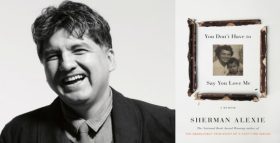

When acclaimed author Sherman Alexie posted an open letter to his Facebook page recently, explaining with heartrending candor, his decision to call off the remaining tour for his new memoir, You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me, to attend to his recently-surfaced sorrow, I felt grateful. Not because I wanted Alexie to step out of the spotlight or see his readers disappointed, but because Alexie did something so many of us are afraid to do: he exposed his personal vulnerability in a very public way and modeled what it means to give ourselves grace in the face of grief.

Though he’s written 26 books, much of the material mined from pieces of his own life – growing up on the Spokane Indian Reservation in Washington, and the ways he’s come to understand the complexities of his Native American heritage against America’s landscape – this latest book is Alexie’s first memoir. Propelled by a desire to understand, he explores the often raw, sometimes tender, deeply contradictory relationship with his mother, Lillian, who died in 2015. Alexie’s wounds have reopened on this particular writing trek, and, similar to the experiences of so many of us who have traveled the path of bringing our hardest stories to the page, the tangle of emotions that accompany those wounds has sideswiped him. He writes, “I have been sobbing many times a day during this book tour […] I have been rebreaking my heart night after night.”

Instead of slapping tape on those heart shards, slowing the internal bleeding, and donning the having-it-all-together mask, Alexie lays bare his distress. Admits he needs time away to dig beneath the surface and unearth the throbbing mass of pain he’s carrying. Needs to cradle that pain in his hands. Discover what it might be trying to tell him and eventually, us.

By giving himself permission to do this hard work and making his choice transparent, Alexie invites us to see him authentically. And, whether intentionally or not, he also challenges a culture that admires stoic resilience through grief and a literary tradition that often believes once we’ve written and packaged our stories, we’ve recovered from their damage and deposited the pain somewhere on the trail behind us.

For two years, I traveled the country to interview memoirists, who, like Alexie, had written traumatic stories. Though the journey eventually dismantled this belief for me, when I began, I hoped I’d discover that the notion of letting go the damage was true. Writing into my own story of keeping the ten-year secret of my father’s HIV disease before his death in 1995 was proving to be unexpectedly painful. I felt ill-equipped to handle the intensity of grief that materialized. If these writers assured me that grief would go away, maybe I could keep going.

They didn’t.

In interview after interview, I learned that writing about the trauma does not excise the trauma. “A rupture in your life remains a hole, a tear,” Poet Mark Doty, also author of the memoirs, Heaven’s Coast, Firebird, and Dog Years told me. Richard Hoffman, poet and author of Half the House and Love & Fury said, “You can never entirely redeem the experience. You can’t make it not hurt anymore.” And author Jessica Handler, who wrote Invisible Sisters, explained her lasting pain this way, “It doesn’t mean that a part of me isn’t on this sublevel, this sort of low hum of almost consistent freaking out.”

Talking to these writers for my book, Writing Hard Stories: Celebrated Memoirists Who Shaped Art from Trauma, and plumbing the depths of my own memories for my memoir, has instead planted in me the understanding that healing has many layers. In the transformative process of finding language and shape for our stories, we peel back some of those layers. But, as author Andre Dubus III revealed in discussing his memoir, Townie, beneath those layers are more layers. “[T]he writer [goes] to the bottom of the experience and what [does] he or she find? More bottomlessness. There are no answers, there are only questions.”

I suspect that in writing about and, as book tours demand we do, talking further about his turbulent relationship with his mother, Sherman Alexie uncovered such questions, each holding their own wells of sadness. By honoring his need to dig into that sadness, Alexie humanizes the journey and himself. He also answers a particular call of the writer: to open space where others can lean into our experiences and find courage to reveal some of their own. “I’ll still be writing,” he promises, “And I know I will have new stories to tell about my mother and her ghost. I will have more stories to tell about grief. And about forgiveness.” Alexie’s conviction to keep at his craft while tending to his wounds is grace for his readers, too. A grace that anticipates the honest work yet to come.

Melanie Brooks is a freelance writer and the author of Writing Hard Stories: Celebrated Memoirists Who Shaped Art from Trauma (Beacon Press, 2017). Her memoir-in-progress explores the lasting impact of living with the ten-year secret of her father’s HIV disease before his death in 1995. Her work has appeared in the Washington Post, LitHub, Bustle, Creative Nonfiction, Hippocampus, The Huffington Post, and other noted publications. Melanie lives in New Hampshire with her husband and two children. Connect with her at melaniebrooks.com or on Twitter @MelanieJMBrooks.