Christina as a young girl, right, with her parents and sister. (Courtesy of Christina Lewis Halpern)

My father, Reginald F. Lewis, was the most successful black businessman of the 20th century. The food and beverage conglomerate he ran was the largest company in the world owned by an African-American, and 14 times bigger than its runner-up.

He died at age 50 of brain cancer. I was 12 and my sister was 19. He left behind a devastated family, a leadership vacuum at his billion-dollar business, a museum-quality art collection, a beautiful but unfinished autobiography and several walk-in closets filled with clothes.

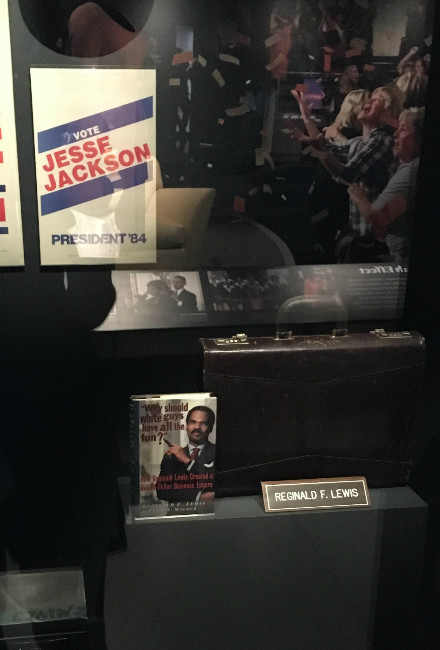

A book written by the author’s father, Reginald F. Lewis, along with some of his belongings are on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. (Courtesy of Christina Lewis Halpern)

My father had a lot of clothes: custom cashmere suits, silk ties, gold and silver cufflinks, fine wool socks, leather oxfords, leather belts, and lots of lots of bespoke Italian dress shirts, monogrammed RFL at the left midriff. For a long time after his death, it felt like we were drowning in those shirts. He had so many. Some were starched, pressed and folded in his closet. Others were hanging. And at least 20 new ones — blue ones, white ones, blue-and-white-striped ones — sat wrapped in plastic in a box, unopened, on the floor, for years.

READ: David Carr’s ‘Lasting Totem’

Twenty years later, the Smithsonian emailed us, hoping to feature my dad’s Wall Street uniform at the new National Museum of African American History & Culture, and we discovered something unsettling: the shirts had vanished. My mom reassured me that we still had plenty of them, including a “box of new ones, still in the plastic.”

I looked for them. Somewhere there was a shirt fountain, we were sure of it. Because my father’s dress shirts, and his personal effects generally, had been so numerous for so long after his death they had intruded on our lives even when we did not want them to. We scoured our homes, their attics, their basements. Sure, people lose important things all the time, but they usually remember that they’ve lost them. My mother, my sister and I, however, seemed to have a collective case of father-owned-personal-effects amnesia.

Years earlier, Mom had moved out of the apartment where she, and we, lived with my father, but she had no memory of disposing of the shirts. Early on, she had distributed some to close family and friends, but we still had had plenty. A few years later, I remember seeing my sister wearing one. I copied her, the shirts enormous on both of our frames. We folded the thick enormous cuff once, then refolded it over itself once, then folded it twice again up the arm so that it stayed.

We were never overly sentimental about these shirts — tossing the well-worn ones, and even wearing one as a smock during a painting class in college. I had meant to get a fresh one, but it never seemed urgent. There’s more — too many, in fact — where those came from, I always figured.

Until there wasn’t.

I turned to my father’s siblings, whom I knew had been given some in the early days. One of his sisters sent me her spare shirt, a worn red one, in a gauzy fabric that I can’t remember Dad ever wearing. It’s not my favorite but it’s what I have and I wear it on his birthday. And fresh in a plastic wrapping from the dry cleaner came a pristine white button-down from my father’s other sister, hand-delivered to during our annual summer reunion weekend.

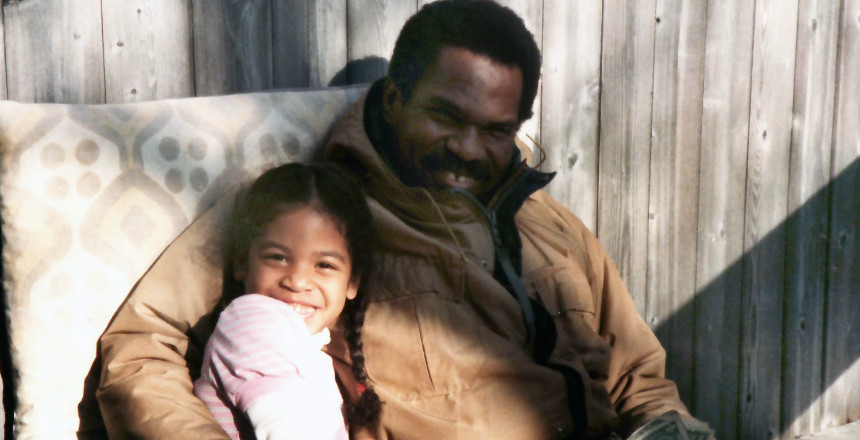

Christina and her father. (Courtesy of Christina Lewis Halpern)

I took a picture of the white button-down, and sent it to the museum curator. In addition to that shirt, the museum would be taking a copy of my father’s business card, found in the attic of our summer home; a calculator and afro pick, both from a glass display case in my mother’s new apartment; a model replica of his company’s private jet, from my mother’s office; and his scuffed, but still attractive leather briefcase, which had been on a shelf in my living room. It was missing a handle, but the monogram was still legible and the code to unlock it was still my dad’s birthday: 12-42.

READ: The Funeral Clothes Project

It’s funny. I had grabbed that old briefcase while my mother was moving and brought it to my apartment. But as the years passed I had thought about tossing it. It was big and bulky and no longer useful. Yet I had held on to it, useless as it was. And as it turned out, the museum ended up deciding the shirt was not evocative enough for permanent display. But the briefcase embodied his business acumen, ethos and style, and they enlarged their planned display case to make room for it.

Grief’s resulting haze makes it hard to see what is really there, to gain the perspective to be confident about what to get rid of and what is actually worth keeping. So don’t be in a rush. Sometimes perspective can come with time and with luck, and, sometimes, with the help of a total stranger.

Christina Lewis Halpern is the founder of All Star Code, a non-profit education organization that empowers young men to create new futures through technology. She is a 2014 White House Champion of Change and speaks frequently about technology, entrepreneurship, giving back and personal transformation. She is the author of “Lonely At The Top,” a 2012 best-selling Kindle Single memoir about her father, Reginald F. Lewis, the first African-American to own a billion-dollar business. She recommends you read it along with her father’s posthumously published autobiography, “Why Should White Guys Have All the Fun?” You can find her on Twitter @clewishalpern.