In 2009, when I was 22, my father took his life. It hasn’t been the only devastating loss I’ve suffered, but it has been the worst. I have felt like a black sheep among my peers and a leper in society. Few of my friends have lost parents, period, let alone to suicide. Often when I’ve told people how he died, they’ve responded with scorn or horror. As I struggled to make sense of out his senseless act, I also struggled to defend his honor. I have never experienced such fluctuating, paradoxical emotions as I have in the aftermath of this loss.

After any loss, grief manifests in a variety of ways: sadness, numbness, loneliness, disbelief, anger. But when a loved one dies by suicide — the 10th leading cause of death here in America — there is also a flood of shame: I am a bad person for letting this happen. I should have done something more to prevent this death. Francis Weller, writing in “The Wild Edge of Sorrow,” calls this “a doubling of the pain.” Buddhists call it a “second arrow.”

It’s a long, hard road, but along it I’ve discovered the following practices that have brought me some sanity and solace.

Tune Into Your Body. When Dad took his life, my body went haywire: I developed an abscess, migraines, insomnia — all of which I tried to eliminate or ignore. These were symptoms of grief, for grief is embodied — it is felt — and thus we must listen to what the body is saying.

In a moment of quiet and stillness, with eyes closed, begin to tune in: “What sensations are present in my body? How is my body expressing my grief?”

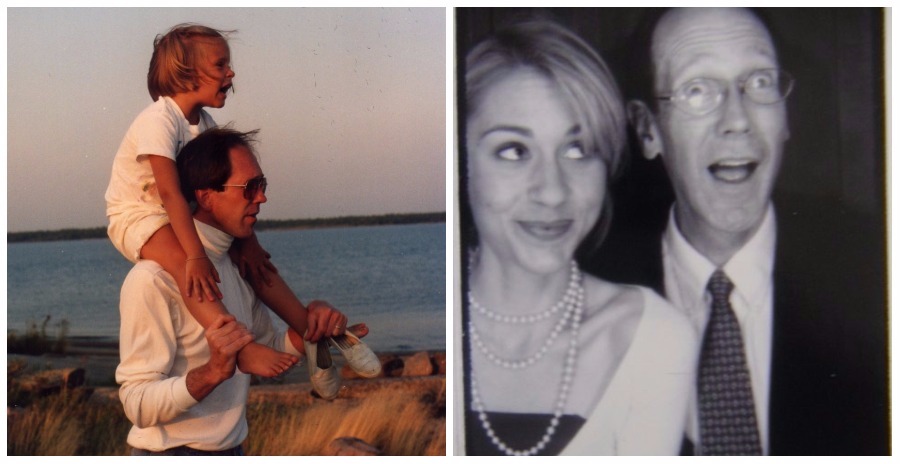

The author and her father. (Courtesy of Annie Robinson)

Welcome the Feelings. One spring day two years after Dad’s suicide, rage seized as I walked down a peaceful street. I paused, noticed it, and heard the familiar story, “I’m so angry that Dad did this, and that he’s not here…” Instead of quickly turning away from the pain, I found the courage to stay with it. In that moment, I realized that the only way out is through. When I let grief twist and turn and just exist, I more quickly find relief.

Once you notice the grief present in your body, say to yourself, “I allow myself to feel this. These sensations are safe and welcome.” Take slow, deep inhales and exhales, through your mouth and send your breath to those places in your body where you feel the pain.

Be Kind To Yourself. After Dad’s suicide, I was thrown into a shame storm and I turned on myself: “Why can’t you grieve more gracefully, like your mother and sister? You are a terrible daughter. You deserve this pain.” In therapy, I learned to offer myself compassion, to respond to vicious thoughts and emotions with curiosity instead of judgment, and to remember that I am not alone in this suffering. Others have known and are coping with this kind of grief, too. These three steps make up the practice of self-compassion.

When you notice a painful emotion arise, place your hand on your heart and gently close your eyes. Silently acknowledge its presence, and then offer yourself loving words, as you would a dear friend who was grieving: “May I be patient with this process. May I be at ease. May I treat myself with kindness.” Repeat these phrases three or more times.

READ: Narrative Practice Has Helped Me Navigate Grief. Here’s How It Could Help You, Too

Create Refuge. Dad had been missing for several days before I received the call that confirmed the worst: His body had been found, with a suicide note. I fell to the sidewalk, gasping for air. In the aftermath, I needed to recreate stability and safety, to find my footing in a shattered world. Over the following year, I made a sanctuary of my bedroom: I painted the walls, curled myself into cozy blankets and pillows, lit candles. Identifying and creating a safe place for myself allowed my body and heart to begin to mend.

Take a close look around a space you call your own (if not a whole room, perhaps a workspace, or even your car). Ask yourself, “What could I bring in to make this space feel more comforting?” Consider what soothes each of your senses: sight, smell, taste, touch, and sound.

The author’s morning ritual (Courtesy of Annie Robinson)

Foster Connection. I resisted fully showing up in relationships for several years after Dad’s suicide, as my trust in human connection was fragile. But as I began to soften that resistance and allow myself to be held by others, I found relief. Now when I notice grief swelling, I don’t withdraw from friends, I seek them out. I also find connection in literature: Mary Oliver’s poetry and memoirs about tragic loss — such as “Searching for Mercy Street” by Linda Gray Sexton and “The Pure Lover: A Memoir of Grief” by David Plante — have offered me tremendous solace. And I benefited from formal support, with trauma therapists, grief doulas, spiritual guides, and other healing professionals.

Bring to mind three people who have supported you at any point in your life. Linger on each person for several minutes, recalling a time they offered you love, help, or a lesson. Feel the warmth of their touch or their friendly smile. Notice how it feels in your body to connect with them. Express thanks for what they have given you. When you open your eyes, consider writing a letter of gratitude to each person and sharing it with them.

Practice Ritual. I found comfort and stability in the small practices of daily living: making a pot of tea upon waking, reading a poem at breakfast, walking a loop around my neighborhood. Recovering your rituals won’t happen all at once, and they will never feel exactly like they did before the suicide. And yet, we must return to our rhythms, for in patterns we find familiarity, and in familiarity we feel safe.

Choose one ritual that you enjoyed before your loss — perhaps even a ritual you delighted in as a child. Choose a time and a place that you will do it. Tell someone you trust about your intention to do it, for accountability and encouragement. Try it for one day then perhaps two, then three, and so forth. Notice if you begin to look forward to it.

If there’s one thing I can impart with the above tips, it is this: You possess the inner resources to navigate this because within you dwells a bottomless well of resilience.