On New Year’s Eve 2014, I logged into Timehop for Facebook for the first time, and this is what I saw:![]()

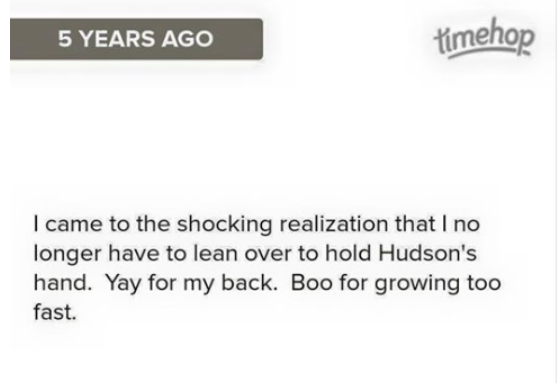

![]() 2010 did not, in fact, turn out to be an amazing year. 2010 was the year my 17-month-old daughter Hudson died from a sudden bacterial meningitis infection.

2010 did not, in fact, turn out to be an amazing year. 2010 was the year my 17-month-old daughter Hudson died from a sudden bacterial meningitis infection.

My first instinct was to tell Timehop to go fuck itself.

I had taken my time getting around to using Timehop in the first place. Many of my Facebook friends had been using it for several months, but I held back. I knew why I was hesitating. I’d seen Timehop posts from other grieving friends—photos and memories of their loved ones depicting treasured moments before anyone knew what the future would bring or poignant moments after the future had become clear but not yet final. I knew stepping into Timehop would be a bit like playing Russian roulette every day, never knowing what each new entry might reveal, unable to predict when a certain memory might trigger a new wave of intense grief.

Related

After the cruel irony of that first encounter on New Year’s Eve, I was tempted to run as far away from Timehop as possible. The fifth anniversary of Hudson’s death was approaching, along with all of its associated memories. And although those memories already run in an ever-looping slideshow in my brain, the slideshow doesn’t appear at random on my phone every morning, almost as if the events contained therein had just happened. And the slideshow is not chirpy and upbeat, complete with often-inappropriate puns and ignorant of the heartbreaking context of everything that followed.

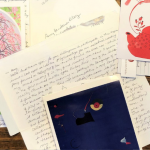

In spite of all that, I didn’t run away. Instead, I began to check each day’s Timehop entries with growing morbid curiosity. There were photos of all of the moments that seemed so ordinary before Hudson died but which seem so extraordinary now because there are so few of them—her wide grin peering out from a warm winter hood as she sledded a small hill with her dad; her grumpy expression—eyes squinted and nose scrunched—when we tried to get her to sit still for a photo among Spring tulips; her still-chubby hands trying hard to hold on to more than one Easter egg at a time. There were all my recollections of daily life with a toddler—the day I dyed her cottage cheese green for St. Patrick’s Day; the time we danced to “Mr. Roboto” in the kitchen; and inevitably (again with punishing irony), this post exactly a month before she died, about the bittersweetness of her growing up too fast:

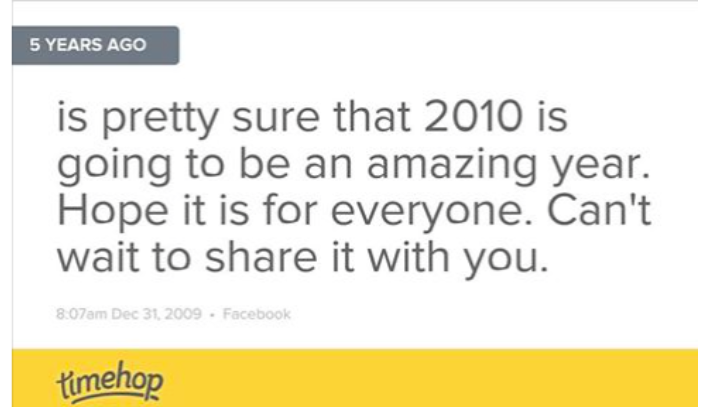

As the days trudged onward toward the fifth anniversary of her death, I found myself actually craving seeing those posts from five years ago. I’d even feel disappointed whenever I saw “No Activities” from 2010. I’ve replayed the moments from those last few weeks of Hudson’s life so many times that it seemed impossible they could feel new, but somehow Timehop brought them to life in a new way, infusing them with a sense of immediacy that they never have in that slideshow in my mind. There was a trip to Chicago a few weeks before she died that for some reason I think of as the beginning of the end. The trip home to North Carolina the weekend after that, when she had a final visit with her grandparents. The last photo we have of her, taken with my crappy Blackberry camera, as she noshed intently on black beans at a moms’ happy hour:![]()

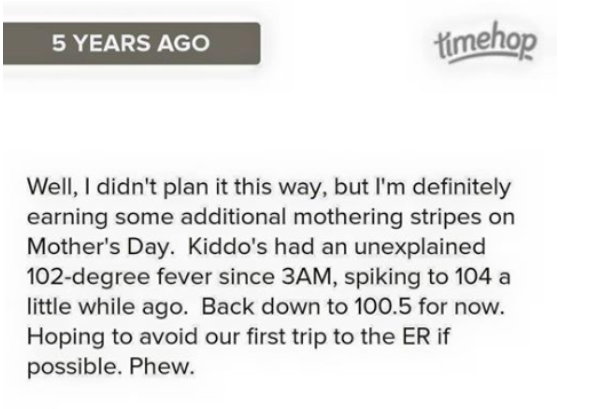

![]() Then came the first post about her illness, which came on two days later—given how sick she would become twenty-four hours later, it sounds shockingly nonchalant and naive:

Then came the first post about her illness, which came on two days later—given how sick she would become twenty-four hours later, it sounds shockingly nonchalant and naive:![]()

![]() Each of these moments flashed by me again almost as if I were seeing them for the first time. And implicit in them was a vague hope that I might actually be able to go back in time and somehow stop the silent missile speeding under cover of darkness to shatter us.

Each of these moments flashed by me again almost as if I were seeing them for the first time. And implicit in them was a vague hope that I might actually be able to go back in time and somehow stop the silent missile speeding under cover of darkness to shatter us.

But no. Timehop isn’t a time machine. No matter how many times I see that first post about her fever, the outcome never changes. My daughter is still dead.

As time insists its way forward, as our lives grow ever larger around the hole that Hudson’s death left, my grief is my most powerful connection to her. And during those months surrounding the anniversary of her death, I needed that connection more than I needed anything in the world.

Timehop isn’t a time machine but rather a time capsule. And every day when I opened the app, I welcomed not only the chance to peer into the past at my most cherished moments with my daughter, but also the chance to connect with her in that way that only my rawest grief can offer. I understand now that this is why, despite all the warnings, I deliberately plunged into Timehop in the first place.

Mandy Hitchcock is a writer and recovering lawyer whose essays have been featured in The Washington Post, The Huffington Post, The Sun Magazine’s Readers Write, and others. A mom of three—two living children and one sweet spirit—she lives with her family in Carrboro, North Carolina, where she writes away in her basement and practices just a bit of law on the side. You can follow her on Facebook and Twitter, and read more at mandyhitchcock.com.