Honest, open, and expressive communication is essential for supporting a child who has experienced or become curious about death and loss—but it can be a daunting conversation to start.

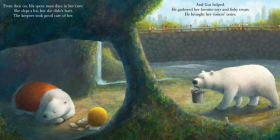

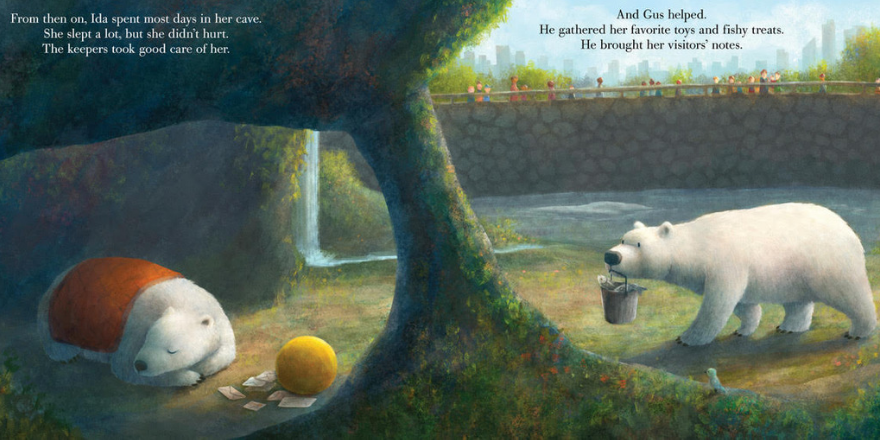

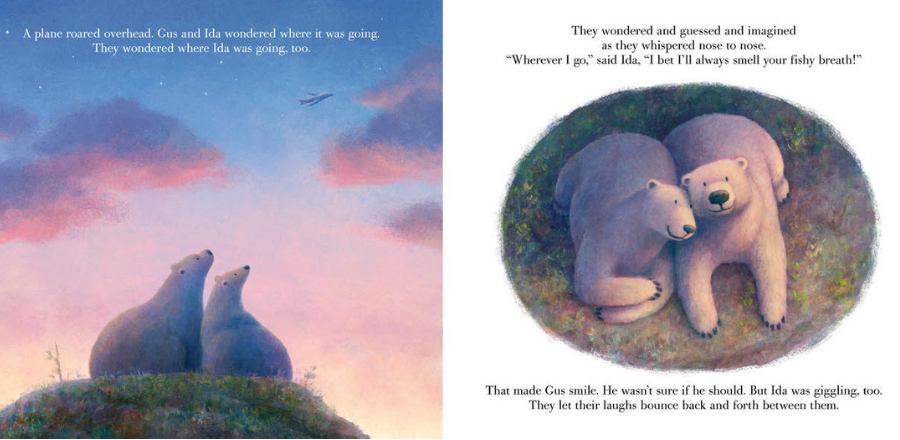

That’s why I wrote Ida, Always, a picture book about death and loss for young readers. A book is a creative and safe place to experience and explore Big Feelings and Questions together. Books helped my mom support me, when in elementary school I came to her, confused and full of feelings I couldn’t name, having heard that Charlie, my first school bus driver had gotten sick and died. Recently, when working with a student who had lost her dad and couldn’t talk about it—I wasn’t sure what to do. So, we read about the bereaved bears in my book and then she chose to write her own story about her dad. Writing a personalized story is a meaningful and enjoyable way for caregivers to engage children in this important and challenging conversation.

If you decide create your own story for a child in your life, try to embrace the process with an attitude of discovery. You don’t need to know everything or have all the answers. The most important thing is to simply be a caring guide and provide a safe space for exploration. By doing so, you’ll be able to help a child to validate, normalize, share information, and empower them to become active authors of their own experiences. Gather some paper, crayons, your sense of play, focus in on your child, and use these seven steps to go from idea to “publication”:

1. Prepare. Before starting, read some published stories on loss, engage in self-care (I mean it!) and identify support systems and resources. Always utilize professionals (school counselor, therapist, doctor) for any questions about whether your child might be experiencing trauma symptoms or needs extra support.

2. Create structure. Depending on your child’s age or needs, you can create everything alongside them or make a book to be illustrated, colored by them while you read.

3. Choose a focus. What part of the story needs to be explored? Is your child struggling to understand the concept of death? Do they need a way to celebrate the person they loved? A space for them to share worries? Here are samples of the kind of story focus you may want to consider:

- Memory book. The story of one special time or a collage of remembrances. Start each page with the prompt, “I remember…” Ask: what sights, sounds, smells, foods, places, objects, holidays, events, dialogue are associated with the person/animal? Include challenging memories along with the positive ones to allow the deceased to be fully human and give permission for complicated feelings. Example titles: Spot’s Memory Book, My Grandpa Smelled Like Cookies, I Remember My Mom.

- Preparation book. A story to prepare a child for a funeral, memorial, or upcoming change related to the loss. Use a repetitive prompt and the five senses: “When we go to ____you might see/hear/feel__.” In this story indicate what trusted adults and friends will be there. “When we go to ___people who love you will be there like ___.”

- Processing book. A story to help explore feelings around past events that might feel confusing, complicated, or even joyful like a memorial event. Example: Visiting Uncle at the Hospital, When I Found My Goldfish Upside Down, We Flew Balloons for Cousin. Here you want to allow children to let you know what they saw, felt, and still wonder about. Be sure to allow for both confusing/scary and hopeful/safe moments. Prompts can be: “When I went to the hospital/funeral/ I saw__ and I felt__.” Or “When __told me__blank had died, I felt___.” Be sure to help them spot hope and safety with prompts like, “I saw people helping by ___.” and identify hugs and other ways people comforted each other.

- Big questions/big worries book. For kids curious or worried about death and what happens after death, you can write a [Child’s Name] Book of Big Questions: and then read it and explore answers together.

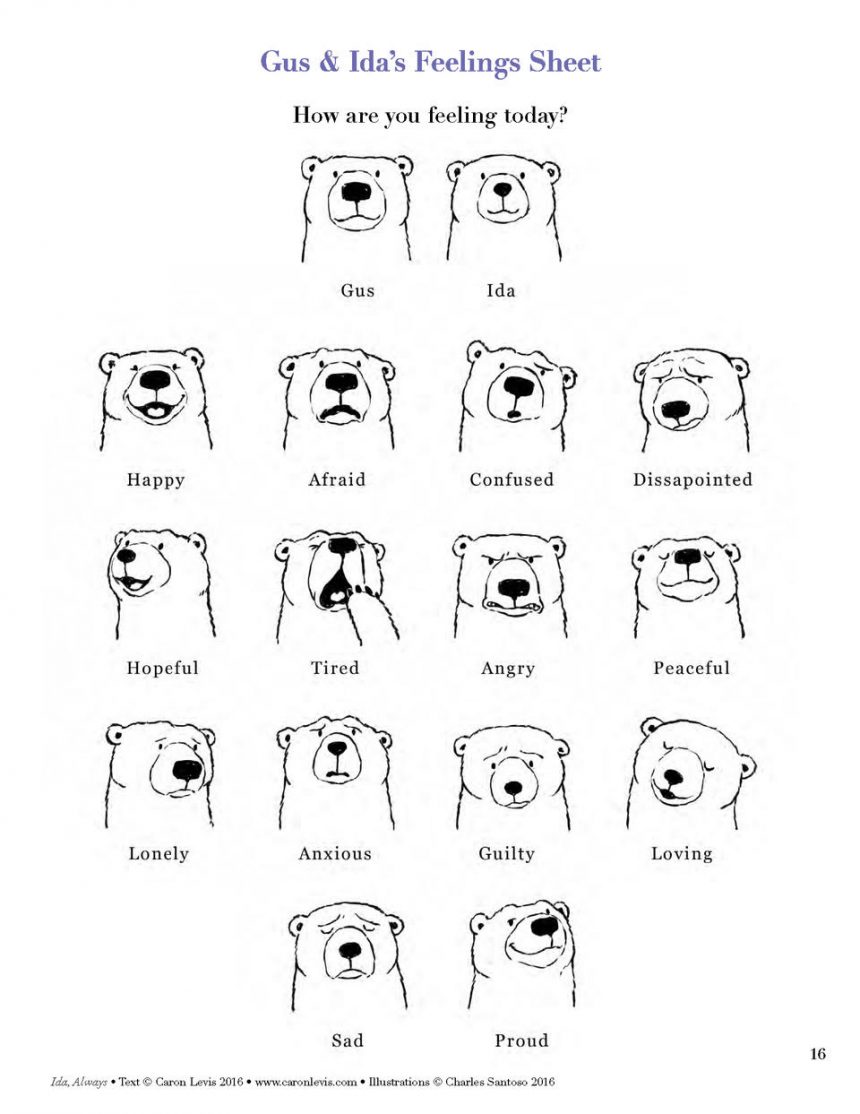

4. Discover your story’s language. Listen, reflect the child’s words, clarify with your own, and expand their loss vocabulary by sharing and defining important words.

5. Create a hopeful ending. Just as in real life we don’t want to minimize a loss with platitudes, we don’t want a book about loss to get wrapped up in false glitter and bows–so think Hopeful rather than Happy for your ending. Your story might end in a joyful dance or a partly cloudy, reflective sky; either way, hope must be present. Hope is found in nature, future adventures, memories, places/activities that make us happy, and the people who love us. Usually a kid will find it for you. While writing Ida, Always, hope came from my memory of a kindergartener telling me, “It’s good we have hearts that beat, so we can remember the people we miss.”

6. Put it together. Your book can be as simple as stapled drawing paper and crayons, or as crafty as collage, glitter glue, laminators, computer programs. Provide choices to gift your child feelings of creative control.

7. Share. Provoke pride and celebrate your accomplishment by reading aloud and/or finding a special place for the book. Follow your child’s lead. They may want to move on or want to read it again and again. They may want to keep the book for themselves and you, or share with important family members. If your child wants to bring this personal and sensitive story to school or friends, be sure to discuss and make this choice with them. While communicating about a loss is essential, so is the choice of who, when, and how much to share. Sharing the story in the right situation can promote a sense of needed connection.

8. Reflect. Ask your child how it felt to write this story together—and let them know how much it meant to you.

For more information, activity sheets, and resources on communicating about death and loss with children, refer to the free Ida, Always guide (www.caronlevis.com).

Caron Levis (MFA; LMSW) is the author of several picture books including the award winning Ida, Always about love and loss inspired by a real life polar bear friendship, which the New York Times Book Review calls, “an example of children’s books at their best.” She is the coordinator for The New School’s Writing for Children/YA MFA program and facilitates loss and bereavement groups for children with The Jewish Board.