Midway through June of 1982, I was summoned from my usual post in the Connecticut bureau of The New York Times to spend two weeks doing a night shift in the legendary newsroom on West 43d Street in Manhattan.

I was 26 and less than a year into my dream job, one I had coveted since first visiting the Times on a sixth-grade class trip. I was also in the midst of some struggle, trying to rapidly raise my standards from the local newspapers of my career thus far to the rarefied echelon of the Times.

The temporary reassignment had come through my immediate superior, Jeff Schmalz, the regional news editor. Though Jeff was only a year older than me, he had worked at the Times since dropping out of Columbia and essentially ran the city desk. The title he really deserved with me was “rabbi,” newsroom slang for that kind of boss who guided and guarded you. Though many considered the night shift a punishment, Jeff saw it as a way for me to get to know more editors and them to get to know me.

As the last day of my two-week stint approached, Jeff gave me a field assignment. I would cover the Gay Pride Parade. I understood his agenda right away. Already in my brief time on the Times, he had told me he was gay, the first person in my life to make such an admission. Somehow, in spite of my overall ignorance, he’d sized me up as someone capable of being sensitized to the reality of gay existence and of doing some small part to personally improve the Times’s coverage of it.

Related

After all, these were the days when official Times style forbade using the word “gay” except as part of a direct quote. The only acceptable term otherwise was “homosexual,” so chilly and clinical and alien. I was just beginning to grasp the fear that many gay and lesbian journalists on the Times felt, a force that kept many in the closet and compelled several into paper marriages for the sake of their careers.

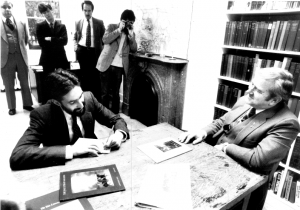

Jeff with Gov. Mario Cuomo at the 1988 Legislative Correspondents Association dinner in Albany, NY.

Jeff must have first told me he was gay during one of our periodic working lunches. Though I can’t remember the exact time and place, or the precise words he used. But, I remember his tone: calm, confident, matter-of-fact.

Nothing had prepared me for the liberating ordinariness of his disclosure. My greatest mentor, a high school English teacher named Robert W. Stevens, had been a gay man driven into alcoholism by the pressure of being closeted in our small New Jersey town. When a college classmate of mine confided to a group of friends that he had a gay brother, we took this the news with a somber hush, as if to commiserate over the diagnosis of a terminal illness. And yet I considered myself an enlightened, liberal guy.

Then, not so many years later, here was Jeff steering my path at the Times. If I had done well, then when the phone rang for me in the Connecticut bureau, Jeff would crisply say, “Hey, Scoop.” His lessons and advocacy ultimately brought me such visibility within the Times that I was plucked from Connecticut to cover the Broadway theater beat, a plum assignment. I wound up renting an apartment on the Upper West Side a few blocks from Jeff’s, so I now saw him both at work and outside the office. In our conversations, he offered me a window into a gay life that was not neither tormented nor apologetic. When we had dinner after deadline one night at a theater-district bar Jeff favored, he flirted up the host right in front of me. He talked about the gay clubs he frequented, the way the dance floor lit up when all the chorus boys showed up after their Broadway shows. He even joked about his taste in men. “Twinkies,” he explained. “Young, blond, and dumb.”

When speaking about journalism, though, Jeff could not have been more serious with me. He burned for the Times to cover gay people and issues in a way that wasn’t exotic or judgmental and knew the newsroom politics well enough to recognize that such change would not happen easily. Young, straight, sympathetic reporters like me were Jeff’s stealthy emissaries – even on a story as essentially innocuous as the 1982 Gay Pride Parade — in his campaign to have the Times view gay people as normal.

Sam Freedman interviewing Rev. Jerry Falwell during his controversial visit to Yale University. (Photo copyright 1982 by Rollin A. Riggs)

On a day-to-day basis, our paths diverged in 1987, when I left the Times to start writing books. Jeff moved from editing into reporting, rising up the ladder to become a bureau chief in Albany and then Miami.

In December 1990 Jeff collapsed in the newsroom. Soon after, I heard that he had been diagnosed with AIDS. Remarkably, in that era before drug cocktails to manage the disease, Jeff recovered enough to return to work. And during the last year of his life, he took on the AIDS beat, finding his own voice after years of enabling the voices of reporters whom he mentored.

The last time I saw Jeff was in the late fall of 1993. He lay dazed and mute in his bedroom, far gone with AIDS. On his nightstand, I saw the paperback book he’d evidently been reading, “Of Mice and Men.” Something about Steinbeck reminded me of another detail from my conversations with Jeff. For all of his Manhattan panache, the crisply pressed trousers and shirt, the impeccable navy blazer, he spoke tenderly about having grown up in a small Pennsylvania town. For recreation, his mother sometimes took him to watch the volunteer firefighters battling a blaze. Someday, Jeff told me, he wanted to write a novel about all that.

Death was Jeff’s final lesson to me. Just as he was the first openly gay man I knew, he was the first person I knew to die of AIDS. In the years since then, his absence has harrowed me. I could not separate the upward trajectory of my writing career from the ways Jeff had elevated my abilities and also negotiated my way through the labyrinth of Times newsroom politics, which had ruined people far more talented than me. For lack of a better term, I felt survivor guilt. And beyond it, I grieved that as the years passed, fewer people would remember who Jeff Schmalz was and what tremendous work he had done.

A few years ago, I had a student in my introductory reporting class at Columbia Journalism School. She was struggling mightily, not only with the lofty standards of the school but also with the culture shock of having come from a small town in southern Ohio. Finally, about halfway through the semester, she turned in an article of publishable quality, and in trying to convey my approval and infuse her with confidence, I instinctively called her “Scoop.” Eventually, I told her everything that nickname had meant to me, when I was the greenhorn and Jeff was the rabbi. To this day, I can’t quite bring myself to call that former student, by now a professional journalist on a cable network, by her given name of Kellianne.

On Pride Day of 2015, two days after the Supreme Court ruling for marriage equality, I went back to Greenwich Village, beholding a world so changed that I don’t think Jeff Schmalz, dead for nearly 22 years by now, could have dared to imagine. Yet it was precisely the world for which he prepared me.

Samuel G. Freedman is a columnist for The New York Times, the author of seven books, and a journalism professor at Columbia. Updated Nov. 30, 2015: He and Kerry Donahue have completed a radio documentary and companion book about Jeff Schmalz’s AIDS reporting, “Dying Words.”

Top image: Metro Desk in the third-floor newsroom, April 1982: William Greer, Jeffrey Schmalz, Nicholas Horrock, Charles Strum, Dennis Stern, James Gleick. Courtesy of The New York Times Company Archives (1982).

Selections from Jeff Schmalz’s reporting on AIDS:

Covering AIDS And Living It: A Reporter’s Testimony, The New York Times, Dec. 20, 1992.

Whatever Happened to AIDS?, The New York Times Magazine, Nov. 28, 1993.

On the Book-Signing Circuit with Magic Johnson; Call Him Earvin: ‘I Can’t Be Magic’, The New York Times, Nov. 19, 1992.