Two and a half years ago, my dad died of lung cancer. His decline was quick and steep. I found out about his death while on a train headed to my parent’s house — to him — from New York City, where I live. While on the rush hour commuter rail, I got a call from my older sister; he was gone.

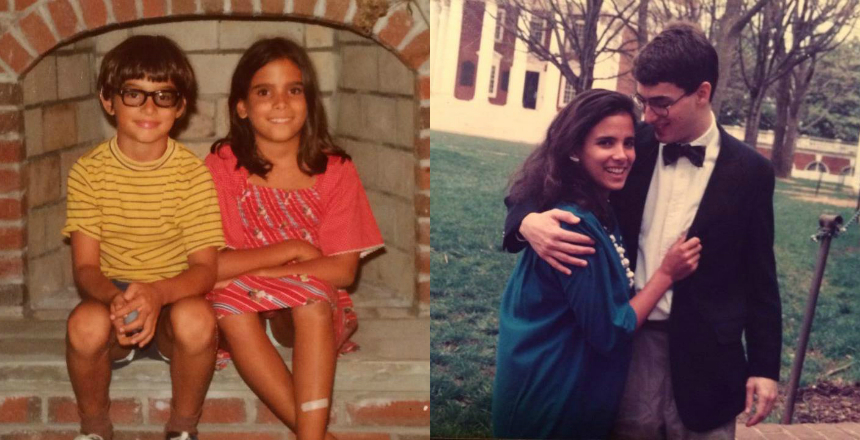

Cindy with her father

Perhaps the only good thing about learning the heartbreaking news alone on public transportation is that my mom had no idea where I was. For as long as I can remember, she has made every effort to give me a heads up when she’s about to deliver bad news, to put me in a safe place with people who love me.

Years ago, at the tail end of my junior year in college, my older brother was in a near-fatal motorcycle accident. The news came to me over the phone and the first words out of my mother’s mouth were “Where are you? Who’s there with you?” She refused to tell me any details until I was with someone who could provide comfort. My roommates were out wrapping up final exams; I was home alone writing a paper. But because it’s not hard to find a friend nearby when you’re in college, my friend Kristen was on my couch next to me within minutes. “Call your mom back,” she said. “I’m here.”

Related

Fast forward a decade, and I’m riding the Metro-North to Westchester County on that hot summer day, with a stranger sitting next to me. She could clearly tell I was going through something painful. The tears were flowing and my hurt was evident, quiet as I was trying to be. Still, this woman didn’t get up, did look up from her iPad, which she tapped with her left pointer finger, or make any attempt to see if I was okay. I wanted to scream like Veruca Salt. I wanted to hurl her iPad into the next train car. I wanted to push her off the seat. I wanted room. I wanted space.

But what I learned in that moment is this: Even with the solace of a comfy couch in a quiet living room, with fresh tissues and blankets and plenty of space, with wine nearby and someone to hug you, nothing makes that first punch of pain any less raw. Not the alcohol I don’t taste or the arms around me that I don’t feel.

Despite my mom’s many attempts to put me in the best possible place while delivering a crushing blow, in the end it doesn’t matter. If I’m hearing about my dad’s cancer diagnosis while walking along Seventh Avenue South or under my covers, it doesn’t matter. If I’m hearing about him leaving this life sitting next to an oblivious passenger on a train or in my parent’s den, it doesn’t matter. Loss is loss, pain is pain, and bad is bad news.

When I hung up with my sister, I dialed until I heard another voice. I told my best friend I was too late, that I missed saying goodbye to my dad. “Just talk to me,” I said. But hers were words that, in the moment, I didn’t hear.

Weeks after my dad died, I told my mom where I was when I heard the news about Dad’s death: alone on the train, in the company of strangers, so close to home but in the end 30 minutes too late.

“I’m so sorry,” she told me.

I looked at her and knew she didn’t just mean she was sorry I didn’t make it in time to say goodbye to my dad. She wished that I wasn’t on a train; she was sad that I wasn’t with those who loved me.

“It doesn’t matter,” I said and I believed it.

Now when I see someone walking down the city street — crying, phone in hand — I get it. When I catch a glimpse of a person slumped against a building, overcome and defeated, tears streaming, I recognize a little piece of myself. I know those tears. I’ve gotten those calls. I was one of them once, too.

Cindy Augustine is a journalist who usually writes about other people — not herself. She lives and works in New York City but travels when she can, and takes photographs everywhere she goes (yes, some are of food). See her pictures on Instagram and follow her on Twitter.