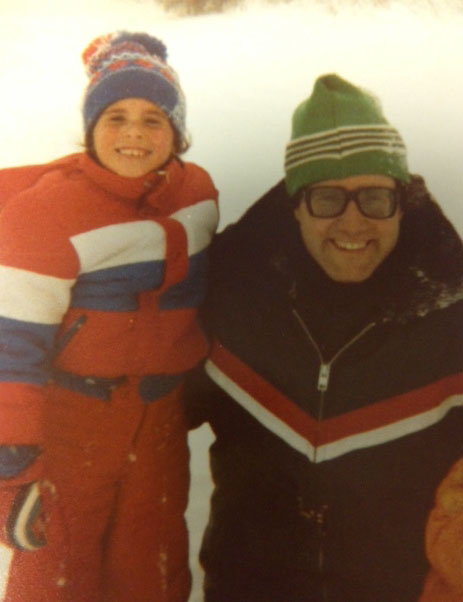

At my father’s funeral, as we stood in the frigid February weather waiting for the casket to be lowered into the ground, the rabbi rushed over to me and asked in a desperate voice: “Do you have anything to say to your father? This is your last chance!” I barely hesitated as I told him that I had no unfinished business, nothing to say. I had loved him intensely and I had known that he loved me.

I was living in Boston on the morning he died. I had been at a neighborhood Get Out The Vote meeting, the kind of thing I was just learning about as an eager new civil rights lawyer. The phone was ringing as my girlfriend, Liz, and I walked in the door to our apartment. We had been a couple for two years, and she was serving as my guide to a world I never knew existed when I was growing up. A world where affluent kids went to college at 18 and quickly established lives independent from their parents and extended families. I had commuted to McGill University from my childhood bedroom in the suburbs.

When I answered the phone, I barely noticed the panic in my cousin’s voice. He’d been calling every 10 minutes for several hours, worried that a blinking answering machine light would go unnoticed. “Go to the airport and get on the next flight to Montreal. Your dad, a heart attack, it’s serious,” he said.

I was either feeling unusually self-assured or in denial about what was going on, but I announced that I would drive the 300 miles (in Liz’s 15-year-old car, in the middle of winter) and arrive by dinner. I knew last-minute airplane tickets were ridiculously expensive. I pictured having to sheepishly ask my father for the money when the Visa bill arrived in a month.

My cousin demanded that we go to the airport now and said that someone would be sent to pick us up when we landed. Us? Liz was invited to the family emergency?

I charged the plane tickets, and two days later, Liz held my hand as we followed the coffin out the doors of the packed service. I can clearly recall fretting that any last hope I had of moving back home and marrying a nice Jewish boy was probably lost. No one was going to propose to the girl who once brought her tall, Texan girlfriend to her father’s funeral.

Liz stayed by my side throughout the foggy week of shiva and gracefully handled her crash course in Jewish mourning rituals. Still, I was relieved when she reluctantly left town to return the judicial clerkship she’d left behind. I was keeping careful score of who visited and expected my college boyfriend to be making a dramatic entrance at any moment. I had already decided that this catastrophe would mean the end of my queer and carefree life in Boston. Once the dust settled I’d surely be setting up a JDate profile and studying for the Quebec bar exam.

That week scores of my father’s old friends and longtime colleagues passed through the living room but I never thought to ask any of them this question: “Can I call you in 10 years and ask what my father would have thought of all the choices I’ve made?” Since I was planning to ditch my new life and return to the fold, I had no reason to worry about having doubts later on.

A month went by and I returned to Boston, too. I didn’t want to quit my first real legal job and my family seemed to accept that. However as the end of Liz’s clerkship drew nearer I quietly made arrangements to move back to Montreal, alone. When she asked if she could come, I insisted that she move to San Francisco, where she’d lived before law school and where we’d intended to return together. I promised that I would follow as soon as I could.

Liz must have seen the writing on the wall, but persuaded me to drive with her across the country. I’d never been on a road trip longer than five hours, but she had a knack for cajoling me into things that no one I knew had ever done before, like cooking Indian food at home or taking discarded furniture in from the street.

We visited American landmarks like Wall Drug and Seneca Falls. We drank 64 oz. sodas and listened to Shawn Colvin and boldly flirted with our female guide at Temple Square in Salt Lake City. It was exhilarating to be having any kind of fun after six months of stumbling along as a lawyer and trying to be fully in touch with my grief. When we got to San Francisco it was predictably bittersweet. We were more in love than ever and we were about to break up.

I had expected that returning to Montreal and seeing my family every day would mean that I would feel closer to my father and also less impacted by his death. But neither of those things happened. Everyone was so broken by the loss that we could barely say his name without falling apart. My mother, arguably the person who knew him best, must have resented that all anyone talked about was how perfect he was and made it impossible to reminisce about him in her presence. It was unbelievably cold, and the half-hearted JDate profile I posted went unchecked.

I realize now that the death of a beloved father is not just sad because he isn’t there at your sister’s wedding or because you didn’t get to say goodbye or because he’ll never see your new office. It’s sad — crushingly, endlessly sad — because you don’t get to know what he would think of all the choices you made, the ones you would have asked his opinion about and the ones you wouldn’t have.

You can email his friends and pester your uncles and quietly comb through the file cabinet in his study. None of it will tell you how he would feel about the fact that you moved to San Francisco a week after the year anniversary of his death. Maybe he would be impressed that you found your niche in graduate school administration and started watching baseball. Maybe he would be disappointed that you moved 3,000 miles away from every blood relative and abandoned your hometown hockey team. You won’t ever know what he thinks about the fact that despite your ambivalence, the lesbian thing stuck and your date to his funeral turned out to be the person who would give birth to his namesake seven years later.

Losing my father at 26 was the worst thing that ever happened to me, but I’ve found myself in the years since he died and I’m happy about the way things turned out. I’d still answer the rabbi’s question the same way as I did that morning in February, “No, I have nothing more to say, no unfinished business.” But in hindsight I wish I’d asked the rabbi if he could check in with me every few years and help me figure out a way to keep the conversation going.

Angie Dalfen lives in San Francisco with her partner, Liz, and their 4-year old son.