer. The act of crafting narratives out of the chaos of loss is a way of shaping that loss, making it coherent, giving it meaning, and reaching a hand out to readers to, in effect, say, “me too. I’ve been there too.” There is powerful healing in that.

How did the podcast come about? Are you discovering anything new about your own creative process by doing audio work?

After I finished Inheritance, I was on the phone one afternoon with a friend who had just read the manuscript, and reading the manuscript prompted her to tell me a very moving story of her own family secret. I was on the other end of the phone, and on the edge of my seat, and found myself thinking: I wish I was recording this. It was a very organic thought that then led to another thought: I wonder if there’s a podcast about family secrets. And it turned out that there wasn’t — at least not in the way I conceived of my podcast, Family Secrets, as a highly-produced conversation with each guest about the after-effects of a secret having been kept. I chose guests who had already, in some sense, processed their family secret and were able to be eloquent about how not-knowing had shaped their lives, and how, now, knowing shapes their lives moving forward. It has been an absolutely thrilling process, because there’s writing involved, and also people involved. I have a team: a sound engineer, a producer. I take deep dives with my guests. And I heard this week that the first season, which isn’t over yet, has just crossed a million downloads, so that’s thrilling too. What writer hears words like “million”?

How have readers responded in the wake of the book’s publication?

I’m still on tour for Inheritance, and have been to twenty-plus cities, with lots more to go. The events have been unlike anything I’ve ever experienced. People who have uncovered secrets of all sorts, but most often having to do with DNA discoveries, are showing up and telling their own stories — to me, to the audience, to each other. Parents who have kept these secrets from their children are showing up. Men who were anonymous donors and are now grappling with being discovered are showing up. I was just at Harvard Medical School a couple of weeks ago, speaking at the Center for Bioethics about the very complex time we find ourselves in, and the ethical implications we’re grappling with. 12 million people bought direct-to-consumer DNA kits last year. Two percent of them discover that a parent wasn’t a biological parent. That’s a hell of a lot of people out there, feeling confused, grieving, shocked, betrayed. It’s an incredible honor to be able to have a voice in this important conversation.

We are clearly living in a time when it’s becoming harder and harder to live with secrecy. Do you think there is ever any value in keeping family secrets?

Oh, gosh. Well, I think it depends. Mostly, it depends on when, in a life, a secret is revealed, because I think there are times in our lives we’re more fragile or vulnerable than others. But if I had to come down on one side or the other, I’d say that secrets are toxic. Just because something is unspoken does not mean it has no effect.

Rebecca Soffer is the co-founder of Modern Loss.

Learn more about Inheritance here.