Ireland (123RF)

One thing I know about grief is that if people know yours, they’re more likely tell you theirs. While some avoid the topic vehemently or talk about frivolous things, hoping a “let’s change the subject” strategy secures a distraction, Tom and I found refuge in each other.

In the summer of 2010, five months after the death of my 23-year-old daughter, I flew to Ireland for a week-long walking retreat with the poet David Whyte, a gift from some very generous friends.

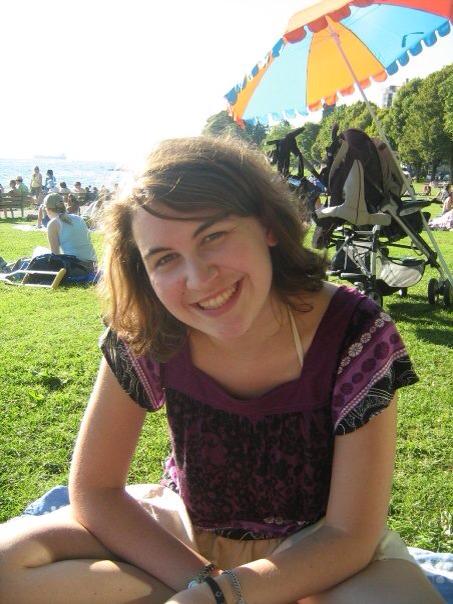

Rachel (Courtesy of Becky Livingston)

Rachel, my daughter, was an avid traveler. It was her dying wish to keep traveling. And the words of the dying carry enormous weight. But the truth was, she couldn’t actually speak. The brain tumor had taken that from her.

No, it was her father’s question.

“How about mum and I take your ashes whenever we go away?”

In the space between breaths, she nodded. Yes.

“Keep you traveling?”

Another nod.

As on many Irish summer days, the sky is a blanket of grey. The Burren, in County Clare, is a place of remembering. A grey moonscape of cracked, barren rock ribboned with crags and crevasses. A place that invites contemplation, yet demands absolute focus — one missed step and you’re down, a bleeding knee or a strained ankle. A place, I realize, where everyone I meet will only know the dead-daughter me.

Tom, another traveler on the retreat, is one of those people. Agile and mysterious like Puck in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” he’s there one second, gone the next.

Our group stops for lunch at a natural ridge protected from the earlier bleakness. A chain of shaggy brown sheep shuffles along beside us, oblivious to our presence. People huddle together and eat the sandwiches prepared for us that morning. I hold back, sit off to the side.

In my black daypack are my daughter’s ashes — not all of them, just enough to last me three weeks in Europe.

My attention is drawn toward a small rock pile. It reminds me of the balanced rock stacks common in Stanley Park in Vancouver, where I used to live. Built where land meets water, they require a sculptor’s steady hand and a calm mind. This one will surely be gone by the end of the day. The winds on the Burren are fierce.

“Can I join you?” Tom sits down beside me, places his arm firmly around my back. I rest my head on his shoulder. Atremble.

“What do you think?” he says pointing to the rock stack.

I nod.

“I made it.”

“What?” I turn to face him. “Just now?”

Yes, just now.”

He pulls out a small blue book from inside his jacket. “This is for you,” he says, placing the book in my palm. I open it to the page he’s marked. A poem titled “Rachel.” Seeing her name in print makes my heart thump.

“Incredible. Where did you get this?”

“I found it. Yesterday. My first girlfriend was called Rachel, too.”

Ireland (Courtesy of Becky Livingston)

How on Earth did he find this book? It had been late afternoon when we’d arrived in Ballyvaughan, a village with just a handful of shops. And it was just yesterday when we’d walked and talked together. When I’d told him about Rachel, he’d told me about his best friend’s daughter. “She died last year from an asthma attack. She was only 22.”

I fumble with the zipper of my daypack, Rachel’s once. But my fingers are shaking as if I’ve coerced them into a crime against humanity.

He sees me struggling. “I want to leave her ashes here,” I say.

I don’t want to cry, but I do.

“Do you need some help?” he asks.

I squeeze the sides of the cardboard pouch, the bird beak opening just enough for me to pull out the Ziploc bag. He looks ahead as I peel open the seal. Poof. I poke my hand inside, take a huge pinch of her ashes, then lean forward onto my knees and sprinkle her over the rock stack. Some of her ashes stick like a residue to my fingertips, so I wipe my hand on a tuft of grass then sit back down beside Tom.

“She always wanted to come to Ireland,” I say, as Tom pulls me in tighter and together we watch her ashes blow away.

Becky Livingston grew up in England. At 24, she moved to Vancouver, British Columbia and worked as an elementary school teacher for more than 20 years. Her memoir, “The Suitcase & the Jar: Travels With a Daughter’s Ashes” is out now from Caitlin Press. Her work appears in the anthology “Always With Me: Parents Talk About the Death of a Child.” She currently lives and writes in Nelson, British Columbia.