In 2011, the same year I lost my father to an AIDS-related illness, I lost my virginity to a man I barely knew. I also moved to Washington Heights, where the men appreciated my curvy body, and stumbled to find my footing both as a modern AIDS orphan and a sexually liberated young queer.

To lose my father right after college graduation made the world expand into a maelstrom of frenetic, chaotic energy. I was pushed into the world of work, the world of sex and ushered to the front of the family line in quick succession.

And sex, gay sex especially, is filled with Freudian familial language. It’s all “Spank it, daddy,” and asking whether I’ve been bad. You get called “baby.” Or, if he’s Latino, we might call each other “Papi.”

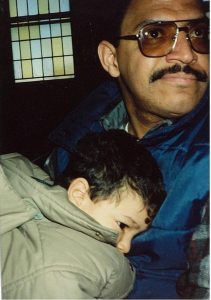

Mathew and his father.

And the first person to call me papi was my father. To be young and Latino and to be called papi is to swallow chicken soup.

Sometimes, I think about the maxim “daughters marry their fathers.” It speaks to the desire to find a man we trust, even if it’s a partner for the night. We want to feel his trust and for it to be sturdy and familiar, like a knit blanket or macaroni and cheese. Maybe daughters marry their fathers, but is this gay son dating his dad?

My relationship with my father was defined by distance, both physical and emotional. He moved to Cleveland from our home in New Jersey after he and my mother divorced in 1999. I had to learn that his love for me existed in the negative space of things we didn’t say to each other.

I know my father had interests. He loved to dance and played the güiro in a band with his brother. But, everything beyond what we needed to know about each other as father and son went untold. He never shared his HIV status with me. I never really came out to him as gay, even though I’ve been out since age 13.

With the men I date, I want to know everything about them. I want it all at once – a spiritual data dump. If something were to happen, if they were to get hit by a car on the way home from our first date, I could say “I knew him.”

My dad was a gentle, forgetful man. He’d scramble to recall facts like a child trying to capture an elusive lighting bug. In mid-October he’d ask if I needed someone to bring me out trick-or-treating that night or what Sunday in November Thanksgiving would fall on.

Related

He could cook a meal for four in thirty minutes while dancing. He would spin my mother and stir a pot of beans. He would make water soak into a grain of rice at a rate that defied physics.

In a sexual or romantic partner I seek out someone who indulges me, like my father did. My father would feed me – a little fat boy with a sweet tooth – a daily after-school snack of Oreos, and on report card day he’d give me six or seven or eight of them as a reward.

My father, like any father, wanted to teach me how to ride a bike without training wheels, to show me where to put my hands, where to fix my eyes and to anticipate when to brake. I got a black-and-blue that day. I slammed into the chain link fence across the street from our house. I don’t remember his reaction, but I know, with his help, I continued to ride. And I’d go on to have another accident, when I decided to ride the bike down the stairs of our front stoop. Once again, my dad was there to pick me up and bandage me up.

I met Ricardo*, an older HIV-positive Mexican man at an LGBT conference. He filled me up with tequila sours and we shared a sweet night in my hotel room. Ricardo did not look like my dad, but he did have a beard like his. He spoke Spanish like him. He was older like him. He had HIV like him. And, for that one night, he treated me preciously.

Ricardo was connected. He knew people from many movements and many struggles. He thrived in conversation. My father was chatty to a fault and loved human interaction. Once, my mom recalled to me, on a road trip that brought her and my father through Arizona, he met someone he knew in a desert rest stop bathroom.

Ricardo laid me down on my hotel mattress. He taught me how to touch him, where to put my hands on him and where to fix my eyes – he requested they stay locked on his as we began.

I see Ricardo in pictures at other conferences, meeting other writers, other men, other people with dads, dead or alive. I wonder if they touch each other, what they teach each other.

Even with a father around, a bike lesson can produce an inner thigh with a big purple blotch. Now – other men, other blotches, other lessons. The yearning for human connection, whether two hours or a few sweet months, is the desire to be taught, to be shown new things, to hear new stories, to get a slightly widened worldview.

My dad didn’t know me as a sexually active, dating adult stumbling through twenty-something-hood. Maybe that’s for the best. But I know he would’ve loved my willingness to crash.

Mathew Rodriguez is a queer, Latino NYC-based journalist and the community editor for TheBody.com. You can follow him on Twitter at @mathewrodriguez or contact him via his website, mathewkrodriguez.com.

*Ricardo’s name has been changed.