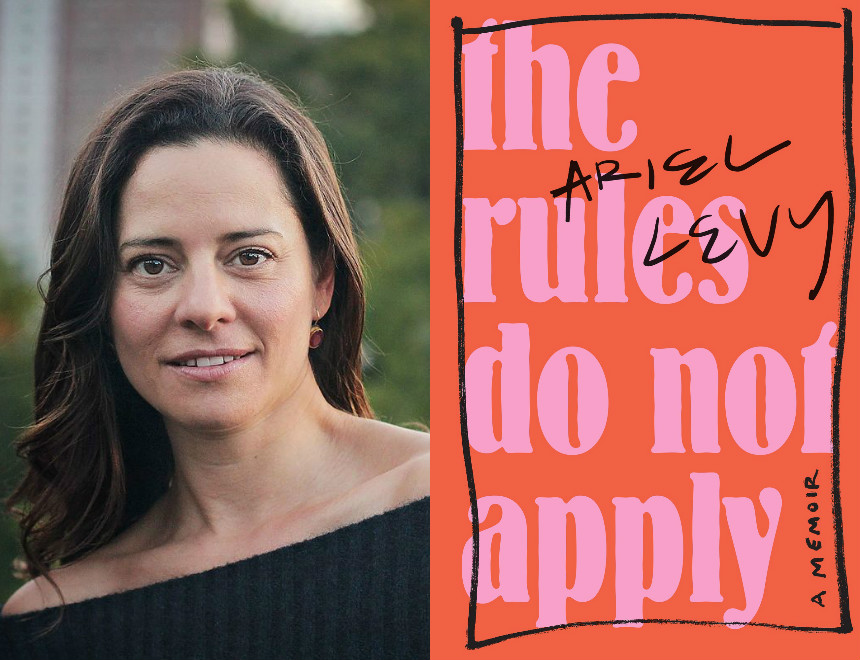

Ariel Levy, the author of “The Rules Do Not Apply” (Random House).

In 2012 the New Yorker staff writer Ariel Levy, then 19-weeks pregnant, gave birth to a baby boy on the floor of a hotel bathroom. At the time she was 6,000 miles from home, on a solo reporting assignment in Mongolia. Her son would die within minutes. Levy has chronicled her the birth, the loss and the subsequent unraveling of the life she knew in a new memoir, “The Rules Do Not Apply,” which started as a viral essay in The New Yorker. Shortly after their son’s death, Levy and her wife would divorce, and the doctor who cared for her in Mongolia would become a friend and confident, and then something more. Levy spoke recently with Modern Loss.

What compelled you to write about your loss?

I decided to publish that piece for two reasons. One, because I was proud of my my son. He was this invisible presence on earth. No one saw this creature except me. And I wanted to announce his existence. That was the selfish motive. The unselfish motive was that I thought writing about the animal experience of giving birth and losing a child, I felt this as a matter of feminism, that it was of value to publish that. There’s not that much written about this. People don’t talk about this. People don’t write about this. I still feel very self-righteous about it.

You write about taking a photo of your son, saying that if you hadn’t you might never have believed he existed. Why did you feel that you needed this proof of existence?

Anyone who has children, I’m sure they’ve spent a fair amount of time staring at their kids and just thinking, ‘god, I made you. You’re so beautiful. Look at those little fingers and eyes and toes.’ I had never made a person before. At some level I knew from the second he was born that he was not going to live and that this was all the time we were going to have together. And I knew I was going to want to stare at him again and I was going to want to show my mother. Also, everything was so surreal. I was in Mongolia. A person had come out of me. It was so much so fast. I knew I was in shock. I knew it was too much information to reckon with in real time. I knew I would want to return to it and I did.

Why did you feel compelled to show people that photo? Where is that photo now, and do you look at it still?

Once in a blue moon. But, no. That was very much the active part of my grieving. Grief is something you live in and then eventually it lives in you. When I was living in it, that was when I was looking at that picture all the time and showing people because I wanted to make real to them what was real to me.

What was the postpartum period like for you physically? You mention lactating in the book.

It was a nightmare. The hormonal letdown of birth is oceanic. Normally if you’re lucky you’re trying to keep a new person alive. That’s a pretty intense distraction. You get that hormonal letdown and that milk letdown and you’ve got no baby? It’s a bad scene.

How do you feel when people call your son’s birth a miscarriage — or relate their own stories of miscarriage — since your son was born alive? How do you name, and understand, the loss you experienced?

Right after it happened I felt this ferocious need to say he was alive. But now — it was four years ago — now I’ve got people calling it a miscarriage every time they review the book. That’s the word that people use regardless. To me it felt like I gave birth because I did.

Many [grieving] postpartum women seek out other women who’ve experienced the same thing. Did you do that?

No. Because to experience the same thing — there weren’t too many women who had given birth in their hotel room in Mongolia. It felt really specific to me. Honestly, I didn’t have the energy. I was too angry and I just didn’t have any desire to locate a community. I just wanted to stay in my bed and cry. After I published the essay “Thanksgiving in Mongolia” the year after I got back from Mongolia, women started writing to me about their experiences. I came to see that as a huge privilege. And still when I go into a reading and some poor girl raises her hand, it’s very clear to me what she’s about to say. These women have a certain look. I know I had it. Women look at me and burst into tears. They’re just blown apart. And invariably they’re going to say something about miscarriage, and I’m going to know they’ve just had one. And then all I want to do is stop the reading and hug these people. There’s a lot of hugging and crying at these readings.

“Losing so much at once disabused me of the illusion of control.”

Did what happened to you change how you feel at all about abortion?

Yes and no. I still feel every child should be a wanted child. If you look at history, banning abortion doesn’t end abortion, it just makes it brutal and dangerous for women. I am staunchly pro-choice and that’s never going to change. Do I have questions now in a different way about the soul? Yeah, I do.

People react in a variety of ways to hearing stories of loss. What were most upsetting/fucked-up things — and what were the most comforting things — people said to you in the aftermath of your son’s death (and now)?

A lot of very well meaning people said ‘you’ll have another one.’ My own father and my best friend said it. All they wanted to do was comfort me. There wasn’t a molecule of cruelty intended in saying that. But the problem with ‘you’ll have another one’ is I didn’t want another one. I wanted that one. And second, you don’t know if I’ll have another one and as it turns out, I can’t. They were wrong.

Why the desire to comfort with the assurance that there will be another baby?

When someone you love is blown apart by grief, it makes you desperate. You just want to say something to make that agony go away. The best thing anyone said, my mother just kept saying ‘you will be ok.’ And that was true. She was right. I am ok.

How has the experience changed how you relate/respond to others who are grieving?

Before this, I had never experienced grief. I have a different level of empathy for people who are in that initial all-encompassing tunnel of grief. When you lose a baby, if you’ve never lost one before the experience is so brutal, it’s easy to think, ‘is this my new life? Is this going to be my experience of existence on planet earth until the day I die?’ Sometimes when I see these women I will say it’s going to get better. I want them to know that. This is not your new reality. This will change. It’s never okay when you lose a human who you love. The worst thing about being a person is that other people die and you lose them and it’s heartbreaking. But that’s the price we pay to keep being here.

“When someone you love is blown apart by grief, it makes you desperate.”

When did it change for you?

I was actively grieving, like living in grief, for a year. There was a year of just being in an altered state. I was always just a stone’s throw away from crying my eyes out, you know? And then it became little by little more and more something that just was in me.

Was there a turning point?

I do remember one-year mark being significant. I remember thinking that Judaism had a couple of things about grieving right. First of all sitting shiva [the first week of mourning, when friends and family come to pay condolence calls]. That was a good Jewish invention. When I got back from Mongolia I liked it when my friends would come over and just be with me and eat food with me and just share the burden of grief with me. And the other thing I thought that Judaism had right was that one-year mark. In Judaism, you unveil the headstone a year later. It’s not like a year later everything is fine but it’s the end of a certain kind of mourning. I’m going to try to reenter the world in a different way now.

You describe motherhood as a place —“there is no place I would rather have seen.” So often motherhood is depicted as an oppressive identity — how did you come to think of it as a place?

That was a world I’d never seen before. If someone said, ‘you’re going to wake up tomorrow and you’re not going remember you saw Indonesia or Africa,’ I’d be like, ‘Fine. Sorry to hear that, but fine.’ The thought that you’re going to wake up tomorrow and you’re not going to remember the 10 minutes you were somebody’s mother? I would say that’s really not acceptable. I’ve never experienced anything like that and I never will again, sadly. That’s not something I’d trade. I’ll see that on my deathbed. That’s not going anywhere. That’s the most transformative experience of my life.

You connected with Dr. John over your grief, and over his, too. [At 21, he lost his brother in a motorcycle accident.] How did his seeing you and your loss up close effect how you relate to each other now?

He was the only person who had seen me as a mother with a baby who had died. That mattered a lot to me at first. And that’s one of the reasons why I fell in love with him. That guy has really suffered. That’s part of what made him who he is. And I think my experience with suffering and grief is part of what made me who I am. At this point we’ve sort of transcended that stuff. We’re talking more about the compost pile and who is going to clean the gutter.

How has your experience changed how you understand what it means to live with loss?

Losing so much at once disabused me of the illusion of control. That’s a very different way of facing the world. I feel much more open to whatever is going to happen and much less like ok, if I’m strategic and dogged enough I can mastermind my life story. That feels really different to me. That’s the upside of grief. That’s what grief gave me that I feel is of value.

Allison Yarrow is an award-winning journalist whose work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Time, Vice, Cosmopolitan, NBC News and CNN, among many other publications. She is writing a book called “90s Bitch” (Harper Perennial, 2018) that investigates myths about iconic women in the 90s, and examines the girl identity crisis of that decade. She is a National Magazine Award finalist and the author of the bestselling ebook, “The Devil of Williamsburg” (Amazon, 2013).