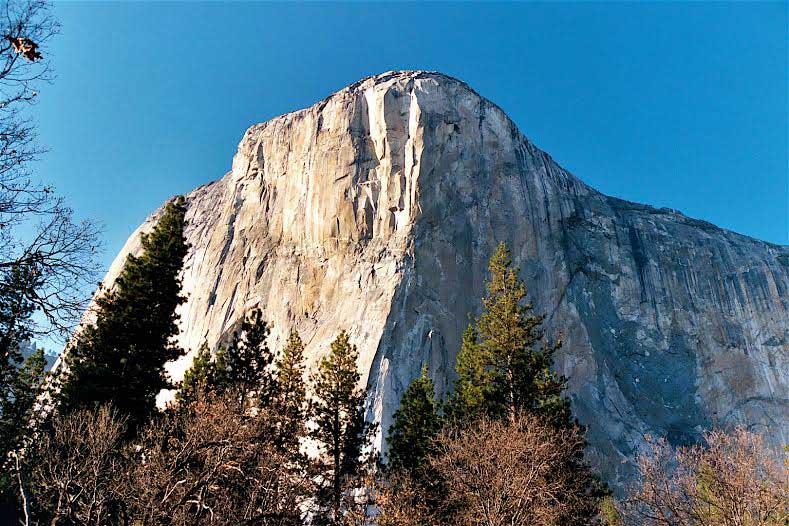

Standing at the base of El Capitan in Yosemite, I stare up at 3,000 feet of smooth, vertical stone, unable to see how anyone can climb this, but my friends will try. For the next five days they will defy gravity and death and balance on thin ridges of rock, crimp their fingers into cracks, jam their hands into gaps, and dangle under overhangs, then catch the lip of the ledge with the edge of their heel and pull themselves up.

They were climbing near where two men recently made history by “free climbing” the so-called Dawn Wall — a route so blank of holds and so physically demanding that there had never previously been a free ascent there.

My friends, by contrast, used aids; still their climb involved significant risk.

When my wife died, I, too, took significant risks because I no longer cared what happened to me. I went on 12-hour hikes through the backcountry alone — basically daring the bears, rattlesnakes and mountain lions to end my misery. I figured that if I were dead, at least I wouldn’t have to deal with this grueling grief, and I might be with Evelyn again. Even rock climbers suggested I dial my risk-taking back.

Related

At Yosemite, I like to stay in Camp 4. The climbers who congregate there are mostly in their 20s and 30s, men and women who spend evenings talking around the campfire, and drinking beer and Jack. There are about 100 climbers here this week. I’m 20 years older than many of them and a hiker — not a climber — and they’ve been nice not to point this out too often. As we tell our stories of adventure, we become friends. I admire their ability to climb into the clouds, through fatigue and mind-numbing heat, and to sleep tacked to the side of a mountain with thousands of feet of open air below them.

Yet they think they’re indestructible and that worries me. A few years ago three climbers died on El Capitan when a snowstorm swept in faster than expected and they couldn’t get off in time. Climbing involves risk, and the walking wounded in camp attest to this. Rocks break off in your hands, ropes fray on the sharp granite edges and snap, and safety gear pulls out, sending climbers falling 30 or 50 feet. But climbers need to bang their bodies against mountains. They want to learn what life is made of and they will push on every limit in order to reach the edge where enlightenment begins.

Wanting to return the favor, I caution them as they start up, “Be careful. I’d miss you if something happened.”

But what I wanted to tell each of them was this: If you die climbing that would be great, because nothing in this world will give you as much joy. Unless you fall in love, have children, and then can’t imagine anything greater than teaching your kids to climb.

Dying while doing what we love is how we’d all like to go out. But your death won’t be so great for us. As much as we joke about it, your climbing partners can’t just wipe your blood off the wall, lower your inert body to the ground, and finish the climb (although they would tap a memorial spike into the rock to mark your spot, draw your face on the granite with your tongue sticking out, and each year we’d hold a memorial climb in your honor where climbers could pat your nose as they go by).

What I wanted to say to them was that I understood the thrill of taking on a huge route, even when fear is rising in your throat, and surviving, but there’s a difference between challenge and folly. If you die doing something grand but stupid, you’re not a hero. And dying because you’re tired of living is not one of the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism. You climb to rise above suffering, not cause more of it.

I wanted to tell them that we could accept them dying if they were taking a calculated risk, because we all do that. But they train to be safe on the rock because climbing is good. It teaches discipline, teamwork, and uncorks the thrill of being alive. So don’t do any “Oh, what the hell” moves because often enough they don’t work. And if they’re thinking about doing one, think about this. Is the potential glory of pulling off one crazy move worth dying for and losing the joy they would gather from 40 more years of climbing?

I don’t know if my friends heard the unsaid in my few words, but I know how it feels to suddenly lose someone so close to you that you don’t want to go on living.

I know that accidents affect them. Earlier this week someone fell and was airlifted to the hospital by helicopter, and we didn’t know if he would survive. Many were sullen in camp: One punched a tree, and a few headed out for the hardest climb they could find to exorcise the demons. One walked to Swan Slab, a climbing wall used for training. She moved slowly up the rock testing each hold and questioning how she knew what she was doing was correct and safe. She climbed until her movements began to flow. Her smile told me that she would be okay.

Climbing mountains is life for my friends. And no one conquers fear — or sorrow — by standing at the bottom and looking up. We conquer it by confronting our fears and taking risks, even though it is hard and will take more endurance than we think we have. But grief will be our companion in the wilderness and guide us home.

Each day I will check their progress through binoculars, then go on a hike. At night I will come back and watch the tiny white dots of their head lights high on the wall, glad that they’re having the time of their lives.