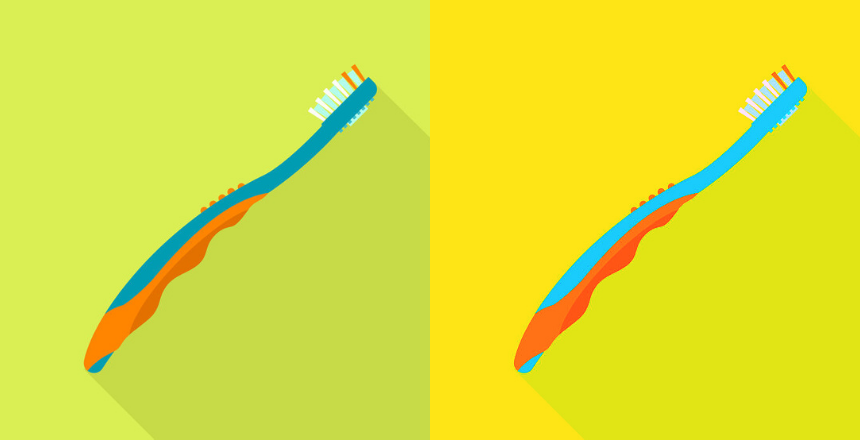

For much of her life, Caitlin convinced herself she could ward off death with homemade sacraments. Daily showers in her parents’ house became heroic life-saving missions. If the shampoo and soap bottles did not face exactly the same direction, if the bathroom towels touched each other, or were not perfectly aligned — Caitlin believed her father would die.

For much of her life, Caitlin convinced herself she could ward off death with homemade sacraments. Daily showers in her parents’ house became heroic life-saving missions. If the shampoo and soap bottles did not face exactly the same direction, if the bathroom towels touched each other, or were not perfectly aligned — Caitlin believed her father would die.

Day after day, the Kean University student methodically straightened the bathroom knick-knacks, as if everyone else’s life depended on it, all the while neglecting her own. Caitlin sometimes awoke in the middle of the night and hurried to the bedside of her sleeping parents, just to make sure they had not stopped breathing. Her shampoo bottles, she believed, would prevent catastrophe. And if not, the light switches would do the job; she flicked them on and off while repeating the words “God forbid” three times out loud. As she got older, only more rituals, like organizing pennies in precise order with all heads or tails matching, seemed to ease her anxieties.

No one helped her understand how much of this behavior might have been a symptom of a larger psychological challenge, until she enrolled in the death class taught by Dr. Norma Bowe, who had worked as a nurse in emergency rooms, intensive care, and psychiatric wards before coming to Kean University. She has taught Death in Perspective there for 15 years. She also teaches classes on mental illness, nursing, and health care. Every semester, her students take field trips to places like the cemetery, a maximum-security prison, hospice, a crematory, and an autopsy.

Over the last 10 years, the professor has developed a stockpile of writing-for-therapy exercises that she pulled out on a whim. Mid-way through Caitlin’s term in the death class, Norma had prompted students with: “If you had a rewind button, what would you go back and change?”

Caitlin went home and wrote as honestly as she could. One afternoon soon after, Norma took her seat in the circle of desks in the classroom and announced to the students that one assignment had stuck out from the rest, and she hoped that person would read it aloud.

“Caitlin,” the professor said, looking in her direction.

Her jaw dropped. She couldn’t be serious, Caitlin thought. Out of three dozen students, Norma had picked her to share? Who in this classroom, she wondered, would really care to hear about her? At first, Caitlin tried to ask the student next to her to read it for her, but Norma encouraged her to take ownership of the letter. Read it herself. Reluctantly, she did.

“It was about two weeks after my fourth birthday when I found my mom unconscious in my backyard with one sock on,” Caitlin began, her voice trembling as she felt all eyes on her. Tears blurred her vision as she blinked to make out the rest of the words on the paper. “She went into a coma. I don’t remember how long because I was so young, but I do remember everyone telling me mommy was sick. It wasn’t until I was about eight years old that I understood she did it to herself. She is a drug addict, and has been since before I was born. You might think I’d want to rewind and change the fact that I ever knew.”

She’d seen the scars on her mom’s wrists since she was little. They ran across like raised veins. But it wasn’t she got older that she’d learned her mom had slit her wrists and set her bed on fire before Caitlin was born. Caitlin eventually realized the pills were the problem. Some of the labels had weird words, like Xanax, Vicodin, and Percocet. The pills were bad. The pills might kill her mother. “She loves the pills more than she loves you,” her father would tell Caitlin, forcing her to look at her mother’s swollen, drooling face.

“I’m constantly worrying, even when there is nothing to worry about,” Caitlin told the class that day. “I stress myself out and over-do everything, like it’s going to fill some void.”

Through the class and the unique writing assignments, Norma helped Caitlin understand that she had obsessive-compulsive disorder and death anxiety. She connected her with campus counselors. The class gave Caitlin a rare opportunity to think about death historically and medically, debate it, and discuss it with her peers. Every young person in the class was trying to navigate death, and many were trying to do so meaningfully and intelligently. There was comfort in that. It offered the opportunity for the kind of reflection that many people tend to do in old age, or after receiving a terminal diagnosis.

Caitlin received an A in the class. More importantly, she has tackled her death fears and OCD. She later received her master’s degree in psychology, and is working toward her PhD in the field. She is also a working school counselor.

Happiness, as Norma tells her students, takes hard work. She says it should be approached like a series of homework assignments.

“Everyone admires her because of that,” says Caitlin. “But that is not an easy thing to do. You have to be brave to do that. And she has shown me how to be brave.”

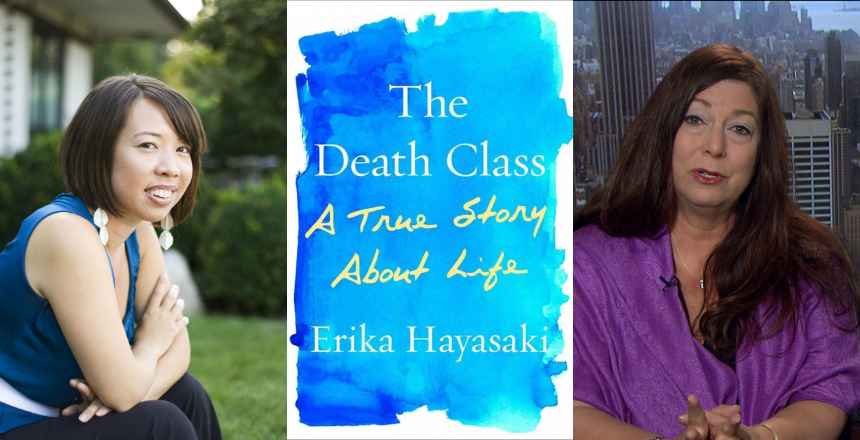

Erika Hayasaki is an assistant professor in the Literary Journalism Program at the University of California, Irvine, who writes about health and science for The Atlantic and Newsweek. Parts of this essay are adapted from her book, The Death Class: A True Story About Life, published by Simon & Schuster.